Assessment and feedback as an active dialogue between tutors and students

Seven steps towards enhancing assessment and feedback as a participatory, social process that supports deeper learning, by Neil Lent, Tina Harrison and Sabine Rolle

Assessment and feedback are often treated as separate from learning and can turn into an annoying but unavoidable chore: students must produce the work, staff have to assess it and give feedback. Feedback becomes a commodity, a “thing”, often written information on an assignment cover sheet that is, or isn’t, read by the student.

This may work for summative judgements (assessment of learning), but it’s not so good for helping students learn from their assessments (assessment for learning). Assessment should allow students to practise working within disciplines and professions as an integral part of the learning process (assessment as learning). It should be built into the course design with regular feedback points to help students reflect. Feedback influences students’ learning, but bad feedback can be worse than no feedback.

- THE Campus spotlight: Designing assessments to support deeper learning

- Recommendations for incorporating and guiding peer assessment in the classroom or online

- The potential of artificial intelligence in assessment feedback

So how do we deliver effective, fit-for-purpose feedback?

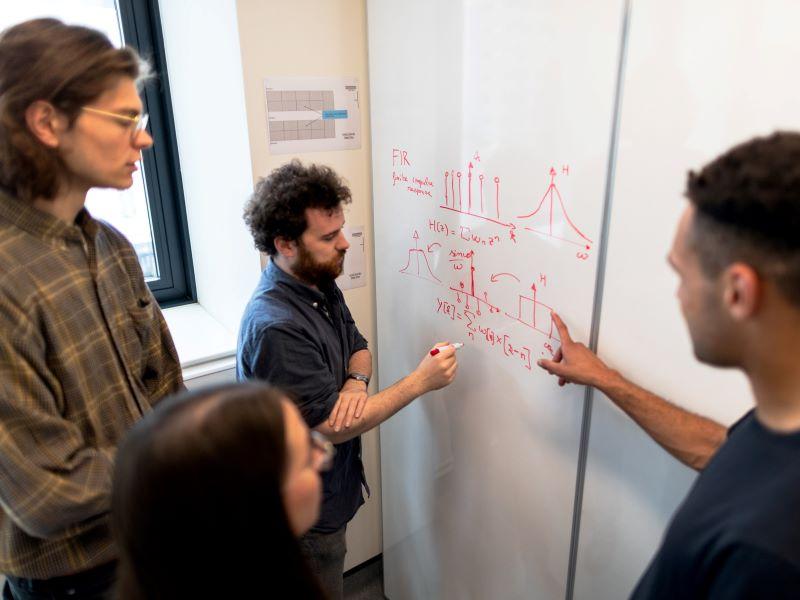

It should be an active dialogue between tutors and students by which students learn to gauge the quality of their work and become reflective learners who can evaluate their own assignments. An integrated, embedded approach to programme design where assessment and feedback is a participatory, social process is likely to be most effective.

Here are seven pointers to promote assessment and feedback for learning.

- Assessment and feedback should be embedded in course and programme design as part of a holistic approach to learning. We need to consider the role and purpose of assessment and feedback within the overall aims of a programme and its constituent modules. Assessment tasks should be varied and as “authentic” as possible, associated with students applying their knowledge by doing rather than learning about the discipline: what does a biologist, economist, historian, linguist etc, do? How can we reflect this in our assessment design?

- We should not overwhelm our students with summative assessments: less is probably more. The primary goal is learning, not measurement, and it may not be necessary to formally assess all learning objectives. Especially if similar outcomes are part of multiple courses throughout a programme. This is important as too much assessment – particularly if summative – can channel students into a pragmatic approach to work that precludes deep engagement with study in favour of learning for tests.

- Feedback should give students something to do. Traditionally, feedback tells students what they did well and where they went wrong, but there is only limited opportunity to act on this. Students need to know what they need to do to close gaps between their current level of performance and where they want to get to. Specific suggestions help them do this better than relatively vague instructions such as “tighten up your argument”. And there need to be opportunities for students to apply what they’ve learned from the feedback.

- Timing of feedback is important. Make sure feedback can be used by students in either improving the assignment assessed or in future assessment tasks. Feedback can then become part of assessment for learning. This is often termed “feed-forward” to emphasise its future use value.

- Feedback is not (just) a commodity, it is also a process. It’s not just the information the markers provide. This process should be a dialogue: between students and teachers and peer-to-peer interaction between students. This interaction should be based on ongoing, pedagogical relationships: dialogue shouldn’t only happen at “feedback time”. It can be informal and part of ongoing professional and disciplinary conversations. It can come from anywhere, at any time. This active process helps students develop feedback literacy.

- Ultimately, students create their own feedback. Students develop their own understanding and judgement of good work within their discipline. This can be achieved through self- and peer feedback using their own work and that of others. This should be included in assessment criteria.

- Good-quality assessment and feedback doesn’t necessarily mean more work. It’s about carefully considering the place and function of assessment and feedback in the learning process and designing opportunities for students to become self-reflective learners and practitioners. By involving students more in the process, through dialogic feedback and self- and peer assessment, we help them understand the purpose of assessment as part of the learning process, make feedback more useful, and foster meaningful interactions. This is more valuable than writing long comments on feedback sheets.

The aim should be to design assessment as part of the learning process. Feedback needs to be an interactive, social process in which students develop their own judgements. This will happen best with a holistic module and programme design that integrates and aligns desired learning outcomes, learning and teaching, assessment and feedback. We need to develop a culture and practice that promotes learning through interaction, where feedback is all around and can come from anyone at any time.

Neil Lent is a lecturer in university learning and teaching in the Institute for Academic Development; Tina Harrison is assistant principal for academic standards and quality assurance and a professor of financial services marketing and consumption; and Sabine Rolle is chair of student learning (interdisciplinary education), dean of education and co-director of education (UG) at the Edinburgh Futures Institute, all at the University of Edinburgh.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.

Additional Links

Read more on the topic of assessment and feedback from Neil Lent and Tina Harrison on the University of Edinburgh Teaching Matters blog, “Feedback: From one-way information to an active dialogic process”.