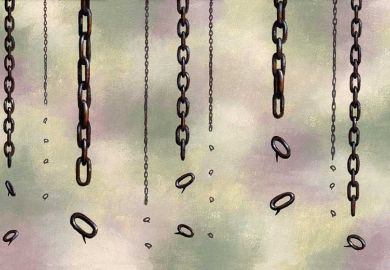

Several leading US universities have sought to make amends for the nation’s history of slavery and atone for profit they reaped from it.

That trend is now beginning on the other side of the Atlantic, with the University of Glasgow becoming the first UK institution to announce a restorative justice programme, worth £20 million ($24.5 million), for its past links to the slave trade.

Yet, for the most part, despite honourable intentions, university responses on the broad topic of racial reparations appear to have raised controversy as much as they have addressed real underlying needs.

For my research on racial redress, I’ve spent the past 10 years visiting local communities to listen to those affected by slavery’s legacy, many of them elderly, to try to understand what they regard as the meaning of real racial justice.

I’ve been especially focused of late on the Georgetown University 272 – the 272 men, women and children that the Washington-based university has now acknowledged selling as slaves in 1838 to help keep the institution financially viable (the number has since been expanded to at least 313).

The Georgetown Memory Project has so far identified more than 8,600 descendants of those slaves, and the university agreed to steps that include giving favourable admissions advantages to any of the descendants who apply to attend the Jesuit-run institution, where annual tuition fees exceed $54,000.

That promise, however, has been met with scepticism. Critics point out that generations of economic hardship have left few of those descendants educationally or financially qualified to benefit from such an offer, whatever bursary or fee discount is offered.

In my face-to-face discussions with many of these descendants, I’ve clearly heard that concern. Even among those who might qualify for Georgetown, there is unease about attending an institution far from their homes that once enslaved their family members.

But, as these descendants are making clear, that doesn’t mean either Georgetown or US higher education more broadly should not be a key part of the solution.

Rather, Georgetown and the many other US universities with similar histories should consider steps that include creating high-quality schools, such as the renowned Georgetown Preparatory School, in the cities and towns where such descendants now live.

That would do far more to lift entire communities out of the burden that slavery still imposes on them than admitting a handful of descendants to a single religiously founded university more than a thousand miles away.

If Georgetown isn’t willing to finance a preparatory school in a place like Louisiana, some descendants said, the university might create programmes in existing schools to help students prepare for college.

Other members of slavery-affected communities suggest universities work to improve US history instruction, in areas that include eliminating dehumanising portrayals of slaves, ending the idea that African-American history is different from American history and teaching the many extraordinary contributions of black Americans.

Currently across the US, responses to suggestions of reparations too often fall well short of any meaningful change. In states such as Alabama, Arkansas, Connecticut, Florida, Maryland, New Jersey, North Carolina and Virginia, legislatures have done little more than enact statements of regret for the nation’s slaveholding past. Such phrasing is often seen as avoiding legal culpability.

The lack of preserved historical records and the absence of surnames prior to emancipation are also cited as practical barriers to large-scale reparations. Since the 1990s, there have been greater efforts at a local level to address historical racial injustices. This has had some success in tackling persistent injustices in legal and policy areas.

Yet, when reparation monies are allocated, they are often tightly prescribed. One example is the $2.1 million scholarship created in 1994 for descendants of the 1923 massacre in Rosewood, Florida, which included a strict limitation on eligibility to state-approved institutions.

Notable efforts at the post-secondary level in the US include the Universities Studying Slavery commission created by the University of Virginia in 2013. The commission now has some 50 institutional members. It grew out of a 2006 report by Brown University looking at the critical role of slavery in creating US higher education.

Georgetown University’s reconciliation effort, begun in 2016, remains a unique advance in genealogical research in that many of its slaves and their descendants have now been identified by name.

A working group, established by Georgetown, acknowledged the university’s financial benefit from the sale of the slaves, about $3.3 million in current dollars, and recommended a public apology and the renaming of two buildings to commemorate significant slave contributions.

Other recommendations included continued engagement with descendants and support of genealogical research, admissions preferences and a commitment to diversity in research.

The university followed through on several of the suggestions. And in April, Georgetown students voted to impose a $27.20 per semester fee on themselves to aid under-represented communities. But the board has yet to decide on this policy and the institution still faces criticism over the practical aspects and ultimate value of the admissions preferences.

One important lesson for universities such as Georgetown is to listen more carefully to the affected communities before deciding on responses. Georgetown and the Society of Jesuits are in a great position to offer the types of accessible education solutions that the descendants are seeking. Imagine the healing of race relations that could occur if that work is done in a full partnership.

Linda J. Mann is a researcher for Columbia University’s Institute for the Study of Human Rights and founder of Justice and Equity Solutions, LLC.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?