Pedagogy. It basically means teaching: “the art, occupation, or practice of teaching”, to be precise, according to the Oxford English Dictionary. I’ve been doing it for more than 11 years now. So, why have I come to dread that word?

Academic faculty talk to each other about our teaching with mixed feelings. It is clear to us that teaching is not the main reason we entered academia; we did that because of the research freedom we thought it would give us. We power through the teaching terms, looking forward to the months after we complete our marking, when we can hopefully find a little time to follow our passions.

Nonetheless, each of us finds certain components of teaching that we enjoy: particular topics we feel passionate about, certain ideas we feel we convey in a unique way and, of course, those rare occasions when a student approaches us after class and asks us a question that does not have anything to do with the final exam. Furthermore, most of us, myself included, do put a significant amount of time and effort into making our teaching good. It is not an aspect of our job we treat as an afterthought; we even take a certain amount of pride in it.

Nor do we have a problem with there being those whose field of research and study is education itself. Like any other academic field, it can be of great intellectual appeal. It can also be useful, shining light on teaching issues that are relevant to us.

What we do have a problem with is when those who study education as an academic field – be it as their primary field of research or as a complement to their primary research field – begin to impose their views on all academic faculty.

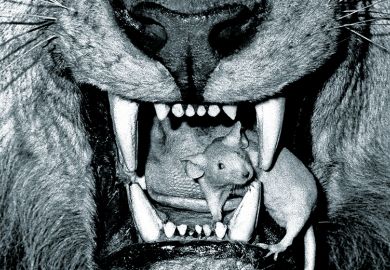

This is where pedagogy comes in. When that highbrow term is used, I know that the person talking to me is going to speak of teaching not merely from the point of view of a colleague offering advice based on their own experience. I know I’m about to be subjected to the holier-than-thou approach of someone ready to espouse the newest teaching fads as if they were the gospel truth, often with complete disregard for the specifics of my own field.

I know that such an expert is going to tell me how my course’s web page should be structured. I know that they are going to tell me what balance between lecturing and class activities I should have in my courses. I know they are going to cite studies supporting their beliefs regarding how teaching should be carried out, without engaging in any real debate about the weaknesses and biases of these studies (of which there are usually many).

And I know, worst of all, that such an expert is going to offer their advice to directors of learning and teaching across the university, directors who are desperate for any method of “improving the student experience”, delirious at the prospect of better national student survey rankings and higher rankings.

Such directors are always quick to adopt such advice, as they have been sadly quick to adopt other measures of so-called “quality control” in teaching and assessment (which ultimately guarantee no quality at all). They are happy to ignore the vast differences between academic fields, oblivious to the dangers of implementing blanket policies even within a single discipline, let alone across an entire college or university.

Am I saying that I have nothing to learn from those who study pedagogy? Of course not. I write, in fact, as someone considered by my colleagues to put a significant amount of time and effort into my teaching. But the way that the experts peddle their frequently flawed advice is not progressive, it is dictatorial.

Furthermore, academics’ time is stretched far too thinly to begin with. Our research students often don’t get the time they deserve from us. We do research during our vacations. And I can’t count the number of times I’ve seen yet another article on academic burnout.

So, dear education experts in universities, please remember: you may view yourselves as akin to Messiahs, blessing us benighted heathens with the revelatory truths of your new religions. You may think that if we would just drop everything and undertake complete bottom-to-top redesign of our courses, our students would learn more and have greater satisfaction. But remember that we can’t just drop our responsibilities for research and administration; we have contracts to fulfil.

Before you work our departmental heads up into a frenzy of evangelical zeal to transform our all-wrong teaching, please remember that you may be overestimating how much you know about how my field is taught – and how it can or should be taught.

And bear this in mind, too: once you utter the p-word, or any of its similarly pretentious relatives, most of your audience has already reached a conclusion that our experience has taught us to be statistically correct: there is no common ground between us.

The author is an academic at a UK university.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Pedagogy’s ever-shifting gospel has nothing to teach working lecturers

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login