Simon Reid-Henry, reader in geography, Queen Mary University of London

Small books that gracefully submerge you up to your neck in some eternal matter rank among the most treasured of my possessions. Richard Tuck’s The Sleeping Sovereign: The Invention of Modern Democracy (Cambridge University Press) is one of these. Tuck’s careful parsing of “we” from “the people” (and his treatment of political agency) has proven particularly salient in this year of knife-edge referendums and Trumpism. In more leisurely hours (although with even more knives at play), I am nearing the bloody conclusion of the life of Marcus Tullius Cicero, as told in Dictator (Arrow), the last volume in Robert Harris’ brilliant fictionalised trilogy. I hope to get there before Christmas, else bloodied togas may begin to merge with Santa suits. And that would not be very seasonal.

Louise O. Fresco, president, Wageningen University & Research, the Netherlands

Weaving in stories about relatives and patients, Siddhartha Mukherjee’s The Gene: An Intimate History (Bodley Head) portrays the application of genetics as a potentially dangerous as well as a truly liberating idea. How much risk are we willing to take? The Gene shows that however important our genes are, we cannot be reduced to our genes alone.

Just like the protagonist of Yentl, Barbra Streisand had to overcome enormous resistance. But she would not be stopped – by her looks, her Jewish identity, a lack of resources or even her insecurity. She became a symbol of empowerment. Neil Gabler’s Barbra Streisand: Redefining Beauty, Femininity, and Power (Yale University Press), part of Yale’s Jewish Lives series, should inspire all students to persevere.

Sir Howard Davies, professor of practice, Sciences Po, Paris

All That Man Is (Jonathan Cape) by David Szalay was on this year’s Man Booker Prize shortlist. I’m not astonished that it didn’t win: it is made up of nine almost unrelated sketches. Szalay paints a bleak yet fascinating picture of European man today. I was entertained and depressed in equal measure. The Man Who Knew: The Life and Times of Alan Greenspan (Bloomsbury) is Sebastian Mallaby’s new biography of the former chairman of the US Federal Reserve. It addresses what is still the big question about the financial crisis: could and should the central banks have seen trouble coming and taken steps to head it off? The answer he gives, which I like, is “yes”. So a happy case of confirmation bias from a very readable account.

Cheryl de la Rey, vice-chancellor, University of Pretoria

Both my choices are autobiographies, as I have a professional interest in psychobiographies. In a quiet, gentle tone, N. Chabani Manganyi’s Apartheid and the Making of a Black Psychologist: A Memoir (Wits University Press) divulges how one of South Africa’s leading intellectuals navigated the harsh contours of racial exclusion to pursue a remarkable career as a psychologist. As the story of Manganyi’s life unfolds, the reader gains insight into how the academic discipline and professional practice of psychology in South Africa was shaped by apartheid. Helen Zille’s Not without a Fight: The Autobiography (Penguin Random House) is the story of the feisty and often pilloried journalist and politician who carved inroads into South Africa’s townships to win votes for the official opposition party. Zille reveals the behind-the-scenes political machinations involving major political figures and, in doing so, gives insight into the politics of contemporary South Africa.

Shelly Asquith, vice-president (welfare), National Union of Students

Lorenza Antonucci’s Student Lives in Crisis: Deepening Inequality in Times of Austerity (Policy) is a fantastic, if bleak, look at students’ experiences of education in the context of neoliberal higher education reforms and austerity. In particular, it sheds much-needed light on the impact that growing inequality and marketisation in the sector are having on students’ mental health. Jon Bird’s Leon Golub Powerplay: The Political Portraits (Reaktion) accompanied a Golub exhibition at the UK’s National Portrait Gallery this year. This book, documenting the work of the anti-war artist/activist, is a work of art in itself, beautifully weaving together portraits with observations about their political significance, both historically and to the painter.

Siva Vaidhyanathan, Robertson professor in the department of media studies, University of Virginia

The simple story of the 2011 Arab uprisings rested on social media. Marwan M. Kraidy tells the real story in The Naked Blogger of Cairo: Creative Insurgency in the Arab World (Harvard University Press). The crucial instruments of protest were corporeal, not digital. Echoes and representations of bodies through various media (satellite television as much as social media) moved hearts and minds. Bruce Springsteen’s autobiography Born to Run (Simon & Schuster) took me back through my life via his saga and his songs. He remains the romantic bard of deindustrialised America. You can’t understand my country without Bruce Springsteen.

Anna Watts, associate professor of astrophysics, University of Amsterdam

This year it’s hard not to empathise with Cixin Liu’s astronomer Ye Wenjie, who, despairing of humanity, transmits Earth’s location to hostile aliens. Death’s End (Tor), which concludes Liu’s Three-Body Trilogy, merges brilliant technical imagination with a searing analysis of how scientists, politicians and officers react. I was once called a dreadful role model for making scientific motherhood “look hard”. If you crave picture-perfect heroines, then biogeochemist Hope Jahren’s memoir Lab Girl: A Story of Trees, Science and Love (Fleet) is not for you. Her brutally honest ride through the frustration, guilt, bafflement and joy of her life in science made me laugh, curse and cry.

Glyn Davis, vice-chancellor and professor of political science, University of Melbourne

The University of California is an anomaly – brilliant public policy in a nation marked by private endeavours, and a university “system” that has endured for two generations but is now under attack. Following its subject, Simon Marginson’s The Dream Is Over: The Crisis of Clark Kerr’s California Idea of Higher Education (University of California Press) inspires and distresses all at once. In Switzerland (Currency Press), playwright Joanna Murray-Smith delivers an eloquent double-hander. An old author and young publisher argue about the artifice of writing amid tall peaks of fame and place. First performed in Sydney, this new work from Australia’s leading playwright confirms her global standing.

Sara Goldrick-Rab, professor of higher education policy and sociology, Temple University, Philadelphia

The crisis facing African American men in the US is a dysfunctional criminal justice system, but for African American women the problem is housing eviction, explains sociologist Matthew Desmond in his extraordinary ethnographic study Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City (Allen Lane). Evicting people from their homes is profitable for landlords, many of whom are themselves just trying to get by, but it creates devastating disruptions in the lives of the poor. One of the best routes out of poverty is through higher education, and in Make Your Home Among Strangers (Picador), Jennine Capó Crucet follows the trajectory of a young Latina from Miami as she pursues college at an elite school far from her family. The struggle to get ahead while not leaving behind those you love is real, and she captures it beautifully.

Sally Hunt, general secretary, University and College Union

Read for pleasure: Ali Smith’s Autumn (Hamish Hamilton). In a book billed as a post-Brexit novel, Ali Smith’s writing is a linguistically elegant reflection of time, past, present, dreams. Sometimes it feels random, but there are thoughtful jewels throughout: “Her ears had undergone a sea change. Or the world had…” Exactly so. I’m still puzzling as to which. Work-related reading: Employment Tribunals between claimants Mr Y Aslam, Mr J Farrar & Others, and respondents Uber B.V., Uber London Ltd and Uber Britannia Ltd. The tribunal ruling that Uber drivers are entitled to proper rights at work was my read of 2016. In this ruling, along with the exposé of Sports Direct, we are slowly lifting the lid on the “gig economy”. Colleges and universities should be on notice that we will be coming for them in the new year if they do not work with us to remove the scourge of insecure contracts at their institutions.

Kate Raworth, senior visiting research associate, Environmental Change Institute, University of Oxford

2016 has at least given us great books for our troubled times. The Good Immigrant (Unbound), edited by Nikesh Shukla, is a powerful collection of angry, funny and moving stories and essays about being black, Asian or minority ethnic in Britain today. It should become required reading for a new UK citizenship test – one to be taken by everyone who was born here, that is. We just as much need David Fleming’s Lean Logic: A Dictionary for the Future and How to Survive It (Chelsea Green). This wonderfully idiosyncratic A-to-Z is anything but lean: at 500-plus pages it is overflowing with Fleming’s lifelong philosophy of social and economic transformation. And it is wisdom waiting to be discovered.

William Kolbrener, professor of English, Bar-Ilan University, Israel

In Maimonides: Between Philosophy and Halakhah (Ktav/Urim), Joseph Soloveitchik’s lectures on The Guide of the Perplexed (reconstructed from 1951 student notes), the great modern rabbi – and theologian and philosopher – meets the greatest medieval Jewish philosopher. The Guide, Soloveitchik writes, “anticipates by 700 years much of 20th century theology”, making a case for Maimonides’ continued relevance, and not exclusively in Jewish studies. Moving to literary pleasures, Elena Ferrante, the pseudonymous author of the remarkable “Neapolitan novels”, has published her self-described “jumble of fragments” – essays, letters and interviews – in Frantumaglia: A Writer’s Journey (Europa Editions). When asked by one of many frustrated interviewers: “Will you tell us who you are?”, Ferrante responds, “I’ve published six books, isn’t that enough?” Emphatically “yes”, but Frantumaglia is still, and not just for Ferrante devotees, a great read.

Aihwa Ong, Robert H. Lowie distinguished chair in anthropology, University of California, Berkeley

In Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Duke University Press), Donna J. Haraway argues that to be truly present in our damaged Earth, we need to embrace a multi-species viewpoint. Like the lowly mosses – “We are all lichens now!” – we come to understand life and death by “making‑with” other organisms so as to ensure a liveable future for our species. Where Haraway leaves off, Ed Yong begins. I Contain Multitudes: The Microbes Within Us and a Grander View of Life (Bodley Head) explores our serendipitous entanglements with our most intimate co-species. Microbes make us flourish and die at will.

Kristin Andrews, associate professor of philosophy, York University, Toronto

We are lucky that 2016 saw the release of the two books I’ve chosen, as they both encourage us to develop skills that will help us to be better practitioners of this moral project we all share. Philosopher Owen Flanagan’s book The Geography of Morals: Varieties of Moral Possibility (Oxford University Press) examines psychology, anthropology and Eastern philosophy to argue for a more expansive understanding of morality. He shows that the Western emphasis on following principles is not the only way to be moral, that developing moral attention is essential, and he suggests ways that we can better morally educate our children. The Path: What Chinese Philosophers Can Teach Us about the Good Life (Simon & Schuster) is a short self-help book co-authored by Chinese history scholar Michael Puett and journalist Christine Gross-Loh. They suggest that common-sense beliefs about freedom, a true self, and rational choice about transformative life decisions all obstruct human flourishing, and instead we should see the aspects of goodness in our patterns of behaviour, and develop those through various kinds of moral exercise.

Carina Buckley, instructional design manager, Southampton Solent University

Thinking about the day job, I found Alke Gröppel-Wegener’s Writing Essays by Pictures: A Workbook (Innovative Libraries) a valuable addition to the study-skills artillery. It is non-threatening and colourful, and its creative presentation encourages students to embrace creativity, too. It presents new perspectives on writing through analogy and metaphor that makes academic work seem wholly achievable. The evolution of cognition remains an abiding interest for me, and Frans de Waal’s Are We Smart Enough to Know How Smart Animals Are? (Granta) did not disappoint. De Waal’s engaging and personal tone conveys his wonder at the natural world, as he argues that our understanding is limited only by the questions we ask.

Andrew Robinson, adjunct lecturer in physics, Carleton University, Ottawa

On a professional level, I’ve been perusing the latest crop of introductory physics textbooks for non-physicists. I was very impressed by the third edition of Physics for the Life Sciences (Nelson College Indigenous) by Martin Zinke-Allmang, Reza Nejat, Eduardo Galiano-Riveros, Johann Bayer and Michael Xiaoke Chen. It is a streamlined and elegant exposition of essential physics for life sciences. It’s also that rare flower, a Canadian textbook. For personal reading, the book I most enjoyed this year was one I reviewed for this magazine, Les Back’s Academic Diary: Or Why Higher Education Still Matters (Goldsmiths Press). Currently I’m in the middle of one of Richard Holmes’ earlier books, The Age of Wonder, and looking forward to reading Rebecca Rideal’s 1666: Plague, War and Hellfire (John Murray). For a scientist, I read a lot of history books.

Susan Rudy, senior research fellow in the School of English and Drama, Queen Mary University of London

Brexit. Trump. Syria. What a troubling year. But Donna J. Haraway’s Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Duke University Press) and Denise Riley’s Say Something Back (Picador) offer ways forward in despairing times. Feminist theorist Haraway argues against the illusion that humans are “self-made”. Rather, our current age – the “Chthulucene” – requires practices of “making-with”: “The task is to become capable, with each other in all our bumptious kinds, of response.” Poet Riley directs her plea – “say something back” – to her dead son, yet hers is nonetheless a political response to grief. Contemporary reality requires, as much as ever, “listening for lost people”. Both books are thus moving testimonies to the challenges we face and our desire to face them.

Rob Behrens, visiting professor at UCL Institute of Education and former independent adjudicator for higher education in England and Wales

The merit of Dave Rich’s optimistic, reasoned book The Left’s Jewish Problem: Jeremy Corbyn, Israel and Anti-Semitism (Biteback) lies not in its scholarship (there is no bibliography) but rather in its account of how parts of the Labour Left have used anti-racist credentials to eliminate even the possibility of their being anti-Semitic. All done with righteous indignation and no appreciation of how this is experienced by British Jews. Mark Singer’s Trump & Me (Penguin Random House) will disappoint those who believe that Donald Trump’s election as US president represents a personal epiphany on the road to statesmanship. Singer, a close observer, reports that Trump is a long-time “efficient schmoozer”, narcissistic, devoid of introspection and a man for whom ideal company is “a total piece of ass”. Alas, he says, “there is no ‘new’ Trump, just as there was never a ‘new’ Nixon”.

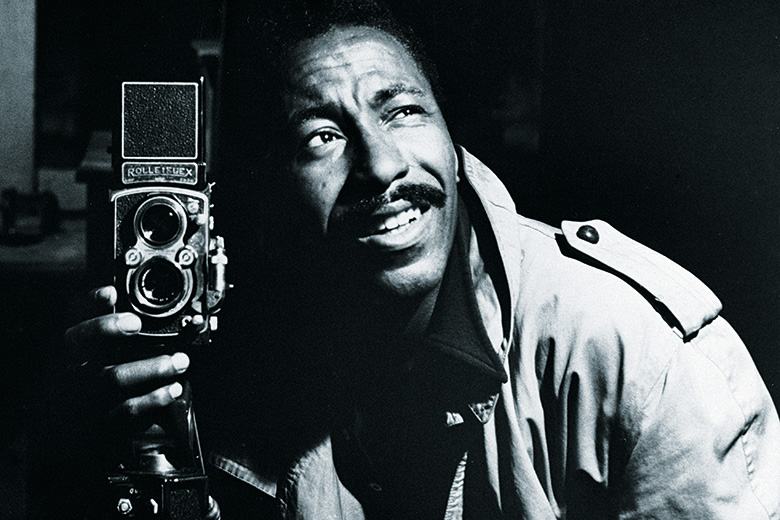

Victoria Bateman, fellow and director of studies in economics, Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge

After a dark political year, I’m finding solace this Christmas in Deirdre McCloskey’s Bourgeois Equality: How Ideas, Not Capital or Institutions, Enriched the World (University of Chicago Press). In what is the third volume of a magisterial series on the rise of the West, McCloskey highlights the importance of our freedom to strive. Alongside it, I’m looking forward to flicking through Gordon Parks: I Am You (Steidl), edited by Peter W. Kunhardt, Jr and Felix Hoffmann. A selection of works by the first African American photographer (pictured above) for Life and Vogue, it documents social change in the US between 1942 and 1978. Taken together, these books are a reminder of how far we’ve come and what we can’t afford to take for granted.

John Field, emeritus professor in the School of Education, University of Stirling

Is education really the great social equaliser? Education, Occupation and Social Origin: A Comparative Analysis of the Transmission of Socio-Economic Inequalities (Edward Elgar), edited by Fabrizio Bernardi and Gabriele Ballarino, offers a much-needed international look at the issues, subjecting Russia, the US and Japan along with 10 European countries to hard, systematic analytical scrutiny. Solid social science, essential for anyone interested in education and equality. I also enjoyed Grand Hotel Abyss: The Lives of the Frankfurt School (Verso), Stuart Jeffries’ collective biography of neo-Marxists who grasped the importance of culture to contemporary capitalism’s incorporation of the working class while remaining aloof from any actual political action. I read this to the sound of Ute Lemper singing Brecht and Weil.

Bernd Huber, president, LMU Munich

In The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The U. S. Standard of Living since the Civil War (Princeton University Press), the distinguished economist Robert J. Gordon provides a masterly analysis of the economic development of the US. His book offers not only a detailed historical account but also an insightful analysis of the nature and the underlying forces of economic growth. Its main conclusion is not optimistic: economic growth as we know it will largely vanish, and the contrast between this sobering insight and the optimism of Silicon Valley is one of the most fascinating aspects of Gordon’s study. In his novel Moskva (Penguin), Jack Grimwood takes the reader back to the wintry Soviet Union of 1985. It is a world without mobile phones, laptops or the internet, but with many signs of the declining power of the Soviet empire. In this landscape, a young British diplomat becomes involved in the search for the abducted daughter of the British ambassador. A gripping story with many fascinating and often sinister characters, and the perfect companion for a cold winter’s day.

Sunny Singh, senior lecturer in English and creative writing, London Metropolitan University

My two recommendations seem ever more necessary. The Good Immigrant (Unbound), edited by Nikesh Shukla, brings together 21 black, Asian and minority ethnic writers to push back against the anti-immigrant rhetoric that has swamped our public discourse since that near-forgotten euphoria of the 2012 London Olympics. By turns informative, poignant and powerful, this is a must for our perilous times. An Unreliable Guide to London (Influx), edited by Kit Caless and Gary Budden, extends the tradition of writing this city and turns it on its head. This collection of odd, complex and at times absurd stories set far from famous landmarks and glittering lights celebrates all that I love about London.

Jonathan Webber, reader in philosophy, Cardiff University

Two books stood out for me this year as timely reminders of our society’s fragile foundations. In At the Existentialist Café: Freedom, Being, and Apricot Cocktails (Chatto & Windus), Sarah Bakewell brilliantly illuminates how the ambitious philosophical analyses of a handful of writers have helped to shape the West’s cultural and political development since the war. Philippe Sands vividly portrays the struggles to establish genocide and crimes against humanity as offences in international law in East West Street (Weidenfeld & Nicolson). Both books indicate how deeply our civilisation depends on respect for reasoning and how much we will lose if raw power drowns out that respect.

Nagihan Halilog˘lu, assistant professor in civilisation studies, Fatih Sultan Mehmet University, Turkey

In Modern Art and the Life of a Culture: The Religious Impulses of Modernism (InterVarsity Press), Jonathan A. Anderson and William A. Dyrness explore art as a means to re-enchant the world, a theme I have been interested in for some time. It offers methods of approaching the intersection of religious and artistic experience, and provides a vocabulary and grammar of meaningful encounter. There’s re-enchantment of another order in Philip Eade’s Evelyn Waugh: A Life Revisited (Weidenfeld & Nicolson), as you would expect from any (re)telling of Waugh’s life. The book covers the familiar ground of his college antics, but also reveals the precarity of the writing profession even when you’re famous, living from one commission to the next and exploiting friends’ hospitality for a peaceful place to write.

Sarah M. Springman, rector, ETH Zurich – Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zurich

Philipp Gut’s Champagner mit Churchill: Der Zürcher Farbenfabrikant Willy Sax und der malende Premierminister (Stämpfli Verlag) is highly recommended for those who are fascinated by personal motivations and last-century world politics, and who can read German! Anglo-Swiss relationships between a Swiss art critic and painter, Charles Montag, and his famous pupil, Sir Winston Churchill, evolved over several decades and expanded to include the Swiss paint manufacturer and entrepreneur Willy Sax. Subsequently, Sax became the statesman’s confidant on painting, while also acting as an interface between Churchill and Swiss politics. The book is illustrated with delightful anecdotes and photographs, with a fascinating backdrop of key events in world history and the underpinning theme of a common passion for painting.

Elaine Showalter, professor emeritus of English, Princeton University

Clear, concise and surprisingly reassuring, John B. Judis’ The Populist Explosion: How the Great Recession Transformed American and European Politics (Columbia Global Reports) explains the difference between left-wing and right-wing populism, including Donald Trump, and offers some hope that the American upheavals of 2016 will not become an earthquake. Cathleen Schine’s novel They May Not Mean to, But They Do (Macmillan) – taking its title from line two of Philip Larkin’s This Be the Verse – explores the complications of caregiving in families, centring on a tough-minded octogenarian grandmother. Schine is unsparing, graphic about ageing and death, but also very funny.

Meric Gertler, president, University of Toronto

For work: Robert Kanigel’s Eyes on the Street: The Life of Jane Jacobs (Alfred A. Knopf). Jane Jacobs (pictured above) remains one of the most influential – and controversial – figures ever to have written about cities. She would have been 100 this year, so Kanigel’s biography is both timely and welcome, documenting how Jacobs altered the shape of New York, her adopted Toronto, and indeed our thinking about cities. For pleasure: Elmore Leonard’s Charlie Martz and Other Stories: The Unpublished Stories (Weidenfeld & Nicolson). When it came to crime novels, Leonard was the master of style and economy. And nobody wrote dialogue better than he did. This volume brings together 15 stories from his earliest days as a writer. Although he was still developing his craft, his inimitable style already comes through clearly.

Akwugo Emejulu, senior lecturer, Moray House School of Education, University of Edinburgh

Gloria Wekker’s White Innocence: Paradoxes of Colonialism and Race (Duke University Press) dismantles cherished Dutch self-representations – that they are a fair and tolerant country – to demonstrate how a racialised social order is enforced but collectively denied. Analysing subjects ranging from Zwarte Piet to Pim Fortuyn, Wekker challenges Dutch claims to “innocence” that work insidiously to undermine racial justice. If you’re interested in understanding the murky racial politics underpinning Donald Trump’s election, I’d urge you to read Colson Whitehead’s The Underground Railroad (Fleet). Following the journey of Cora, a runaway slave, we encounter differing conditions of slavery but always the universal project to exploit, dehumanise and exterminate.

Shane O’Mara, professor of experimental brain research, Institute of Neuroscience, Trinity College Dublin

I’d like to nominate two non-fiction books, both of which have changed the way I think. Tom Gash’s Criminal: The Truth about Why People Do Bad Things (Allen Lane) should be read by everybody. What we think are the causes of crime, and the actual causes, tend to be different things, leading to terrible policy prescriptions to “cure” crime. Many crimes arise because of simple opportunity, and environmental redesign (and some measure of self-control training) would result in major falls in crime. In The Stupidity Paradox: The Power and Pitfalls of Functional Stupidity at Work (Profile), Mats Alvesson and André Spicer have written an entertaining and sadly all-too-true book about organisations. Something wonderful and disheartening on every page.

Angelia R. Wilson, professor of politics, University of Manchester

Emerging from your echo chamber, wondering what the *^%& just happened in the US elections? In Tea Party Women: Mama Grizzlies, Grassroots Leaders and the Changing Face of the American Right (NYU Press), Melissa Deckman’s research offers a much-needed corrective to the assumption that Trump supporters are uneducated white men. Claiming to be “authentic feminists”, Republican women are gun-toting protectors of family, faith and freedom. In Grace (Counterpoint), Natashia Deón’s voice, like that of Toni Morrison and Alice Walker, offers a haunting narrative of the histories of African American women. This heartrending tale of love between a mother and daughter defines grace as “getting a good thing, even when you don’t deserve it”. What an amazing and powerful first novel!

Curt Rice, president, Oslo and Akershus University College of Applied Sciences, Norway

One favourite is John C. Parkin’s F**k It: Do What You Love (Hay House), building on his 2014 mindfulness meditation, F**k It: The Ultimate Spiritual Way, and focusing on career development. As the head of my institution, I want to help my colleagues love their work; maybe a key is encouraging them to say just a little more often, “F**k it!” On the fiction front, I’m about halfway through Ian McEwan’s Nutshell (Jonathan Cape). He just never disappoints. I read First Love, Last Rites as a student umpteen years ago, and I’ve been a fan ever since. His plots draw me in, but I think it’s his way with the English language that brings me back. Such sentences!

Elizabeth Cannon, president and vice-chancellor, University of Calgary, and chair of Universities Canada

For work: Jim Dewald’s Achieving Longevity: How Great Firms Prosper through Entrepreneurial Thinking (Rotman/UTP) is a great book on how established organisations can adapt and succeed in a world of changing markets, technological advances and competitive environments, through entrepreneurial thinking. This is very applicable not only to companies but also to universities, which are adapting to a transformed world. For pleasure: Annette Verschuren’s Bet on Me: Leading and Succeeding in Business and in Life (HarperCollins). Verschuren, the former president of Home Depot Canada, tells the incredible story of how she approaches leadership from the perspective of authenticity and remaining true to oneself, while pushing the boundaries through transformational leadership.

Jennifer Rohn, principal research associate in nephrology, division of medicine, University College London

Scientific research is shrouded in mystery, misunderstood by popular culture and seldom revealed by its practitioners – especially women. Lab Girl: A Story of Trees, Science and Love (Fleet), an autobiography by Hope Jahren, strips bare her life as an academic palaeobiologist, exposing a ruthless and often sexist profession that still somehow manages to fulfil her dreams and ambitions. Wolves have been extinct for centuries in the UK. In Sarah Hall’s ravishing novel The Wolf Border (Faber & Faber), a rich earl employs zoologist Rachel Caine to reintroduce these magnificent but much-feared beasts into England. Caine, a lone wolf herself, must confront her own past to make peace with her future.

Steven Vaughan, senior lecturer in law, University of Birmingham

Think of any corporate scandal in recent years (VW, Toshiba, Valeant) and the question inevitably recurs: “Where were the lawyers?” In answering that question, in The Inside Counsel Revolution: Resolving the Partner-Guardian Tension (Ankerwycke), Ben W. Heineman (who spent almost 20 years as general counsel at GE) suggests that in-house lawyers need to tread a path between subservience to their employer and professional independence, acting as the guardians of the corporation. Away from my desk, I am a not-so-secret fan of space opera science fiction. I want/need to be transported away from the day-to-day. And Peter F. Hamilton’s Night without Stars (Pan) has done exactly that: shape-shifting aliens and high tech. Pure bliss.

Susan Prentice, professor of sociology, University of Manitoba

Maggie Berg and Barbara K. Seeber’s The Slow Professor: Challenging the Culture of Speed in the Academy (University of Toronto Press) is a much-discussed manifesto that has launched a vitally needed conversation on the importance – and pleasures – of protecting open enquiry from the frantic pace of the modern academic assembly line. Karen Dubinsky’s Cuba Beyond the Beach: Stories of Life in Havana (Between the Lines) is a testament to such rich scholarship. The fruit of more than a decade of extended sojourns in Cuba, Dubinsky’s book offers piercingly clear-eyed insights into the country. By turns affectionate and exasperated, this timely exploration of the resilience of Habaneras/os arrives just as the US lifts its embargo and the formerly closed country opens up.

G. J. (Bert) van der Zwaan, rector magnificus, Utrecht University

Helga Nowotny’s The Cunning of Uncertainty (Polity) may not have been the best book I read in 2016, but it is certainly the most intriguing one. As a former president of the European Research Council, Nowotny has been part of a system that funds more and more low-risk research, and that uses h-index and rankings to predict the outcome. Here, she makes a convincing plea for serendipity, for free academic enquiry. A plea for change!

In the beautifully written and composed novel The Noise of Time (Jonathan Cape), Julian Barnes presents an impressive narrative of personal integrity. At first glance, he is unsparingly describing the shameful acts of a great artist living in a totalitarian system. But the book is really about the everyday battle between good and bad, and the courage to soldier on in spite of bad choices.

Sir Robert Worcester, visiting professor of public opinion and political analysis, King’s College London

Both my choices are for work and pleasure. Both are seriously well-written books for serious people, and each is a pleasure to read. Lord (Igor) Judge’s The Safest Shield (Hart) is a compilation of lectures, speeches and essays on a wide variety of subjects. Readers of Times Higher Education are their natural targets. The collection’s title refers to the rule of law; its content ranges widely, from advocacy to constitutional change, sovereignty, human rights, and almost all should be of relevance to this magazine’s readers. What can be more relevant today? The same can be said for Enough Said: What’s Gone Wrong with the Language of Politics? (Bodley Head) by Mark Thompson, the former BBC director general and now president and CEO of The New York Times Company. Think back to what was said and who said what in the US presidential election, and then look to Thompson’s book for cogent answers.

Lorenza Antonucci, senior lecturer in social policy, Teesside University

In How Will Capitalism End? Essays on a Failing System (Verso), Wolfgang Streeck abandons the idea of reforming capitalism put forth in his earlier work to forecast the end of capitalism. While I remain unconvinced by his prophecy, the paradoxes and questions raised by this collection of essays will be at the centre of social research for years to come. In ‘Vladimir Mayakovsky’ and Other Poems (Carcanet Press), the poet James Womack has put together the comprehensive selection of Mayakovsky’s poems I have long been waiting for. His fresh translation allows English readers to appreciate the non-aligned and passionate personality of the Russian poet. I recommend a few lines twice a day to protect against dry academic writing.

Mark Berry, senior lecturer in the department of music, Royal Holloway, University of London

Unlike some, I have rarely taken an overtly hostile attitude towards the musical works I study; criticism generally benefits from a degree of sympathy. William Cheng’s Just Vibrations: The Purpose of Sounding Good (University of Michigan Press) goes further. Embracing queer struggle, Cheng questions shrill negativity and suggests greater value in a more empathetic, reparative and indeed therapeutic approach to music and musicology. Is it impossible? Maybe, yet “there is no alternative”. The post-Adornian dialectics questioned above return with a vengeance in British Left politics. Richard Seymour’s Corbyn: The Strange Rebirth of Radical Politics (Verso) not only shows how, amid Labour Party decline, Jeremy Corbyn and his supporters challenged the neoliberal consensus, but also considers the possibility of success and what form that might take.

Judith Clifton, professor of economics, University of Cantabria, Spain

Herbert Obinger, Carina Schmitt and Stefan Traub’s The Political Economy of Privatization in Rich Democracies (Oxford University Press) is a valiant attempt to compile a new quantitative database to assess the extent to which countries in the West have privatised their public sectors. It goes beyond summing up privatisation proceeds to chart the evolution of the size of each country’s public sector over time, thus really showing the effects of privatisation dynamically. Too often in academia, scholars work in silos and don’t read across other subdisciplines – but this can often be where the most interesting work is produced. Raj Chari’s Life after Privatization (Oxford University Press) sheds an illuminating cross-disciplinary light on privatisation by looking at how one of its consequences was the creation of new multinational corporations.

Felipe Fernández-Armesto, William P. Reynolds professor of history, University of Notre Dame

All books are work to me: I’m interested in everything and despise lines of demarcation. Of new academic books in the humanities I applaud Mark Thompson’s innovative, vivid, moving Birth Certificate: The Story of Danilo Kiš (Cornell University Press). Sensitively assembled fragments reconstruct the life and thought of Kiš, the exemplary Montenegrin dissenter from communism and nationalism. A politically incorrect thriller is, for me, the year’s best novel: in Falcó (Alfaguara), Arturo Pérez-Reverte – dynamic and coruscating – tells a Spanish Civil War spy story. The Falangist hero, who defies bien pensant orthodoxy, with virtues as well as vices, faces an impossible mission: to redeem his leader from Republican death row across ideologically ambiguous frontiers.

Kylie Jarrett, senior lecturer in media studies, Maynooth University

An edited collection that is coherent and consistent is a rare beast. The Post-Fordist Sexual Contract: Working and Living in Contingency (Palgrave Macmillan) is such a thing. Edited by Lisa Adkins and Maryanne Dever, its underlying feminist premise is that the personal and the economic are mutually informing, leading to complex analyses. More politically useful is The Moral Case for Abortion (Palgrave Macmillan) in which Ann Furedi, the head of the UK pregnancy advisory service BPAS, argues her way through the minefield of arguments for and against abortion. She cogently defines the kind of ethical pro-choice position needed wherever reproductive rights are under threat.

Mike Marinetto, lecturer in business ethics, Cardiff University

It’s unusual these days to recommend academic books – their gouged-up prices, and Klee-like covers, tend to make them personae non gratae. I will make an exception for Maggie Berg and Barbara Seeber’s The Slow Professor: Challenging the Culture of Speed in the Academy (University of Toronto Press). I came across the book as I was working on a polemical essay ranting about “fast food research”. The Slow Professor has a manifesto-like quality. But there are more scholarly insights packed into its slim 90-odd pages than you get in longer academic tomes. A must-read, but do take your time. The most addictive read of 2016 for me was Junot Díaz’s The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao – but it was published in 2007. As for real reading pleasure, the honours go to Sarah Bakewell’s At the Existentialist Café: Freedom, Being, and Apricot Cocktails (Chatto & Windus) – a great example of literary non-fiction.

Graham Farmelo, by-fellow at Churchill College, Cambridge

Too many books are written about Winston Churchill, but some aspects of his life still remain to be explored. The historian Kevin Ruane demonstrates this in his excellent Churchill and the Bomb in War and Cold War (Bloomsbury), which is thorough in its analysis and scrupulously fair in its judgements. In the world of fiction, we are not living in a golden age, but Sebastian Barry’s Days without End (Faber & Faber) is a masterpiece for the ages. He makes every word count in this wonderfully resonant story set in 19th-century America. Every one of its 259 pages is a joy, several of them indelible.

Clare Bambra, professor of public health geography, Durham University

Michelle Addison’s Social Games and Identity in the Higher Education Workplace: Playing with Gender, Class and Emotion (Palgrave Macmillan) is a well-written book by an early career researcher that explores game-playing in British universities and the effects of class and gender stratifications on our workplace identities. With a sophisticated theoretical framework, this book is essential reading for all of us who are struggling to survive and thrive in the neoliberal academy. Tony Parsons’ The Slaughter Man (Century) is the latest in the DC Max Wolfe series, a set of exciting and compellingly written thrillers with a charismatic hero. Set in a very atmospherically described East London, this adventure plays with themes around gentrification and ethnic tension while still providing a welcome release from the daily grind.

Sir David Bell, vice-chancellor, University of Reading

As head of the Policy Unit for Harold Wilson and Jim Callaghan, Bernard Donoughue was the consummate 1970s political insider. Twenty years later, he made a comeback that is captured brilliantly in his book Westminster Diary: A Reluctant Minister under Tony Blair (I. B. Tauris). Via his acerbic and witty pen, the early New Labour era is dissected sympathetically but not uncritically. Fictional politicians tend to be presented as either saints (The West Wing) or villains (House of Cards). Not so in Richard T. Kelly’s The Knives (Faber & Faber), in which a Northern Tory home secretary seeks to overcome an intransigent Civil Service and personal demons in tackling fundamentalism and immigration reform. The result is a nuanced and highly believable novel.

Mary Evans, centennial professor in the Gender Institute, London School of Economics

My non-work book is Pierre Lemaitre’s The Great Swindle (MacLehose Press). Lemaitre is better known for his beautifully written detective novels (excellent and strongly recommended), but here he turns to another form of crime: the criminal neglect of physically and mentally damaged French veterans of the 1914-18 war. It’s not a pretty tale, but it does convey an aspect of the war usually left unexplored: what it is like to be a survivor and how little support such people receive. The literal swindle is the corrupt selling of war memorials, but the book is as much about the swindle of military glory. My work book is Lynsey Hanley’s Respectable: The Experience of Class (Allen Lane). In a country in which cultural capital (aka signs of “class”) is so rigorously maintained and defended, it is extraordinary how few detailed discussions there are of its construction. Here is one: an autobiographical account of moving between, inside and away from class and classes and the experiences that accompany these shifts. At a time when “class” has come to have a revived place in our political landscape, this book provides a brilliant narrative of one life, and speaks to the hidden accounts of fantasies about class that inform our daily lives.

Hillegonda Rietveld, professor of sonic culture, London South Bank University

I’m enjoying Matthew Beaumont’s densely researched literary excavation in Nightwalking: A Nocturnal History of London (Verso). Undistracted by the daytime rush, the night offers a different city, its emptied streets revealing the lie of the underlying land, and the darkness blurring a sense of time and social boundaries. In The Oxford Handbook of Music and Virtuality (Oxford University Press), editors Sheila Whiteley and Shara Rambarran engage with a blurring of reality by bringing together an impressive collection on the virtual state of music, from holograms to crowdfunded music projects. Different in approach and purpose, both will be keepers.

Conor Gearty, professor of human rights law, London School of Economics

David Cole’s Engines of Liberty: The Power of Citizen Activists to Make Constitutional Law (Basic Civitas) tells us how the US Bill of Rights gets changed by political and legal pressure – how gun freedom becomes suddenly central, how gay marriage dramatically inserts itself, how Guantanamo gets tamed by legal but also political pressure. It’s a guide for those perplexed by how to respond to Donald Trump: get to work! Reading for pleasure? I’m too out of touch to be up to speed on today: this year I “discovered” the short stories of Alice Munro and Anne Tyler’s novel The Amateur Marriage (Vintage): fiction of timeless brilliance…

Vicky Duckworth, reader in education, Edge Hill University

For work, I choose Martyn Walker’s richly researched and well-written The Development of the Mechanics’ Institute Movement in Britain and Beyond: Supporting Further Education for the Adult Working Classes (Routledge), which has me picturing working-class women and men finding a space to free their mind from the often monotonous factory line. Enriching learning offers hope and at its best, like today, can be truly transformative. For leisure: Jeremy Seabrook’s Cut Out: Living without Welfare (Left Book Club). In a society where tabloid newspapers and “respectable” media alike crudely clump together and stigmatise those on benefits to justify cuts and yet more cuts to the welfare system, Seabrook offers a sharp counter-narrative soaked in humanity. Real stories of struggle and integrity challenge reductive stereotypes; identities are reclaimed.

Kate Nettell, digital media assistant for communications and marketing, University of Southampton

With beautiful artwork throughout, Emily Haynes’ The Art of Kubo and the Two Strings (Chronicle) offers a delicious delve into a wonderfully original and artistic animated film. Although it may be a little light on text, its focus on everything from concept to the final look of the film makes it an escapist book you can keep going back to. Mat Marquis’ JavaScript for Web Designers (A Book Apart) is a really approachable overview of this coding language. It is packed with practical examples that help to guide readers through their journey, and it has helped me get to know the essentials without headaches or unfriendly jargon. It’s a must for any coder.

Adrian Crookes, senior lecturer in communications and media, London College of Communication, University of the Arts London

Robert Cialdini, the master of persuasion, returns with a long-awaited sequel (prequel?) to 1984’s Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion, this time demonstrating the power of context in the persuasive process. In Pre-Suasion: A Revolutionary Way to Influence and Persuade (Random House), Cialdini collates an impressive array of studies suitable for academic and general readers. Part history, part memoir, Mark Thompson’s Enough Said: What’s Gone Wrong with the Language of Politics? (Bodley Head) is written with the flair of a journalist (obviously) and the rigour of an academic. He elegantly documents the battle for public language and in doing so provides a contextual framework for understanding recent political events.

Joanna Lewis, assistant professor in the department of international history, London School of Economics

Giacomo Macola’s The Gun in Central Africa: A History of Technology and Politics (Ohio University Press) is a methodological triumph. It offers a new history of pre-colonial Central Africa via meticulous research tracing the origins and destiny of European firearms into the region. This kind of scholarship is extremely challenging, but Macola’s command of language and local histories opens a new window on not just the Scramble for Africa but also the motivations of today’s militias in eastern Congo. “It’s raining men/Hallelujah/It’s raining men”: Alexandra Harris’ Weatherland: Writers and Artists under English Skies (Thames & Hudson) somehow fails to cite the Weather Girls’ 1980s hit, but what she has achieved through her scholarship will forever burn bright. Her history of how English culture has referenced the weather is beautifully written, stunningly evidenced and so well researched that she can make us feel the same cold felt by the Anglo-Saxons. And she can find deeper histories: “Though the twentieth century dreamed of brightness, it came to specialize in grey”.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Books of 2016

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?