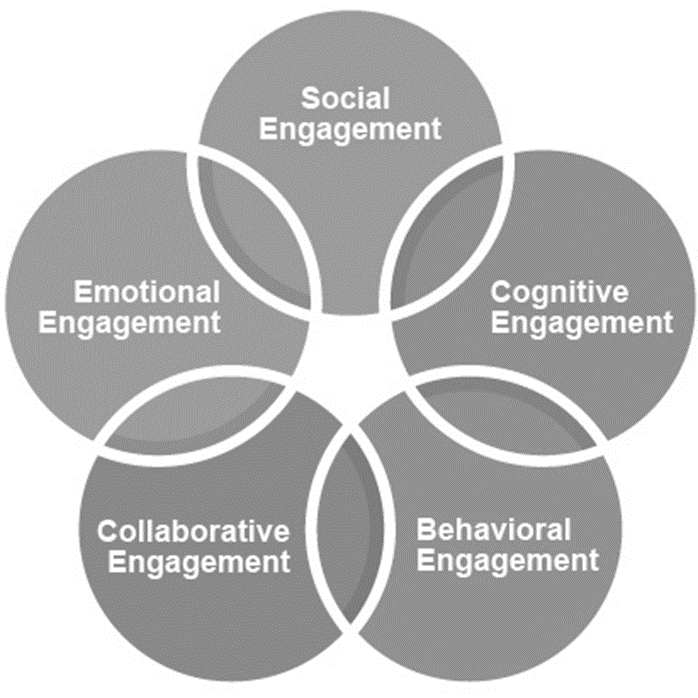

Five key elements that drive student online engagement

Student engagement is extensively acknowledged in educational literature as correlating to student learning, success, motivation and retention. The physical and psychological energy that the students invest in the academic experience largely drives their experience of online learning because, ultimately, it is up to them how much they engage in the learning process and how much they get out of it.

In 2018, academics from the University of Southern Queensland recognised that engagement rested on five key elements (social, cognitive, behavioural, collaborative and emotional). They proposed a framework (see below) that is still useful for online higher education teachers, learning designers and trainers in building strategies to improve online student engagement.

(Redmond, Heffernan, Abawi, Brown and Henderson, 2018)

Using the online engagement framework to support student learning

The online engagement framework can provide a structure for online educators to promote different types of student engagement through social, cognitive, behavioural, collaborative and emotional elements, as recognised by its creators.

This article provides practical teaching and learning considerations for online educators based on these five factors.

Social engagement

Imperative to student success in an online environment is social connectedness. These types of activities are understood to foster social engagement within a learning community and include opportunities for students to discuss the learning materials, as well as instances where students can create important and mutually beneficial relationships with both other students and the teaching team, perhaps in the same way they might do on campus.

- What I learned from spending three years researching TikTok

- Collection: Higher education goes hybrid

- Successful classroom discussions begin long before anyone speaks

Social engagement and interaction can be encouraged online through targeted discussion forums. These interactions can also increase students’ sense of belonging to a group of learners. In addition, social forums and synchronous video conferences can be spaces where students can feel supported, discuss the challenges they are facing, develop deeper connections with the teaching staff and the larger university or learning institution.

Social engagement can be facilitated simply, by asking students to share their names, favourite films, photos of their pets, or why they chose to undertake a particular subject or course.

Finally, direct synchronous communication and teacher-led events, which incorporate group work, breakout-room activities, debates and sharing learning, facilitate social engagement and peer-to-peer learning.

Cognitive engagement

Cognitive engagement is a fundamental form of engagement, as it addresses a student’s ability to comprehend complex ideas and master difficult skills. Activities that heighten cognitive engagement often challenge students’ preconceived ideas on a given topic or problem, inviting them to rationalise any cognitive dissonance either by themselves or through conversation with others.

Cognitive engagement within the online environment can be facilitated through critical-thinking activities such as reflection, justification activities or learning tasks that ask students to compare ideas and identify solutions. In addition, learning interesting and personally and professionally relevant content that is current and transferable to other contexts will also enable cognitive engagement.

Cognitive engagement can also be enabled through the careful, considered means in which instructional design and sequencing of online learning content are managed. This includes providing sufficient scaffolding and balance, so learners remain cognitively involved but not overwhelmed or distracted due to excessively difficult, redundant or repetitive content.

Behavioural engagement

Behavioural engagement has been described as behaviour where learners demonstrate ways of working that follow explicit expectations. This includes adherence to a set of behaviours, rules and norms, such as active engagement with discussion boards and active participation in learning activities. For teachers, clarifying acceptable online behaviour, as well as appropriate levels and frequency of engagement, allows students to respectfully question, challenge and communicate with teaching staff and peers.

When expectations of behaviour have been clearly and explicitly stated, students are more likely to develop their professional identity and the conventions and norms essential in any professional community. Therefore, educators must clearly state the behavioural expectations associated with contributing to discussion forums.

Online educators should model supportive and positive behaviour and affirm positive behaviours of engagement.

Collaborative engagement

Despite the geographical distance, online students are more likely to be engaged when they can collaborate in discussions, debates and undertake group assessment tasks. Collaborative engagement can include designing authentic assessment activities, work placements, internships, career festivals, networking events and other formal/informal professional activities.

Collaborative engagement complements social engagement, and collaborative engagement is easier to enable if the other engagement elements are addressed. For example, online multimedia or other technological interactive activities could allow students to appreciate the backgrounds of the broader group or see scenarios through the eyes of others.

Collaborative engagement is also related to students’ connection to the university as a whole. This can be promoted through participating in university committees as student representatives, university teams, or societies. Collaborative engagement also considers how students begin interacting with the profession/industry in which they are gaining qualifications. This can be achieved through student membership of relevant industry professional associations, attending conferences or gaining industry mentors.

Emotional engagement

Harnessing the emotions of learners has the potential to increase a particular type of engagement and connection to online learning. Emotional engagement includes the positive or negative attitudes and feelings that students connect to their learning. This may be responses to content, peers, contexts or educators.

Supporting online learners to regulate their emotions across the learning process when engaging with new or difficult concepts is critical from the outset. Not managing emotional engagement across the student cohort could result in the teacher triggering adverse or negative reactions to the learning content or teaching interventions.

Strategies that can increase student emotional engagement can include using polling activities and allowing students to self-direct and check their own understanding of the subject matter. These examples can greatly assist student ownership and motivation. Likewise, discussion forums allow learners to post uncertainties and use the expertise of their peers to help provide a little more clarity.

Moving beyond ‘talking at’ students

While the traditional approach to teaching in higher education and at workplace training events is to “talk at” students, greater scrutiny is being applied, as it should be, to the effectiveness of this paradigm on student engagement and learning. The five elements of Redmond et al’s (2018) online engagement framework provide clear guidance for educators new to managing student engagement and learning online and a guide for online instructional design. The framework offers a way of organising online student engagement activities and teaching more purposefully. Importantly, it provides a tool to reflect on current and future online teaching practices.

Jay Cohen is associate professor and deputy director of Online Education Services – Education Services at La Trobe University. Alice Brown is senior lecturer in early childhood education and Petrea Redmond is a professor of educational technology, both at the School of Education at University of Southern Queensland.

The following authors also contributed to this article: Rakesh Patel is associate professor in the School of Medicine in the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences at the University of Nottingham. Stephanie Foote is associate vice-president for teaching, learning and evidence-based practices at the John N. Gardner Institute of Excellence in Undergraduate Education at Stony Brook University. Jill Lawrence is head of school and dean of the School of Humanities and Communication at the University of Southern Queensland.

If you found this interesting and want advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the THE Campus newsletter.