It is a complicated thing to review a book that is published hard on the heels of an author’s death. Linda Nochlin, the renowned feminist art historian, passed away at the end of October 2017 at the age of 86. Her book Misère has just come out. I am relieved that no critical hesitation is necessary posthumously. The book is a fitting memorial to her life and career.

The subtitle perhaps misstates the heart of the book. Rather than a synoptic or encompassing work, it focuses on various moments in the documentary impulse of 19th-century artists, illustrators, journalists and photographers. While some painted the poor in traditional or sentimental ways, Nochlin is most drawn to those who change the game, showing us through colour, line, composition and texture the grittiness of poverty.

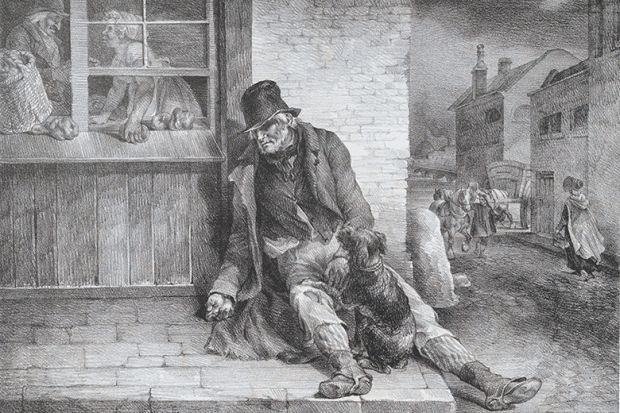

The two pictures that stand out for her are Pity the Sorrows of a Poor Old Man! by Théodore Géricault and The Charity of a Beggar at Ornans by Gustave Courbet. In the former, an old man, clearly having lived a better life, is now reduced to lying against a building in London. The awkward angle of his leg thrust into the street, his hand unconsciously open for alms, along with a faithful dog staring up at his face, create, according to Nochlin, “a diminished yet intense and intensely moving synecdoche of lost feeling and humanity, caught within the immense social uncaringness” of 1820s London.

The second painting shows an emaciated old man, twisted and gangly, putting a coin into the hand of a young Romany child as his mother watches. The boy covers his nose as he takes the coin, indicating how bad the man smells. According to Nochlin, who wrote one of the major books on Courbet, this painting “constitute[s] a link in the chain of Courbet’s images engaging…with the dominating issue of misery and the indigent and marginalized human beings that bodied it forth”. It is unusual to put Courbet’s erotic paintings on a continuum with those devoted to the plight of the poor, but Nochlin makes a convincing case.

The book also addresses the larger issue of how one represents misère. Poor people often cannot and by and large do not create representations of themselves. That task has been left to the middle classes, who of course represent the poor in ways that correspond to the expectations of viewers rather than reality. While Nochlin does not enter into the more philosophical aspects of this question about truth, reality and representation (except to refer us to Stuart Hall’s book on the subject), the question remains.

The 19th century was devoted, as Michel Foucault reminds us, to the endless study of the deviant – whether criminals, the insane, women or the poor – and because of that, a huge repository of data and documentation exists about the living conditions of the poor, their social and sexual lives, their culture or lack of it, and so on. On the one hand we have this database, and on the other representations by individual artists who might have had passing contact with the poor but would not have experienced their world in depth. But these are the most available accounts we have, and therefore their art becomes by fiat reality. Nochlin’s analysis generally blurs this problematic bifurcation between art and life.

Although she touches on this subject, she does not really have the space or the inclination to place the artistic impulse in the context of this massive descriptive project in progress in the 19th century. Indeed, if there is a through line to the book, it would be that poverty was depicted as picturesque and idealised in 18th-century drawing, that the 19th century made the move to realism and a documentary style, while our own time has dropped that approach. The 19th-century artists Nochlin likes found a style that signalled the nature of this new “truth”. As she notes: “The less aesthetically pleasing and consciously organized such an image might be, the more authentic, the more true to actual experience itself it might be considered.” Yet “the most advanced artists of the later twentieth and early twenty-first centuries have been engaged with the idea of unrepresentability – the idea that since Auschwitz one cannot directly represent the horrors perpetrated upon humanity, or must…present them indirectly”.

Aside from this “then and now” perspective, Nochlin does not provide us with a more graduated and nuanced set of tools to see the various styles and approaches to the poor in the 19th century. Yet she cannot be faulted for this limitation because the book itself is a slim work. What she does very well, of course, is to remind us about issues of gender. There is notably a chapter on prostitution, which highlights that women suffer from poverty more than men and that prostitution was a viable and probably transitory way for poor women to monetise themselves. But, as with the poor, the vision we get of prostitutes is from middle-class males.

The author therefore begins with the “fantasy-fueled representations of the sexual female” that have been the stock-in-trade of depictions of prostitutes. Highlighting two paintings that represent women as temptress – Paul Cézanne’s The Eternal Feminine and Gustave-Adolphe Mossa’s She (Elle) – she moves on to the work of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Edgar Degas. This gives us a more intimate, documentary and insider view of the life of the prostitute that includes female sociability; humiliation at the required medical examinations; and the paradoxical irrelevance of men, who are only ever seen at the margin of Degas’ monotypes, barely visible. For Nochlin, the representation of misère loses its mysterious prurience in such works and focuses on the banality and boredom of the life of these poor women.

A quirk of the book is its unaccountable switching back and forth between the 19th century and now. For example, in the chapter on prostitution in the Second Empire, Nochlin spends a few pages on the 2015 exhibition Splendour and Misery: Pictures of Prostitution, 1850-1910, at the Musée d’Orsay. She repeats this move in a chapter on the Irish Potato Famine, in which the second half is devoted to late 20th- and 21st-century memorials. She does this yet again when talking about the depiction of poverty in the 19th century and then by contemporary artists. In such a slim book with a large theme, does it makes sense to keep shuttling between the historical main subject and 21st-century art and representations? It doesn’t make much editorial sense, although one understands the impulse to contextualise the then with the now.

One very disappointing aspect of the book is that, while it is amply illustrated, it is printed in an almost chapbook format. What this means is that many wonderful illustrations are too small to see clearly and the detail therefore gets lost. What a slight to the memory of someone who was famous for her attention to detail! It is regrettable that Thames and Hudson could not have found the largesse to provide Nochlin with a truly fitting memorial at the end of a distinguished career.

Lennard J. Davis, distinguished professor at the University of Illinois at Chicago, is working on a book about the representation of poverty.

Misère: The Visual Representation of Misery in the 19th Century

By Linda Nochlin

Thames and Hudson

176pp, £24.95

ISBN 9780500239698

Published 12 April 2018

Linda Nochlin, who died last October at the age of 86, was professor emerita of modern art at New York University Institute of Fine Art. She studied philosophy at Vassar College, followed by an MA in English at Columbia University and then a PhD in the history of art at NYU. She taught at Yale University, the City University of New York and Vassar before returning to NYU until she retired in 2013.

A leading feminist art historian, Nochlin was probably best known for her 1971 essay “Why have there been no great women artists?”, although she also published widely on the work of Gustave Courbet, other 19th-century Realists and “Orientalist” motifs in Western art.

“It was the negotiation of painting and power, beauty and social justice that exercised [Nochlin] throughout her life,” wrote Tamar Garb, professor in the history of art department at UCL, in a tribute published in The Art Bulletin after her death. Such commitments “provid[ed] the basis for her irreverence toward art history’s hierarchies: its adulation of great men, its assumptions around ‘genius,’ its devaluation of ‘craft,’ and its gendering of genres alongside its circumscription of eroticism to masculinist pleasures and tastes”.

Nochlin also played a crucial role in promoting art by women. She co-curated exhibitions on Women Artists: 1550-1950 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (1976) and on Global Feminisms at the Brooklyn Museum (2007). The 30th anniversary of her “no great women artists” essay was marked by a conference at Princeton University and then a book edited by Carol Armstrong and Catherine de Zegher titled Women Artists at the Millennium (2006). Here, Nochlin revisited her original argument and the key changes she had seen over three decades, while noting: “We will need all our wit and courage to make sure that women’s voices are heard, their work seen and written about.”

Matthew Reisz

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Wretched, down and drawn

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login