“Most recently, ‘plain speaking’ has been cited by leave voters in post-referendum Britain as one of the defining features of ‘Englishness’,” notes Margaret Tudeau-Clayton about Brexit. The central hypothesis underlying Shakespeare’s Englishes is that discursive shifts both prompt and reflect changes in social institutions.

The emergence of English Protestantism required the formation of a new linguistic, economic and sartorial simplicity, which was to be – in opposition to the Catholic Continent – inimical to the flouncing effeminacy of everything foreign. Native plainness, Tudeau-Clayton writes, expressed “a shift of economic as well as cultural power from the court to non-elite educated men whose interests were served by the production of normative, stable linguistic and monetary systems”. That is, a new streamlined Englishness grew to define itself against an effete Anglo-Norman courtliness (rife with indulgent luxuriousness and corruption) as the economic and political clout of the middling sort emerged ever more strongly.

Here we see the origin of the myth peddled by populist politicians such as Nigel Farage, whose triumphant “English common sense” supposedly calls out the otiose and bureaucratically bloated Brussels. “Cultural reformation ideology” laced with xenophobia, as this book explains, sought to extirpate Latinisms and Romance loan words in favour of an Anglo-Saxon monosyllabic austerity. Tudeau-Clayton cites Thomas Wilson’s Arte of Rhetorique (1553): “we must of necessitee, banishe al such affected Rhetorique, and use altogether one maner of language.”

The book’s subtitle is “against Englishness” because Shakespeare, Tudeau-Clayton argues, undermines such homogenisation, preferring instead to fill his plays with a plethora of idiolects demonstrating an unlicensed “gallimaufry” (her term), a vibrantly confusing heteroglossia. His characters’ Englishes are “decentered, in a mobile, expanding, centrifugal mix” and, as such, subvert the drive towards logocentric inertia.

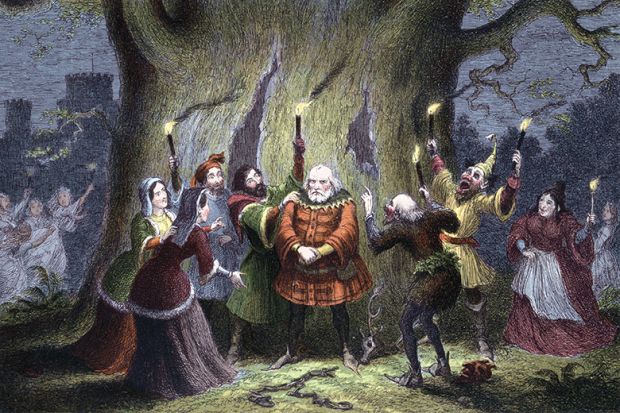

The early histories and comedies (notably The Merry Wives of Windsor) demonstrate a resistance to “the King’s English” and promulgate instead what Tudeau-Clayton describes as “linguistic practices [which] summon the energy or ‘quick’ of life”. Central here are (the suggestively named) Mistress Quickly and Falstaff, who both, by accident or design, speak in ways that tend towards “openness”, prodigality and all things “straing” (strange). This last term links to hospitality to outsiders or strangers. In one of Hand D’s contributions to Sir Thomas More – “now widely, if not universally recognised, as Shakespeare’s”, according to the author – the protagonist “seeks to ‘correct’ the popular perception of strangers as the origin of social evils”.

Tudeau-Clayton identifies the rejection of Falstaff as the moment of the arrival of “a modern bourgeois world of ‘true’ or ‘proper’ Englishness”. But, she points out, this brave new world permits Iago, Edmund and, in his wooing of the French Princess, Henry V to affect an unadorned plain style that turns out to be, in fact, nothing more than a Machiavellian cover for their deceptions.

This is a rich and dense book that sometimes stumbles into circularity and repetition: Crab (the dog in Two Gentlemen of Verona) is the hero of “a serio-comic parable/comedy of canine errors”, a blundering phrase repeated word for word 22 pages later. 1572 is identified as “the year of the St Bartholomew massacre, which saw a huge influx of French protestant refugees”; four pages below the sentence reappears. In a book about language, such linguistic infelicities need a more thorough purging.

Peter J. Smith is professor of Renaissance literature at Nottingham Trent University.

Shakespeare’s Englishes: Against Englishness

By Margaret Tudeau-Clayton

Cambridge University Press, 256pp, £22.99

ISBN 9781108725460

Published 30 September 2021

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?