Teaching international students about academic integrity

Cultural misunderstandings can lead to international students being referred for academic misconduct. An answer for university educators can be to tailor course content to bridge gaps in your students‘ understanding

“So, what is academic integrity?” I might ask my students when beginning a lecture on this subject. “Who has come across this term before?” Every year, the silence in the lecture hall (or indeed the online meeting room) signals to me that nobody has heard this term before, and the thought of having to explain a way of thinking from scratch is extremely daunting.

I teach a cohort of 340 postgraduate students, almost all of whom are international students from China. I started specialising in academic integrity a couple of years ago, and I’ve found that introducing the subject to my students does little to decrease the number of student assignments being referred to the academic integrity department for investigation.

As an academic integrity officer, I also investigate cases and meet with students who have been reported as having breached academic integrity, whether in research conduct, coursework or assignments. I’ve noticed that many students lack an understanding of topics such as intellectual property, copyright and ethics, ideas that I had previously thought were close to universal. Mаny of the cases I have investigated weren’t slip-ups, where the student made a genuine mistake. These were more difficult conversations with students who seemed not to have the same baseline understanding of these ideas as I did. It felt as though their academic misconduct was intentional, although I didn’t believe this was the case.

- Advice for using English as a second language in higher education

- Read more: understanding and protecting academic integrity

- Targeted teaching: meeting students where they are

So, I set out to discover whether the gap was in my understanding of their perspective and, if so, where I could improve my practice. I put together a short write-up of my research to help organise my thoughts and make sense of my findings. Papers by other academics, particularly those writing about higher education abroad, confirmed my suspicion that there are other perspectives on this subject than the one I’m used to, having studied for my higher education qualifications in the UK.

How previous experience affects understanding of academic integrity

Academic integrity is closely linked with ethics and morality, according to Guy Curtis, of the University of Western Australia, which touch on wider cultural upbringing, and these are understood differently in China from how they are treated in many Western societies. A variety of conditions within the higher education system in China have caused what we would consider to be academic misconduct to flourish nationally, writes Tracey Bretag of the University of South Australia in her 2016 Handbook of Academic Integrity. Although, as the Chinese culture has an entirely different understanding of intellectual property and academic integrity, they would not consider it so.

Harmony is one of the qualities of Chinese society that strongly underpin the belief that all parts of a community may be used by its members for a greater benefit, and this includes individual intellectual property in the form of ideas. In a place where community is of much greater importance than the individual, it would be odd for an individual from this society to try to credit an idea to themselves. In applying this understanding to an academic classroom setting, it is clear where a cultural misunderstanding may arise, wrote lawyer and former Yale-China teaching fellow Peter Friedman in Forbes in 2010.

Let’s talk academic theory: learning incomes and social constructivism

Making a connection with the broader context from which students may have come is what Phil Race of the University of Plymouth refers to as learning incomes in his fifth-edition book, The Lecturer’s Toolkit. He suggests that the more we know about where students have already been, “the better we can help them to learn”. Practically, this means that engaging with your students to understand what they already know about a topic before giving the lecture is important preparatory work to do.

The social constructivism approach, where learning is largely based on students’ existing knowledge and previous experiences, wrote Richard Bale, of Imperial College London, and Mary Seabrook, of King’s College London, in 2021, is what helps educators engage in scaffolding. This then helps in pitching the learning at the right level for most students. In this way, you contextualise your teaching correctly for the students in front of you, rather than presenting a more general lecture that could be directed at anyone.

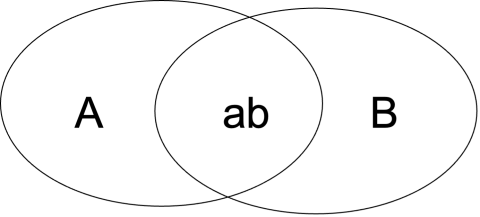

Peter Scales has also discussed Schramm’s model in relation to this. This model (see below) shows areas of knowledge of the lecturer (A) and the student (B) and where they intersect (ab). The model suggests that learning should be aimed at increasing the shared area (ab). From experience, the first step to move to the (ab) area should be made by the educator. It is our job to try to understand what the students already know and where there is a gap in knowledge or understanding and address it.

Schramm’s model of communication (1973)

Meet the students where they are

With consideration of the above observations, I made several improvements to delivering my session on academic integrity to my cohort of Chinese students.

In preparation for my improved lecture, I discovered that in Chinese, two words correspond to academic integrity. Xueshuchengxin is the positive framing to indicate desirable academic values of honesty and reliability. The negative framing symbolising academic misconduct in Chinese is Xueshubuduan.

Having introduced these words to align concepts via a more familiar route, I opened the lecture with anecdotes and scenarios that students could relate to, to make the topic easier for them to interpret. I then asked the students to reflect on their own experiences to involve their cultural backgrounds before introducing new concepts. This acknowledges that expectations around academic integrity in the UK may be different from what they have previously been exposed to.

With these and other improvements, such as the addition of peer-to-peer discussions (or breakout rooms, if hosting online) during the lecture, a clear explanation of the expectations of our university more widely and how this translates to assignments students may be working on, as well as a directory of links at the end to encourage further learning, I notice a better understanding of the topic across the cohort.

However, I don’t believe this to be the biggest takeaway. My biggest lesson learned was the importance of tailoring your content to your particular cohort and your students’ needs, whether these are cultural or of a different kind, such as language support or accessibility. I therefore find it useful to reflect more widely on the fact that what may be considered a well-prepared lecture on its own, out of context, may need significant modifications based on the cohort in front of you.

Julija Jones is a teaching fellow on the MA in global advertising and branding and a faculty academic integrity officer at the University of Southampton.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.