“For she wolde wepe, if that she saugh a mous / Caught in a trappe, if it were deed or bledde.”

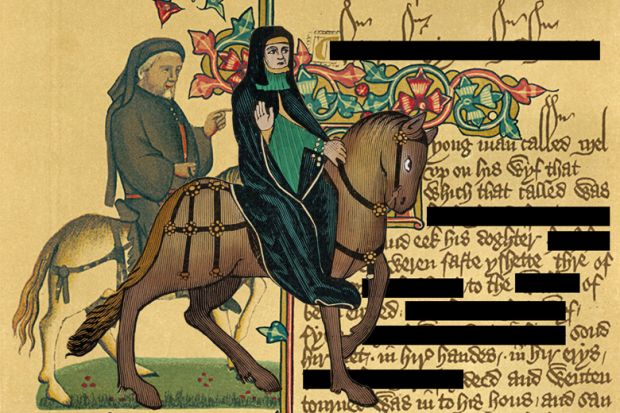

Yes, Chaucer’s prioress, Madame Eglantine, would weep over a trapped mouse – but then she goes on to recite the standard medieval blood libel about Jews murdering Christian children. And lately, it seems, such selective sensitivities are in abundance.

Just last month, the University of Nottingham was reported to have offered a course titled “Chaucer and His Contemporaries” with a trigger warning, but the warning was not about antisemitism. It was to alert students that in medieval literature they might stumble upon incidents “of violence, mental illness and expressions of Christian faith”.

Universities started issuing trigger warnings more than a decade ago, in light of their duty of care towards their students. This duty certainly includes sensible steps such as ensuring that campus grounds and facilities are safe, yet now universities are also expected to safeguard students’ emotional welfare. While this is a valid concern, academics have been bickering ever since about where to draw the line between educational challenges and sociological microaggressions.

The backlashes were predictable, yet even the critics fretted mostly about the warning’s reference to Christianity. Frank Furedi, emeritus professor of sociology at the University of Kent, argued that cautioning students who study Chaucer “about Christian expressions of faith is weird. Since all characters in the stories are immersed in a Christian experience there is bound to be a lot of expressions of faith. The problem is not would-be student readers of Chaucer but virtue-signalling, ignorant academics.”

The Christian Institute quoted Adrian Hilton, honorary research fellow at the University of Buckingham, who pointed out that Christian themes “of mercy, sin, salvation and forgiveness” pervade Western literature, so it was strange “to slap one or two [courses] with a trigger warning”. And of course, right on cue, the Daily Mail accused the university of sparking a “woke row”.

What is frustrating about these retorts is that they sleepwalk into the trap that the trigger warnings themselves have set. The university assumes that some episodes in the history of Christianity may disturb some students. These angry rebels then remind us that Christianity underpins Western history, as if the problem sparked by the trigger warning was about how we ought to adjudicate the role of Christianity in Western culture.

In other words, both sides missed the point. According to the Mail, a university spokesman said that the warning “champions diversity” and added: “Even…practising Christians will find aspects of the late-medieval worldview...alienating and strange.” No doubt. In fact, I once thought that the whole point of courses on topics as different as, say, social history, pre-modern art and literature or cultural anthropology was to acquaint students with societies that are alienating and strange.

To trigger-warn or not to trigger-warn: that is the question

Trigger warnings have been invented by academics who rightly insist that we need to think critically about Western culture, questioning our values and abandoning our comfort zones. Yet Nottingham was not apologising for a peripheral problem in medieval literature. It was apologising for exposing students to a worldview potentially different from their own – an endeavour that is supposed to be one of the essential aims of the humanities and social sciences.

We could easily dismiss the kerfuffle in this case as a trifle. After all, no one was fired, or censored, or cancelled. Yet my concern is about the wave these trigger warnings are riding. Why are academics now policing what Chaucer thinks? Because they are policing what their colleagues and students think. Trigger warnings are a symptom of contemporary universities’ sense of themselves not as places where the most pressing problems of social justice are debated – trans rights or Israel-Palestine being only two among many examples – but where such debates are conspicuously avoided, replaced by repetitively one-sided rallies and campaigns.

There is something strangely colonial about comfort zones: they swiftly become populated by people who insist that it is the rest of us who need to flee our familiar and comfortable ethical positions. It is fine to question the moral authority of the Western canon, but only against the yardstick of handpicked contemporary values. And this pretension to challenge inherited assumptions turns out to be, like Chaucer’s prioress, curiously selective about which ideas do and do not need to be questioned.

Admittedly, all members of any academic community must be concerned about historical portrayals of violence, mental illness and, indeed, Christianity. But trigger warnings’ masquerades of ethical universality turn out to be nothing but tribal slogans, trumpeting some forms of injustice while conveniently bypassing others.

I should emphasise that I am incriminating only Madame Eglantine’s antisemitism, not Chaucer’s. As with Shakespeare’s Christians in The Merchant of Venice, biases expressed by Chaucer’s characters cannot be projected on to the poet himself. Writers like Chaucer and Shakespeare must not be assumed to share the ideas that they lend to their characters. Both authors present palettes of figures whose views, taken together, are mutually irreconcilable and add up to no unified worldview at all. This is another reason to study such writers.

By contrast, what trigger warnings so parochially teach us is that writers like Shakespeare and Chaucer lack sufficient insight into their own societies – and therefore need the help of more enlightened modern minds.

Eric Heinze is professor of law and humanities at Queen Mary University of London.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?