I have always enjoyed reading the books section in Times Higher Education but especially so just before the end of the academic year, when the summer reads feature is published.

I like to see what other academics claim to be reading over the summer to make them sound more interesting. I have contributed to this section previously, although it would be pretty pointless my contributing again because I have read the same book every summer since 2001: George Orwell’s The Road to Wigan Pier.

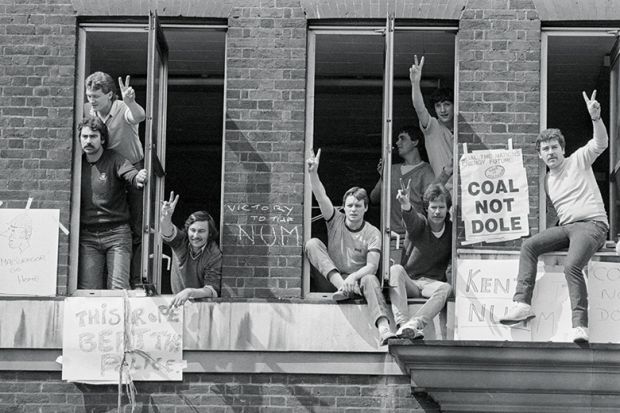

This was the book that I was given to read during the miners’ strike in 1984 by a supporter of my striking family who was an editor at Penguin books. I was 16 and I remember reading the passage that explained how the middle classes believed the working class smell. This upset me. It hurt me. My grandparents, who raised me and who I loved dearly, would have been starting out their lives together in 1937 and the passage hurt me so much that I didn’t read the book again until I went to university in 2001. I have read it every year since.

I have to admit that I find Orwell fascinating. He writes in such a contemptuous manner that I cannot help but admire his honesty in disliking most people who he meets, although the annual pull to this particular book is not entirely obvious. I enjoy how Orwell – writer, journalist and class traitor – marches his way around the North, drinking tea in miners' homes, commenting on how dirty, undernourished and short the working class are.

I come from one of those mining towns and my grandparents would have been the same as those families he met. By the time I was born in the late 1960s, not that much had changed if I’m being honest. And my recent research in the mining towns in Nottinghamshire tells me that some things have still not changed.

This year, The Road to Wigan Pier celebrates its 80th birthday. The reason that I read it every year is because I always wonder what George would say about the current goings-on in the British political system. He never lets me down. Reading Orwell year after year and applying him to contemporary situations is something that I really enjoy, but also value.

In part one, Orwell goes to the northern industrial towns of Sheffield, Rotherham and Wigan, noting down what he sees: how utterly damaging the poor housing, unemployment and class snobbery is to working-class families – physically, spiritually and emotionally. He also notes that if the middle class had to live in such hard times, they would totally go to pieces.

However, reading the book this year, the real insight for me comes in part two: Orwell’s account of the left-wing politics that were rising among the middle class in the interwar period. This is an absolute delight for me as a working-class academic. Orwell, the old Etonian, sees through his own class. He recognises who they are and he shreds them to pieces like only a class traitor can.

I am reading The Road to Wigan Pier in 2017 – in the midst of elections in Europe, post-Trump and entering Brexit. Orwell’s words on “snobbery” and the way the middle class organise themselves in times of insecurity and change, should be on everyone’s reading list.

Orwell is writing in the 1930s. The working class are suffering in a great recession, where thousands of men are unemployed full time, thousands more are in low, precarious work and thousands of poor working-class families are on the street. Everyone is suffering from the consequences of the Great War and there is a universal anger at the superior classes who led millions to their deaths.

He notes that there is a rising “middle class” who are not reactionary but in fact “advanced”. They are scholars and academics and they are embracing socialism. Orwell muses that this group might start voting and campaigning for Labour; however, little else changes with these “advanced radicals”. They still habitually socialise only within their own class, their “tastes” do not change; they are still more comfortable with their own class, even if members of their own class do not agree with their politics.

Orwell notes that the “advanced Left” still hold on to their bourgeoisie tastes: their wine, the food they eat, the company they keep. The places they frequent are still strongly bourgeois even though the conversation over the wine might be of a “left radical” nature. He also notes that their comradely thoughts of socialism never really go further than what they may do “in theory”.

In the 1930s, these advanced radicals “idealised the proletariat” and imagined them as the strong, brave, front line to capitalism – the meat, the brawn, the foot soldiers. They saw themselves as the thinkers; the organisers of equality. In 2017, this is far from the truth. The new advanced radicals – the bourgeois middle class who inhabit our universities, thinktanks, the media, and the top positions in our charities – dislike the proletariat intensely. The proles in 2017 are seen as stupid, ignorant and racist, not able to think further than the national anthem.

They are not on the front line of any fight to end capitalism. They are, in fact, worse than fascists; they have anger and hatred, but with no ideology. And this, to the new advanced radicals of 2017, is unforgivable. We must have ideology. Ideology is the thing that separates our politics into good and bad; honourable and dishonourable; educated and uneducated. Yet in the same way that Orwell’s intellectuals saw themselves outside the “class racket”, members of the new advanced Left in 2017 also see social class as an unfortunate disadvantage – but often a disadvantage that they do not see as entirely legitimate.

They understand that they must, as Orwell says, “jeer at the House of Lords, the military top brass, the Royal Family, hunting and shooting, and boarding schools”. This jeering, Orwell says, is an “automatic gesture” where class advantage at the top for the new advanced Left is abhorrent. Yet their outrage does not filter to the bottom of society, and it definitely does not allow them any room for reflexivity about their own spaces.

Neoliberal language such as “team fit” and “potential” allows their class snobbery and prejudice to thrive and reproduce while not being in the “class racket” themselves because they know too well that abolishing class inequalities means abolishing their own privilege. That, they believe, is why ideology is key. They must not do anything practical until they have secured the right ideology among themselves, in their offices and their lecture halls.

Lisa Mckenzie is research fellow in the department of sociology at the London School of Economics.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?