It is probably a fair reflection of the passing of time, the arrival of parenthood and the occasional strains of a busy working life (with plenty of international travel) that I am no longer asked to prove my age when I buy a bottle of cooking wine at the local supermarket.

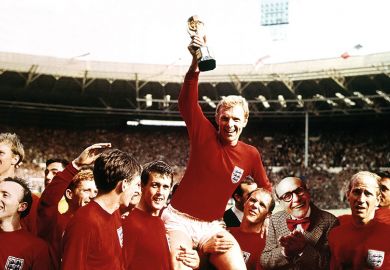

Reader, do not be fooled by the picture that you see on the left side of this page – I am not as young as I was.

I mention this not because I am unduly concerned, but because when I was appointed editor of Times Higher Education six years ago, I was regularly accused of being too young for the job by people startled by my unfurrowed brow.

It wasn’t just the individuals who blurted out the thought – there were plenty more whose assumptions made clear what they were thinking.

I have a trusty assistant who is some years my senior. He even has a beard. On occasions, when out and about with him, people meeting the THE editor and his assistant would often address David rather than me. It’s worth adding at this point that I am well aware that others will be far more familiar with such presumptions than I am as a pale male.

Where is this going, I hear you cry? Well, this is the sort of thing that can easily feed the hungry beast that is impostor syndrome: that nagging feeling that you may have reached whatever status you have reached through some fluke or mistake. That you are not, in fact, up to the job, and that this will very soon be revealed.

That academia is particularly prone to such feelings seems to be self-evident – it is not blessed with job security, and this practical instability is mirrored in other aspects of the profession, including the importance of scholarly reputation and the prevalence of self-reflection and criticism.

It is a profession in which performance is scrutinised through metrics that many feel do not fairly reflect their efforts or achievements; in which funding has to be won through fierce competition and a drawn-out, sometimes opaque process; and in which workloads seem to many to be unmanageable and ever expanding.

Even if you strip out the various other roles that scholars must fulfil, research itself is an open-ended endeavour in which there is always more to be done.

Throw in the growing sense that academics do not enjoy the public respect that they once did, and it is not hard to see how impostor syndrome could be taking a stronger grip on corduroyed lapels.

In our cover story this week, we delve into this hidden epidemic – if that’s what it is – asking six scholars to bravely bare their souls and share their own experiences of self-doubt. That they hail from five countries and a range of disciplines underlines the point that what many people feel is a personal battle is, in fact, an experience widely shared. This may be some comfort at least.

Impostor syndrome is, of course, something that students can also fall victim to and it’s worth reflecting on its role in the current crisis over well-being and students’ mental health.

As we have reported previously, delusions of inadequacy can be particularly acute for first-generation students, or those with a social background that makes them feel out of place.

Whether students or academics, the idea that university is an environment that is more suited to certain types has proved hard to shake, even if it is another suppressed thought – an unconscious bias, to use the trendy terminology.

It was a point made by Jessica Collett, an associate professor of sociology at the University of Notre Dame who researches the phenomenon of impostor syndrome.

Speaking to THE in 2016, she explained that “given unconscious biases that certain groups are more intelligent, people who don’t fit those characteristics might also hold the assumption that they’re likely lacking in that innate intelligence”.

It isn’t true, but that doesn’t stop it affecting people’s day-to-day reality. Which is why the willingness of our writers this week to share their own doubts and dark moments is such a valuable contribution. All are more than worthy of their place on the cover of this week’s THE.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Still feeling like a fraud?

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?