Full circle: using the cycle of teaching, module design and research

Since moving into leadership roles, my time in the classroom has been limited and, as a result, has become more precious than ever. Those hours that are just me and the students, sans emails and spreadsheets, are the highlights of my week (apologies to the emailers and spreadsheet designers).

For someone like me, practiced in the “skill” of overthinking, less teaching also means more time to analyse the teaching I do undertake. And this is the reason for this post: my critical brain turning in on itself, stripping everything away and exploring, for the first time in many years, why I make the decisions I make both in preparation for and during my classes.

Here goes.

The circle of teaching and research

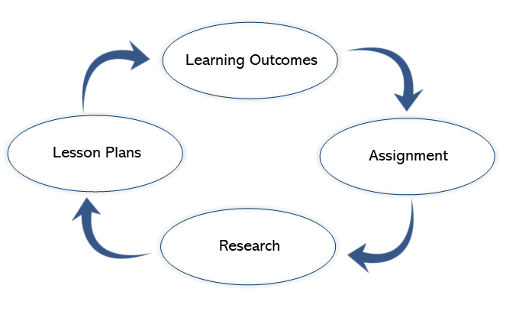

For me, the process of module design always involves working in a circular way (see graphic below), beginning with the learning outcomes. These then inform what can be assessed via the assignment, which informs the aspects of my research I need to draw upon. These aspects are used to design the lesson plans, which are checked against the learning outcomes to ensure the students are getting the information they need to write their assignments. The students are prepared for these assignments via the lesson content, through which the students achieve the learning outcomes. Phew. (The visual below is for myself more than anything!)

Every good post deserves a case study

As this post needs a case study to reinforce its points, and as I only taught on one module anyway last semester, I’m going to draw upon Composing Song Lyrics, a second-year undergraduate module. In this module, the learning outcomes demanded that students: a) present their own creative and critical interpretations of a song; b) have an extended knowledge of a range of songwriting forms across history in order to be aware of fundamental techniques of songwriting; c) demonstrate the impact on their learning of their full engagement with the taught element of the module; and d) explore the roles of race and gender within song lyrics (UN Sustainable Development Goals 5 and 10).

- The power of gender-sensitive mentoring

- Ten ways universities can tackle gender inequality

- Managing excluding behaviour and bigotry in the classroom

With the University of Winchester having a single assessment structure, ensuring that the creative and critical learning outcomes were assessed in a natural way necessitated a portfolio assignment, which was presented to the students as: a creative submission (a selection of song lyrics) equivalent to 2,000 words and a 1,500-word essay.

The essay portion was further broken down as: a 1,500 word critical analysis of an album, including discussion of race and gender within the lyrics and wider music industry.

The essay allowed elements of all four learning outcomes to be assessed, with the remaining parts assessed during the creative portion of the portfolio. At our university, in our assessment regulations, we have grading descriptors at each level, with Level 5’s stating that students will be graded on academic skills; subject knowledge and understanding; research and enquiry; values, qualities and attributes; and applied and practical skills.

How does research inform teaching in creative fields?

It was now time to revisit my research, to see which aspects I needed to draw upon to ensure the students were getting the information necessary to meet these regulations.

(Slight awkwardly self-congratulating yet still relevant) sidebar: 2022 was a year of intensive writing for me, where I published three books, got contracts for a further three, and had the usual smattering of chapters, conferences and articles thrown in for good measure.

As my own writing projects almost exclusively focused on the critical study of song lyrics and I was also teaching on the Level 5 module Composing Song Lyrics, it was inevitable (and perhaps necessary) that my research would bleed into the lesson and assignment content.

But although there was obvious crossover between what I was writing and what the students needed to learn to be able to write their assignments (more on that shortly), as this module followed the classic BA in creative writing way of observing before doing, we began with the critical content weeks before they started writing their own lyrics.

I co-teach this module with professional songwriter Daniel Ash, who takes the creative side of things (more on our team-teaching approach here), so with two dedicated workshopping weeks at the end of the module, and Daniel taking his five classes, I had only five lessons at my disposal, which would then need to feed into the critical assignment. Add to that the fact I had written nearly 200,000 words of content that was relevant to the module (not to mention another 100,000-odd from previous books/chapters) and I had my work cut out to make sure the students had everything they needed, but not give them so much that they were overwhelmed.

Lesson outline examples

My five lessons on the critical side of the portfolio assessment ran as follows (with the research from which the lesson plans were constructed appearing in parentheses):

- Linguistics and song: perspective, tenses, metaphor, simile, symbolism, alliteration (Reading Eminem by Glenn Fosbraey [Palgrave Macmillan, 2022], Section 4: “Eminem and language”)

- The art of persuasion: how songwriters can elicit emotional connections via the use of rhetorical devices (Writing Song Lyrics: Creative and Critical Approaches by Glenn Fosbraey and Andrew Melrose [Palgrave Macmillan. 2019], Chapter 7: “Persuasion and emotion”)

- Lyrics and the internal/lyrics and the external, including the importance (or lack of) of an artist’s biography on a song (Viva Hate: An Exploration of Hatred in Popular Music by Glenn Fosbraey [Cambridge Scholars Press, 2022], Section 3, and my chapter, “Manipulation and truth in The Final Cut”, in The Routledge Handbook of Pink Floyd, edited by Chris Hart and Simon A. Morrison [Routledge, 2022])

- To rhyme or not to rhyme? Different rhyme types and sequences, and their impact on a song (Reading Eminem, Section 1: “Lyrics vs poetry”)

- Considering the performative, technological, visual, socio-cultural and political aspects of song (Misogyny, Toxic Masculinity, and Heteronormativity in Post-2000 Popular Music, edited by Glenn Fosbraey and Nicola Puckey.P[algrave Macmillan. 2021], Chapter 2: “…Featuring Nicki Minaj”)

And then back to the learning outcomes, and checking the assignment etc, etc…

A final note

I firmly believe that to keep progressing as tutors, and to ensure we’re not short-changing our students out of best practice (not to mention our best selves), self-analysis is not only beneficial but essential. Just think: if it wasn’t for me spending too much time looking inward, I wouldn’t have that fantastic flow chart to show off.

Glenn Fosbraey is associate dean of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences at the University of Winchester.

If you found this interesting and want advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the THE Campus newsletter.