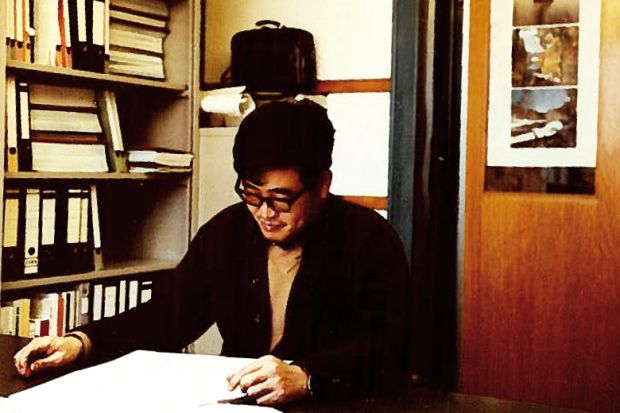

Weimin Wu’s career has spanned two eras in Chinese science: the Cold War period of hydrogen bombs and satellites, and the information technology revolution that spawned the internet.

“I’m the only person that bridged these two generations,” says the physicist, who, following a tumultuous life, has settled in the US and decided to set down his extraordinary story in his forthcoming autobiography, Life on the Cusp.

Wu was born in 1943 in Shanghai when the city was still under Japanese occupation. He was born prematurely after his mother fled from the Japanese military police pursuing her for taking part in a demonstration against the invaders.

Despite this tough start, Wu won an undergraduate place at the department of atomic energy at Shanghai’s prestigious Fudan University, where he was part of a secret night-time project that culminated in China’s first nuclear bomb in 1964.

Following this he travelled far to the west of China for graduate study at Lanzhou University, and it was here that he experienced the outbreak of China’s chaotic Cultural Revolution. Initially enthusiastic at the chance to sweep away “those bureaucrats and party functionaries who lorded over the common people”, as his autobiography puts it, Wu ultimately turned against the movement after his parents back in Shanghai were denounced and tortured, and his siblings sent away from the city.

But during this period of his life Wu became part of another chapter in the country’s scientific history, helping to crunch data that allowed China to launch its first satellite in 1970.

At the time, Marxist doctrine was unchallengeable in Chinese universities, Wu tells Times Higher Education. But ideological restrictions have faded and the ruling Communist Party “realises that you have to give scientists freedom of thinking”, he contends.

Last year, Tu Youyou became the first Chinese scientist to receive a Nobel prize for work carried out in China. She was honoured for an anti-malaria treatment developed from traditional Chinese medicine during the Cultural Revolution.

But other problems remain, Wu says. “Older people dominate [Chinese science], and the younger people have very little freedom,” the 73-year-old adds. Youthful scientists “don’t have anything to be afraid of”, he argues. “Sometimes you think they are crazy but often there is some truth” in their new ideas. Deference to age is far weaker in the US, he thinks.

‘Golden years’

In the relative calm of the late 1970s and the reform and opening period of the 1980s – when Wu says he experienced the “golden years” of his life – his scientific career took off in Beijing. He joined China’s Institute of High Energy Physics in 1979, and went abroad for the very first time to Switzerland. Despite being “copiously” sick at Zurich airport due to “the long flight, jet lag and over-excitement”, his book recalls, the trip began a period of international collaboration and would lead to what Wu describes as his greatest achievement: sending the first ever email from China.

Although another user, Qian Tianbai, is more widely credited as having sent the first message in 1987 – with the subject line “Crossing the Great Wall to Join the World” – Wu insists he sent one the previous year to a physics colleague in Geneva.

His pioneering message has been recognised by China’s internet administrator, the China Internet Network Information Center, which lists his email as the very first event in the country’s internet history.

In contrast to those early hopeful days, the internet in China is now synonymous with one thing: censorship. But efforts to wall off sites like Facebook and Google will not work, Wu thinks. “People will still find a way around it,” he tells THE.

In 1989, Wu filmed the unfolding protests in Tiananmen Square and managed to convince a visiting Italian physicist to smuggle the film to Europe. He saw protesters lying down in front of army tanks to stop their advance; but once the shooting began, he ran home. “I was definitely not a hero, and most definitely a death-fearing coward,” his autobiography recounts. Fearing persecution for his involvement, he later fled to the US.

Wu is not nearly as critical of the current party as one might expect from a veteran of Tiananmen Square. He does find it “ridiculous” that email accounts from certain providers are blocked in the country – notably Gmail – but tells THE the current leadership is “very capable” and much more “open-minded” than some predecessors. The main target of his anger is the party hardliners who ordered the army to crush the 1989 demonstrations.

Although China’s economy is slowing and the conditions for graduates are tough, Wu thinks that the chances of a similar student uprising on China’s campuses today are remote. The atmosphere on campuses is now “totally, totally” different and the students he talks to are “quite happy with their studies”.

Now happily living in the US but often visiting China to promote scientific collaboration, Wu remarks at the end of his autobiography: “My life is like the random Brownian motion of a particle, to be tossed around in one storm after another.”

Life on the Cusp, by Weimin Wu, will be published in May by World Scientific Publishing.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Turbulent past, promising future: Weimin Wu on China

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login