At any mention of the Winter of Discontent of 1978-79, two images are sure to come to mind: rubbish piling up in the streets and the dead left unburied. A series of industrial disputes that challenged the Labour government’s policy of wage restraint culminated in widespread strike action in that winter. In May 1979, following a campaign that established the Winter of Discontent as a political touchstone, Margaret Thatcher led the Conservative Party to victory in the general election. The spectre of unemptied bins and unburied dead has been conjured up ever since – by Left as well as Right – as a cautionary tale about the destabilising effects of strike action and union power.

According to some studies, “memories” of the Winter of Discontent are paradoxically more pronounced among those born since 1979. Sociologist Tara Martin López sets out to describe how this “myth” was created and to explain its continued presence in British culture and politics. Along the way, she personalises the experience of that dramatic winter, drawing on material from oral interviews with rank-and-file trade unionists and shop stewards, as well as more high-profile figures including Rodney Bickerstaffe and political adviser Tom McNally.

There is no substantial reinterpretation of the political and industrial crisis here. When Martin reveals “a gulf between the Labour leadership and working-class communities” or suggests that James Callaghan as prime minister “showed a fatal rigidity in his dealings with the unions”, it is hard to be too surprised at these conclusions. Her oral histories add texture, while tending to confirm a picture already familiar from other accounts. What her study does achieve, however, is a greater focus on the employment conditions of some of the groups at the heart of the dispute. As one patriotic volunteer acknowledged when stepping into the shoes of striking auxiliary workers at a hospital: “It’s a stinking helluva job. I wouldn’t do it by choice or for their money.”

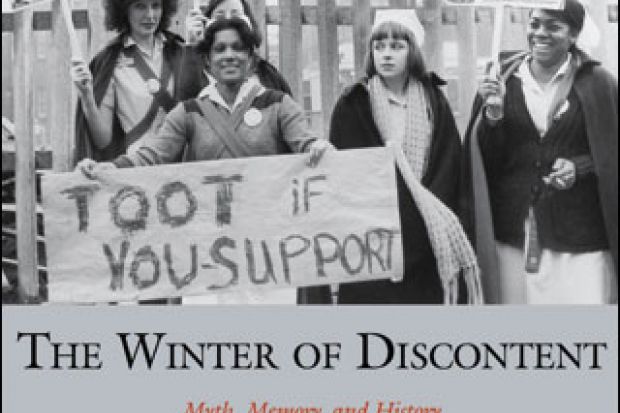

The fundamental cause of the strikes was wage levels. But the disputes throw light on many aspects of life in the workplace, and how the job market itself was changing. Expressions of alarm at the supposedly overweening power of the unions are particularly striking, given the low status of many of the workforces concerned. This was not about a labour aristocracy showing its muscle. Above all, the front line was now in public services. Several of the battles (particularly those concerning workers responsible for school meals, hospital laundry and cleaning) were notable for the numbers of women involved, highlighting the growing diversity of union membership and activism – all of which was on display in the events of that winter but was subsequently overshadowed in popular memory.

And finally there was the winter itself. The crisis (“what crisis?”) took place against a backdrop of unusually cold weather. As haulage strikes disrupted food and fuel supplies, pictures of the prime minister enjoying the sun in Barbados did nothing to improve the public mood. Political history does not generally pay much attention to the weather, but Martin suggests that this may have played an important part in dramatising the events and ensuring their lasting resonance. It’s a theme worth further consideration. Grim images of civilisation unravelling, coupled with dark days and arctic chill, all fed into the casting of the Winter of Discontent as a fairy tale for our times.

The Winter of Discontent: Myth, Memory, and History

By Tara Martin López

Liverpool University Press, 252pp, £70.00

ISBN 9781781380291

Published 24 July 2014

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login