When Lenka Munoz’s husband had a frightening-looking mole, and the first available dermatologist appointment was nine months away, the cancer pharmacologist sought counsel from the best source imaginable.

Richard Scolyer’s revolutionary approach to cancer immunotherapy, developed with collaborator and close friend Georgina Long, had been credited with saving the lives of thousands of melanoma victims. The two, co-medical directors of Melanoma Institute Australia, have been named joint Australians of the Year.

“I was worried as my father had just passed away from prostate cancer,” Professor Munoz said. “Richard works two floors above me in the Charles Perkins Centre at the University of Sydney. I sent him an email. He immediately got back to me, and we discussed the appearance of my husband’s mole, which was later diagnosed as non-cancerous. I was thinking: ‘This guy’s amazing. He’s so busy and he still has time to discuss every lump.’”

When the tables were turned months later, she was not able to return the favour.

“I have grade four IDH wild-type glioblastoma – the worst subtype of brain cancer,” Professor Scolyer explained at a recent Sydney function. “It’s essentially incurable. No one survives. It always comes back.”

These hard facts are all too familiar to Professor Munoz, who has been studying the disease for a decade. The “amazing science done in this space” has not produced any treatment breakthroughs. “We are basically taking one step forward and two steps backwards. That’s how bad glioblastoma is.”

Professor Scolyer was travelling in the Tatra Mountains, as it happens the region where Slovakian-born Professor Munoz had learned to ski, when signs of tumour led to his diagnosis in June 2023. The standard treatment of removing as much tumour as possible, followed by intense courses of radiotherapy and chemotherapy, would give him perhaps another 14 months to live.

Detachment proved difficult for the clinician-researcher. “Knowledge is power, but what about hope? I’m also a husband. I’m a dad. I have everything to live for. I was faced with certain death,” Professor Scolyer said.

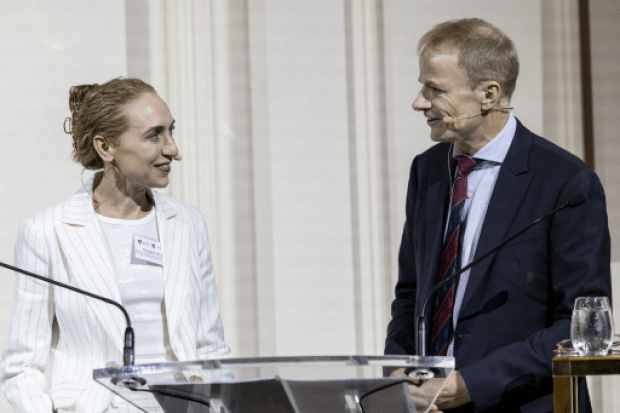

The course of action prescribed by his lifelong collaborator proved a “no-brainer”. Standing beside her friend at the function, a dinner celebrating the launch of the Sydney Biomedical Accelerator project, Professor Long said her strategy was to apply “all our learnings…to Richard’s brain cancer”.

“We are melanoma experts, and therefore we know a little bit about cancer in general. In melanoma, we have proven that it is much more effective to give immunotherapy before definitive surgery, so that the immune system is more activated against the tumour.”

Professor Scolyer’s surgery was delayed for two weeks while immunotherapy drugs were administered, allowing the immune system to train on millions of cancer cells rather than the few remaining after tumour removal. A personalised cancer vaccine was combined with the immunotherapy, in a world first for a brain cancer patient.

The approach carried many dangers. Even a short delay in surgery could allow the tumour to grow further, curtailing Professor Scolyer’s 14-month survival window. “There was understandable resistance from some in the medical community,” he acknowledged.

“Maybe I’m too much of an optimist. But our deep scientific understanding has allowed me to view my own diagnosis through a different lens. Rather than just a devastating challenge, I also see my diagnosis as a unique opportunity to progress research and treatment for another incurable cancer, like melanoma was.”

Professor Long concurred. “As scientists and researchers, it is incumbent upon us to push the medical field forward. In these moments, we…have an obligation to try something ground-breaking.”

So far, the results are encouraging. Glioblastomas often re-emerge six months after surgery, but Professor Scolyer’s scans show no signs of recurrence after nine. Laboratory tests on the removed tumour revealed a tenfold increase in immune cells, activated to attack the cancer cells with payloads of cancer-killing drugs.

“Some forward-thinking biopharmaceutical companies are starting programmes for glioblastoma, including support to perform truly neoadjuvant [before surgery] clinical trials,” Professor Long said. Such trials would be impossible without the safety data she had already supplied.

While it is still early days, the results offer new hope for Professor Scolyer and the 300,000-plus others diagnosed with brain cancer each year. “All I wish is for your approach to work, even if it means I might lose my job,” Professor Munoz half-joked in an email to him.

Scientists have a “long history” of being their own subjects, Professor Scolyer said. Marie and Pierre Curie routinely exposed themselves to radiation. “What we’re doing may not be as extreme…but hopefully, the scientific learnings we’ll generate will be just as profound. I’m patient zero for applying melanoma science to the treatment of glioblastoma.”

He told his audience he was “ambitious” for the Sydney Biomedical Accelerator, currently a construction site near the Charles Perkins Centre. Its aim is to host multidisciplinary teams of fundamental researchers and clinicians in the first complex of its type in Australia.

“We’re not curing as many cancers as we could, and it’s time the cancer research field – indeed, all medical research – gets big and gets courageous,” he said. “I didn’t have time to be scared, and neither do you.”

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login