Major changes in higher education sometimes seem to evolve over several years before a single statistic captures the fact that a tectonic shift has occurred.

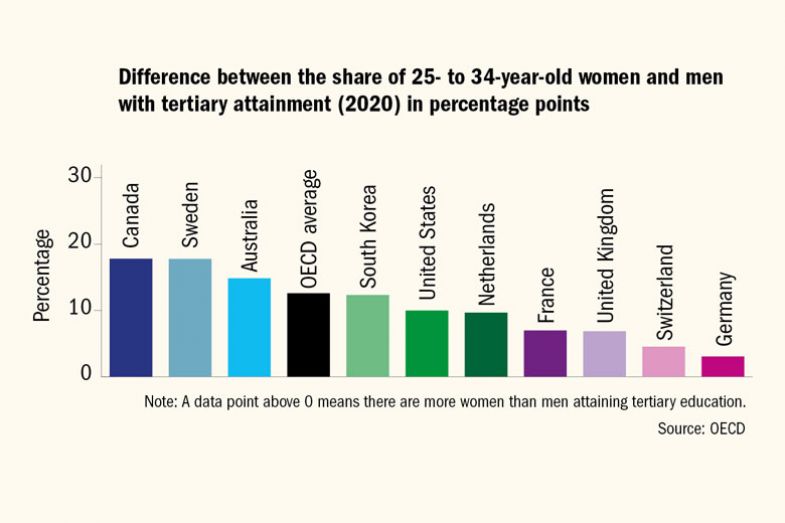

The gap in university participation between men and women is arguably one such trend. According to the huge annual dataset that is the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s Education at a Glance report, 52 per cent of women aged 25 to 34 had a tertiary qualification in 2020, compared with just 39 per cent of men, a gap that has widened by 3 percentage points since 2010. In all OECD countries and “partner” nations, except India, tertiary attainment is now higher among women of this age group.

Projections also suggest only one direction of travel: it is expected that 57 per cent of women will enter tertiary education for the first time before they turn 25 across the OECD, compared with 45 per cent of men. And while 46 per cent of women are expected to obtain a tertiary degree before the age of 30, only 31 per cent of men are expected to do the same.

Despite this widening participation gap, the OECD data also suggest that gender disparities favouring men in employment remain, most notably on pay.

“A gender gap in earnings persists across all levels of educational attainment, and a large gender gap in earnings is observed among tertiary-educated workers,” the report notes. “On average across OECD countries, tertiary-educated women working full time only earn 76 per cent of the earnings of their male peers.”

That the pay gap is worse for those with tertiary education in most countries is a sobering reminder that higher education does not seem to be a silver bullet ensuring fairness and success on other measures of gender equity.

“Increasing rates of female participation in higher education, and the widening participation gap between female and male students, have not resulted in economic or social parity,” said Kristen Renn, professor of higher, adult and lifelong education at Michigan State University.

If higher education is about “the promise of…individual social mobility”, the widening gap in participation might not be an issue, she continued, “but the inequitable life outcomes remain a problem to be examined”. In other words, as Professor Renn put it: “Why does the investment in HE not ‘pay off’ for females as it does for males?”

Experts generally agree that women struggle for equity in the workplace in terms of work-family balance, pay and promotion.

“Workplace equality is going to be key to reducing the gender pay gap. We know that part of the gender pay gap can be explained by having children. Workplaces can do more to ensure that men and women both take parental leave and are offered flexible working arrangements,” said Nikki Shure, associate professor in economics at the UCL Social Research Institute.

But as well as other factors affecting gender equity in the workplace – including evidence from her own research that “overconfidence” among men in employment also contributes to the pay gap – Dr Shure said it was important to probe the university participation data to examine what women were studying and at which institution.

“Subject choice is very important in this context,” she said. “STEM [science, technology, engineering and maths] degrees still have the highest labour market returns on average in the UK. So it is no coincidence that men are more likely to study STEM and that the gender pay gap among graduates has not decreased over time.”

Dr Shure added that research from colleagues at UCL’s Centre for Education Policy and Equalising Opportunities had shown that women were also more likely to “undermatch” on degree subjects – choosing courses with lower salary returns despite having the grades to pursue one that promises higher earnings.

“This could simply be a story about preferences, but we need to think about when and why these preferences are formed,” Dr Shure said.

“Institution also matters. My research has shown that 15-year-old girls in England are less likely to say they plan to apply to Oxbridge or a Russell Group institution than a boy at the same school with the same family background and prior attainment.”

Even if women do obtain a STEM degree, there is evidence that they may be less likely to pursue a career in these disciplines.

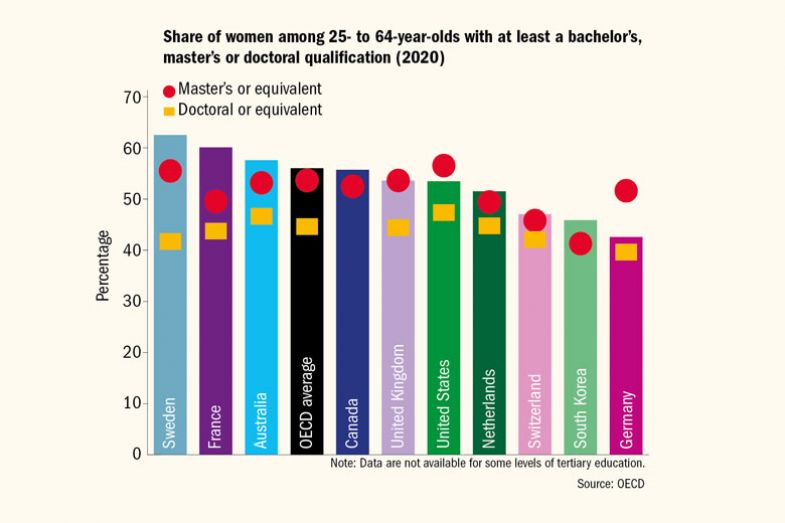

Data that neatly encapsulate this – which appear in the latest edition of Education at a Glance – are the figures for gender participation at doctoral level, a qualification more likely to be in STEM, which is skewed towards men.

Daniel Edwards, research director for tertiary education at the Australian Council for Educational Research, recently co-authored a report on why female STEM graduates in Australia were less likely to take up a career in STEM-related fields.

He said the research suggested that “establishing genuine work-integrated learning opportunities for students while at university”, such as internships or instruction from industry professionals, could help to encourage more women into STEM employment.

“In particular, these opportunities offer a way to attach to industry, build networks and establish a belonging to help in transitions to the workforce on graduation,” he said.

In launching this year’s Education at a Glance, the OECD’s director of education and skills, Andreas Schleicher, also pointed to data on women still participating in STEM at a lower rate than men.

“Women dominate tertiary education, but when you drill down and look at where they study, you still see pretty much the old pattern; it hasn’t really changed dramatically. It is something that most systems struggle with,” he said.

Evidence from the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (Pisa) initiative showed that girls aged 15 did well at science but were less likely than boys to say they would follow it as a career, Mr Schleicher said.

As a result, he was “not convinced” that initiatives in later years would encourage more girls into STEM subjects and believed the change had to come much earlier. “This is not something that we change with incentive structures later on, and that is unfortunately where most of the policy attention goes,” Mr Schleicher said.

Many experts agree that the earlier years require more attention, as it is also a crucial time for encouraging more boys, especially those from disadvantaged backgrounds, into higher education.

Anna Vignoles, director of the Leverhulme Trust and previously professor of education at the University of Cambridge, said “we certainly need to continue to focus our efforts on workplace and pay equality for women and other minority groups” because it is “a major problem in our system”.

“However, we should not ignore the fact that an increasing proportion of females go on to higher education compared to males. Tackling underachievement of low-income students, particularly boys, needs to be a focus alongside labour market reform,” she said.

According to Professor Renn, the consequences of not doing so might be most concerning when looking at higher education outcomes “related to attitudes, behaviours and beliefs” rather than the economic benefits.

“Generally, women who participate in higher levels of education marry later, have fewer children, enter the workforce and have higher civic participation than women with less education. Men with higher levels of education tend to have more egalitarian social values and higher civic participation than men with less education,” she said.

“We may begin to see some cultural conflict when more women have elevated expectations for work, family and civic life compared to the proportion of men with more egalitarian social values.”

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login