Productive new research about conception

Sponsored by

Sponsored by

Alfaisal University is offering new insights into the successes and failure of fertility treatments

Modern medicine is accredited with seemingly countless discoveries and state-of-the-art, life-saving treatments. But even now, the fundamental practice of human conception is one that manages to leave scientists puzzled.

However, pioneering research is under way at Alfaisal University in Saudi Arabia to improve medical understanding of infertility – a complex umbrella of issues affecting as many as one in seven couples attempting to have a child.

It is a subject that Junaid Kashir, assistant professor of clinical embryology at the university’s medical school, feels passionately about. One of his particular areas of research relates to a process called “oocyte activation”, whereby calcium is released during fertilisation.

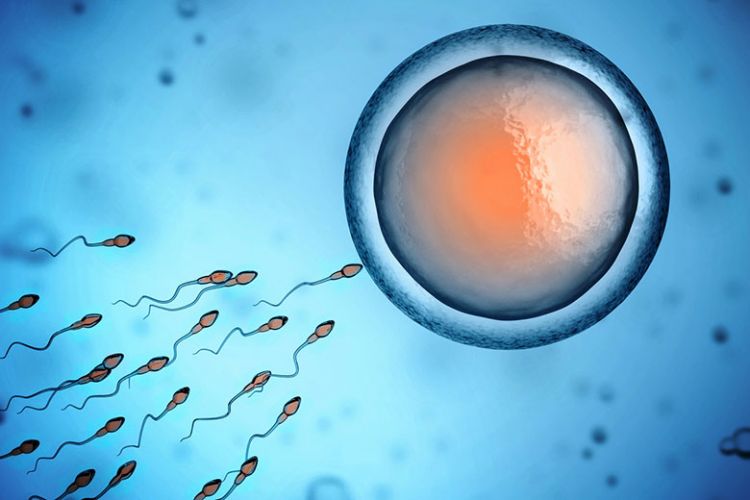

“The best analogy that I can use to explain it is imagine you are starting a car – the sperm is the key and the egg is the car,” he explains. “The process that I study is often quite literally referred to ‘the spark of life’, as it kickstarts everything.”

It is through this work that Dr Kashir came to be offered a five-year fellowship at Cardiff University in the UK. His project on “developing novel fertility treatments and diagnostics”, externally funded by Health Care Research Wales, was worth $500,000 (£386,000) over five years, with additional funding provided by Saudi Arabia’s National Science, Technology and Innovation Plan to the sum of 2 million Saudi riyal (£400,000) over three years.

Dr Kashir seeks to investigate fertility outcomes during in vitro procedures, and his research was among the first to establish the impact of mutations and defects in a particular protein on forms of male infertility.

Human sperm contains more than 1,760 proteins, each of which is thought to have a potential impact on male fertility. One of the sperm proteins that Dr Kashir studies, PLCzeta, “causes a big release of calcium”, he explains. “What’s amazing about it is it’s not just any random pattern – it's more like a code that determines not only the relative success but also the quality of embryo development, and every single animal that we’ve studied has its own unique code.”

Educated in the UK, Dr Kashir became interested in embryonic and fertility research while studying for his PhD at the University of Oxford. Now, much of what he does is driven by a desire to improve the success rate of expensive in vitro fertilisation (IVF) procedures and contribute to a more ethical industry overall.

“It’s a very evocative subject and even though it garners a lot of public interest, it’s also one of those areas that is difficult to fund,” he says. “It’s not a priority in many countries – which is really bizarre, especially if you consider that a lot of what we do as a species is for the sake of reproduction and passing on our genes.”

Part of the reason why Dr Kashir’s work on sperm proteins has gained so much interest – including from big funders – is because of its fresh approach to the potential success of IVF treatments. “IVF is not very successful, if you look at the numbers,” he explains. Since the mid-1980s, the practice has become widely applied across the world, with about 8 million babies born in 2018 as a direct result of IVF and associated technology.

“But what these numbers don’t tell you,” says Dr Kashir, “is that in the best-case scenario, one round of IVF in terms of successful pregnancies only has between a 25 and 30 per cent chance of success. So there’s a lot of room for improvement.”

Babies are big business: according to the research firm Data Bridge, the fertility industry was estimated to be worth $25 billion (£19.5 billion) in 2019, rising to a forecasted $41 billion (£32 billion) by 2026.

But Dr Kashir feels a personal responsibility to improve the success rates of IVF treatments for public health programmes in particular.

“You have a lot of private clinics who offer these really expensive methods and techniques that really offer no benefit or help to the couples,” he says. “And because couples are so desperate they will try anything, and pay huge sums of money as well.”

Some of the studies that researchers at Alfaisal have conducted suggest correlations between levels of sperm PLCzeta and the rate of pregnancy success following fertility treatment, which could be revolutionary in terms of how scientists approach IVF going forward. “Essentially what we’re finding is that calcium release at fertilisation determines a heck of a lot more than just fertilisation success,” he explains. “Imagine an intricate stack of dominoes – if the initial tip is too much or too little, something’s going to go wrong further down the line. But now we know this, we can really progress in making assisted reproduction technologies more effective.”

A key factor in Dr Kashir’s decision to base his research at Alfaisal is the level of academic freedom that he and his fellow researchers are granted, he says. For example, he was part of a team in charge of establishing a master’s programme in clinical embryology and reproductive biology – the first and only programme of its kind in the Gulf region. The course is run in conjunction with the university’s neighbouring King Faisal Specialist Hospital and Research Centre, where Dr Kashir is also an adjunct scientist.

There is still much work to be done in order to improve the quality of IVF treatment – and this requires busting some myths surrounding gender and success rates, says Dr Kashir. “In much of the world, it is still regarded that the majority of fertility problems are down to female factors, whereas that is absolutely untrue,” he explains. “It’s down to educators to make the case for funding this subject. But improving the effectiveness of fertility treatment is also in part down to addressing false myths.”

In his view, Saudi Arabia’s shift towards a knowledge-based economy provides unprecedented opportunities for researchers who want to explore pioneering research practices. “Alfaisal is at the cusp of potentially huge change. The only way to go is to keep expanding our excellent research portfolio,” he says.

Learn more about Alfaisal University.