Dealing with abuse after public commentary

Communicating to the public can result in abuse of academics. Here, University of Southampton staff describe their experiences and provide tips on anticipating and dealing with trolling

Research management

Sponsored by

Elsevier helps researchers and healthcare professionals advance science and improve health outcomes for the benefit of society.

Institutions are keen that their staff engage directly or indirectly with the public to improve knowledge transfer and provide informed viewpoints across topics of interest. The Covid-19 pandemic, for example, required continuous input and presentation of research findings from experts across a range of disciplines.

However, with contributions to public commentary comes the risk of abuse. This can be through replies to social media posts, emails to the individual’s inbox or in-person contact. Numerous experts have reported abuse when commenting on the pandemic, with regular commentators receiving the most abuse as their profile has increased.

We are three academics with a public profile, and a social media manager, at the University of Southampton, all with experience of receiving or dealing with cases of abuse or trolling. We organised an internal webinar in September 2023 to present to colleagues, and hear their views on this area, with the aim of improving awareness of support available and tips for dealing with unwarranted criticism (see Table 1).

- Five ways universities can protect faculty from online harassment

- How to prevent cyberbullying from rearing its ugly head in universities

- You’re not alone: tips to help academics avoid social isolation

The anti-vaccine lobby have long contributed streams of misinformation, along with abuse of and about individuals who aim to provide good-quality content about immunisation. Michael Head (a co-author of this article) is a regular writer on vaccine misinformation and has a regular stream of contact from “anti-vaxxers”, some of which is polite but wrong, and some of which is vile and abusive. Content can be racist, with references to vaccinations being equivalent to the Holocaust, and there are frequent accusations of genocide (their suggestion being that vaccines are killing people in large numbers – this is, of course, not remotely true).

In the past few years, discussions about the ethics of researcher safety – inclusive of mental and emotional health, and privacy and security online – have been increasing. This includes the mental and emotional well-being and self-care of researchers studying violent online phenomena, and the potential harms when disseminating findings publicly online. It is essential to consider the ethical responsibility of institutions, in both ensuring ethical conduct of research, and researcher safety.

When researchers are targeted with abuse and harassment

Researchers can be specifically targeted with strategic forms of abuse and harassment – often because of their identity (ethnicity, religion, gender or sexual identity, for example). These tactics are used to silence researchers who attackers may disagree with or who have been identified as “enemies”. Ashton Kingdon (co-author) has researched online extremism, radicalisation and terrorism for almost a decade. The nature of this work includes infiltrating white and male supremacist online communities, leaving her open to targeted attacks by bad actors, including networked harassment, doxing, violent personal threats (including rape and death threats) and offline abuse as a result of individuals turning up at speaking engagements she has advertised online.

Such campaigns can force researchers to stop using online platforms. Although the resulting disengagement is intended to be a solution to harm, it can have negative effects on researchers’ careers, given the increasingly important role of social media in connection to multiple audiences, developing collegial networks and building collaborations, as well as seeking funding and employment.

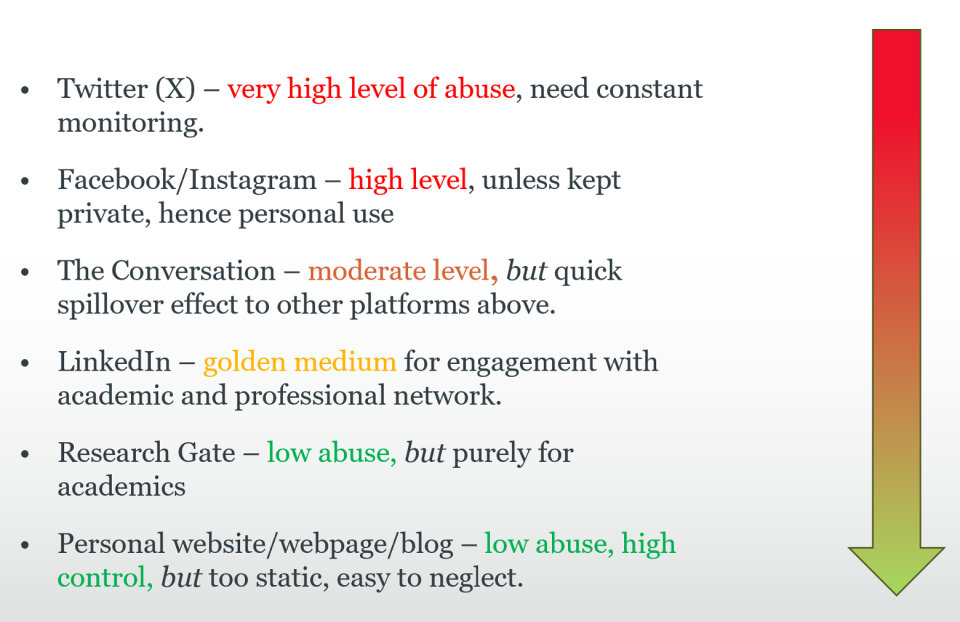

Female academics tend to receive offensive and condescending comments more frequently than their male counterparts from the same field. Larisa Yarovaya (co-author) is a regular commentator on cryptocurrency markets and has created a barometer that reflects our perspectives of where abuse is highest and lowest (see Figure 2). The crypto industry relies heavily on its media presence, with social media platforms such as X (formerly Twitter) often serving as the primary communication channel with investors and the community. Consequently, public criticism is not always well received. Factors such as gender, and even physical disabilities, can be used in trolling, making these comments particularly hurtful.

created by Larisa Yarovaya, University of Southampton

Institutional awareness of these issues can be limited, in large part because of the relatively recent advent of online research, and the quickly changing pace of online phenomena and practices. Occupational supports, essentially workplace accommodations, that are needed to address the impacts of such research include institutionally provided access to specialised trauma counselling, specific hardware and software to support safe research online, legal support in cases of networked harassment and online threats, and mechanisms to request extensions to research time frames or career milestones.

| Work on building your confidence through your expertise and knowledge – this may make it a little easier to ignore non-constructive criticism. |

| Ignore and/or block those users. Remember – you don’t owe them anything, so don’t be afraid to block those who are not arguing reasonably or in good faith. |

| Typically, don’t reply directly to the troll (their views are entrenched, they’ll happily lie/move the goalposts). If you have the energy and enthusiasm, you can counter their viewpoints for the benefit of the silent majority. |

| Build a supportive, positive network of fellow experts and colleagues, who can help counter any unfair negativity. |

| Step away from social media, and mute notifications (especially if there’s a “pile-on” from conspiracy theory-fuelled accounts). |

| Comment instead on a different platform (for example, LinkedIn instead of X/Twitter). |

| Reach out to your institutional social media or media relations colleagues, line manager or HR. And if you feel genuinely threatened, consider whether you need to seek legal advice through your institution or report to the police. |

| Consider which platforms you wish to communicate with. For example, if commenting on extreme individuals, being named on mainstream news (which significantly raises your profile) may not be beneficial. Also, consider being anonymous in news articles. |

| Ultimately, look after yourself. Develop self-care approaches that help you relax and clear your mind. There is no shame in seeking support from mental health professionals if the experience of bullying becomes overwhelming. |

Table 1: Tips for managing or pre-empting abuse

How individual academics can respond to online trolling

At an individual level, if you find yourself on the receiving end of excessive negativity and are facing online trolling, here are key actions to consider.

- First, remember that trolls aren’t interested in honest debate and they’re not looking to be converted. Ignoring them can be effective, so try not to feed their attention-seeking behaviour by engaging.

- If notifications become overwhelming, turning off app alerts is a sensible choice. For persistent trolls, immediate blocking prevents further contact or mentions. If you feel overwhelmed, temporarily tightening your privacy settings can provide respite.

- In cases of defamatory or criminal content, record it with screenshots and report it directly on the platform. However, if a comment is a potential criminal issue, seek guidance on reporting to the police or consult your university’s legal team.

- Don’t forget that you’re not alone. Reach out to your line manager or your university’s media and social media teams for support. They should be able to help navigate these challenges and ensure that academics can continue to share their research and expertise with a wider audience.

Universities do have a duty of care towards their staff. However, staff may lack awareness of any institutional advice or guidance around managing content in the media or on social media. The guidance may be inaccessible or hard to find. It can also be out of date, with social media platforms evolving, and thus the risks of abuse changing rapidly, for example, on X (formerly known as Twitter).

University assessment exercises, such as the Research Excellence Framework, and the thirst for expert knowledge around issues such as climate change or pandemics, show an ongoing need for university staff to speak out. Our efforts provide a starting point for raising this awareness, highlighting examples of good practice, and giving university staff tools and confidence to deal with adverse consequences when engaging in public commentary.

Michael Head is senior research fellow in global health in the Faculty of Medicine; Larisa Yarovaya is associate professor of finance and director of the Centre for Digital Finance at Southampton Business School; Ashton Kingdon is lecturer in criminology; and Millie Downer is social media and engagement manager. All are at the University of Southampton.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.

Research management

Sponsored by