European defences of academic freedom are too often based on a misunderstanding of universities’ democratic role, according to a European Commission legal expert.

Sacha Garben, professor of EU law at the College of Europe and legal officer for the commission, said that despite “a lot of lofty talking about academic freedom in EU policy documents”, the “dominant conception” was that scholarship “is not about providing a palette of arguments, but rather it is expected to provide answers”.

She said a pluralistic academia that can contradict politicians “challenges the very assumptions of what some see as the main legitimacy of the European Union in its decision-making, namely technocratic governing on the basis of sound scientific evidence”.

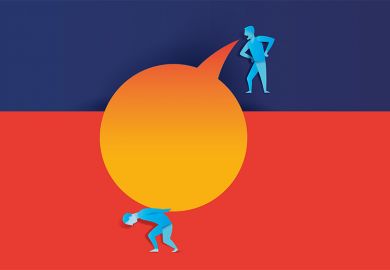

Much of EU and national policymaking is not based on universities’ “constitutional and democratic” role as a counterbalance to political and commercial interests, but on their serving a purpose that was “instrumental, vocational and promotional”, she told an event at Utrecht University.

“Universities in this conception are knowledge factories whose value for society is to produce scientific solutions to political and societal problems; to produce marketable products, innovations and patents; and to produce instantly employable entrepreneurs and professionals for the economy and for the labour market.”

Too often EU policymakers act as if universities should “pursue the objectives of the state” rather than “the pursuit of knowledge for knowledge’s sake”, she said. “Academic freedom in all this becomes very narrowly understood, mostly in its institutional relation to the state, and Hungary-bashing of course.”

Professor Garben, who worked at the Court of Justice of the European Union, said she was “offended” by the court’s “completely commercial definition” of Central European University in its 2020 ruling against the Hungarian government, which invoked World Trade Organization rules on selling services to condemn the institution’s banishment to Vienna.

To better protect academic freedom, she said European universities needed “unconditional public funding” and a “radical break with policies that meddle with curricula, especially in terms of employability”, citing programme accreditation criteria that consider graduates’ job prospects. EU policies should deter rather than encourage corporate involvement in higher education, and require transparency where this occurs, she added.

Kurt Deketelaere, professor of law at the University of Leuven, disagreed. Speaking at the same event on legal protections for academic freedom, he said that the European Research Council showed the bloc funded open-ended work that did not need to serve immediate societal, practical or commercial needs.

“If all of us would like to go back to the non-funded, ivory tower academic, there are still some universities and some countries on this globe that will allow us to do that. But I don’t think that this is the academic model of the future,” said Professor Deketelaere, who is also secretary general of the League of European Research Universities, a lobby group.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login