The quality of UK scholarship as rated by the Research Excellence Framework has hit a new high following reforms that required universities to submit all research-active staff to the 2021 exercise.

For the first time in the history of the UK’s national audit of research, all staff with a “significant responsibility” for research were entered for assessment – a rule change that resulted in 76,132 academics submitting at least one research output, up 46 per cent from 52,000 in 2014.

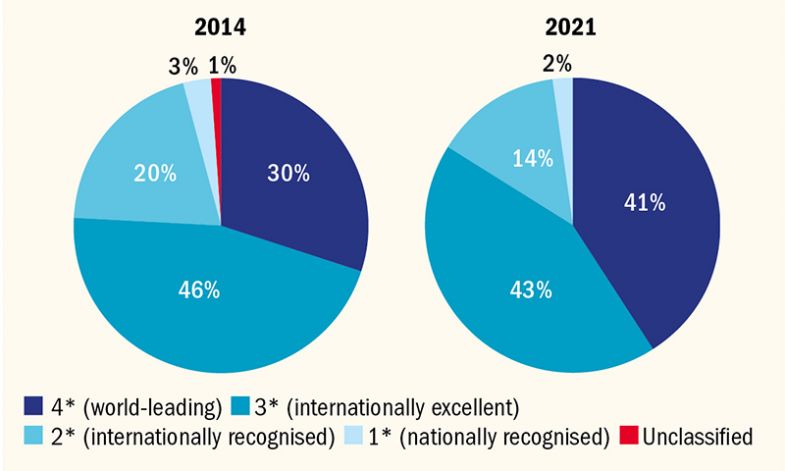

Overall, 41 per cent of outputs were deemed world-leading (4*) by assessment panels and 43 per cent judged internationally excellent (3*), which was described as an “exceptional achievement for UK university research” by Steven Hill, director of research at Research England, which runs the REF.

In the 2014 assessment 30 per cent of research got a 4* rating, with 46 per cent judged to be 3*.

Who’s up, who’s down? See how your institution performed in REF 2021

Output v impact: where is your institution strongest?

Unit of assessment tables: see who's top in your subject

More staff, more excellent research, great impacts: David Sweeney on REF 2021

Analysis of institutional performance by Times Higher Education now puts the grade point average at UK sector level at 3.16 for outputs, compared with 2.90 in 2014. Scores for research impact have also increased, from 3.24 to 3.35.

At least 15 per cent of research was considered world-leading in three-quarters of the UK’s universities.

And analysis by THE suggests that institutions outside London have improved their performance the most, with several Russell Group universities from outside the “golden triangle” of Oxford, Cambridge and London making major gains.

REF 2021 results at a glance:

See here for full results table

The results of the REF will be used to distribute quality-related research funding by the UK’s four higher education funding bodies, the value of which will stand at around £2 billion from 2022-23.

The requirement to submit all research-active staff was introduced following the review of the REF conducted by Lord Stern in 2016 and was designed to reduce institutional “game-playing” over which staff members were submitted.

Outputs in REF 2014 and 2021

The uptick in quality may be driven by universities focusing instead on which of their researchers’ outputs should be submitted, allowing greater flexibility to pick “excellent” scholarship.

In the 2014 exercise, each participating researcher was expected to submit four outputs, but this time the number of outputs can range between one and five, with an average of 2.5 per full-time equivalent researcher expected. In the 2021 exercise, a single output was submitted for 44 per cent of researchers who participated.

University staff had welcomed the new submission rules which had removed the “emotional pressure” caused by deliberations over whether they would be “in or out” of the REF – a decision that often had consequences for future promotions, said David Sweeney, executive chair of Research England. “There is no longer that same pressure on individuals,” he reflected.

Methodology: how THE calculates its REF tables

However, the rule change has been linked to universities’ decisions to move many staff on to teaching-only contracts in recent years, with the latest data showing that about 20,000 academics are employed on such terms compared with five years ago.

This change represented a welcome clarification of academics’ roles rather than “game-playing’ on behalf of institutions, insisted Mr Sweeney. “If these contracts represent the expectations of institutions and the responsibilities of academics, that is not game-playing, it is transparency,” he said.

David Price, vice-provost (research) at UCL and chair of the REF’s main panel B (physical sciences, engineering and mathematics), agreed that “the REF may have helped in resolving many contractual ambiguities. Game-playing has not been noticeable,” he said.

Dame Jessica Corner, pro vice-chancellor (research and knowledge exchange) at the University of Nottingham, said that “less focus on individuals with the partial separation of outputs from academics has been helpful”.

“That outputs can be returned by institutions where individuals worked if they move jobs has reduced, though not entirely eliminated, the academic transfer market,” she added.

James Wilsdon, Digital Science professor of research policy at the University of Sheffield, agreed. “The large-scale transfers of people between institutions that we saw in the lead-up to REF 2014 have definitely reduced, which is positive,” said Professor Wilsdon, who said that while “choices around inclusion and exclusion of individuals with ‘significant responsibility’ have been complex in some institutions – particularly less research-intensive universities – some have welcomed the clarity that this brought to different roles in terms of research, teaching and hybrid roles.”

“The game-playing, where it occurs, is often more subtle: it’s about the gradual sifting and reordering of what kinds of research, and what kinds of impact, are deemed ‘excellent’,” he explained.

Kieron Flanagan, professor of science and technology policy at the University of Manchester, questioned the extent to which REF game-playing had been eliminated.

“There is bound to have been some of this happening because habits are hard to break – people who run university research have come in a management system informed by REFs over the past 10 to 20 years – some game-playing is inevitable,” he said.

However, Jane Millar, emerita professor of social policy at the University of Bath, who chaired the social sciences REF panel, believed the Stern review reforms had “worked well”.

“We saw a great diversity in the submissions, from very small to very large, from well-established and new units,” said Professor Millar, who added that there had been “examples of world-leading and internationally excellent quality across the range”.

THE Campus: How I plan to get through REF results day

THE Campus: The good, the bad and the way forward: how UK universities should respond to REF results

THE Campus: Don’t let the REF tail wag the academic dog

Interdisciplinary research was also “well presented”, with the Stern reforms encouraging greater links between subjects, with “sub-panels whose reach stretched through to design and engineering, physical and/or biological sciences, humanities, biomechanics, and medicine”, added Professor Millar.

With an international review body examining the future of the REF, there has been some speculation that this could be its final incarnation.

But Mr Sweeney said that the REF remained an important tool in justifying the £9 billion or so in research funding given to institutions in open-ended funding that is likely to flow from the exercise.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: REF submission rules help push quality to new high

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?