A guide to supporting student parents at university: part two

The second in a three-part series provides detailed, practical guidance on how student parents can be supported to succeed at UK universities

You may also like

Popular resources

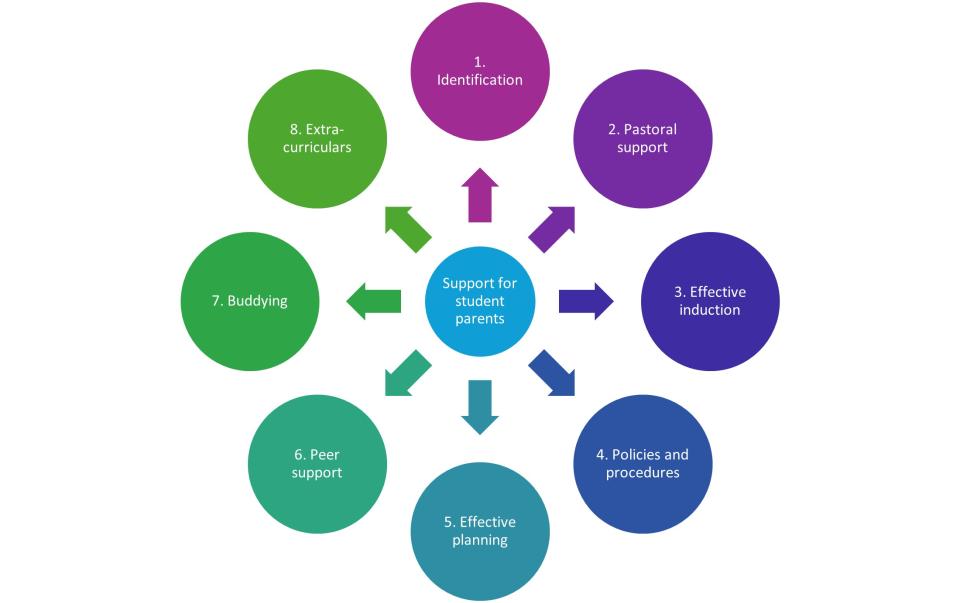

My Eight Steps to Identifying, Supporting and Celebrating Student parents toolkit does what it says on the tin. Designed as an easy-to-pick-up document for a range of readers from programme leaders to department and faculty leaders and senior management teams, it sets out eight research-informed steps to establishing appropriate and tailored support for student parents. Each of the steps contains practical tips on how providers and/or individual departments can achieve the aim set out. These are summarised below.

Step 1: identify the cohort

This step recommends that providers use their own data-gathering methods to determine which of their students are parents, such as pre-arrival questionnaires and the inclusion of a question regarding parental status in re-enrolment surveys between academic years. I wrote the first iteration of this prior to Ucas’ inclusion of the student parent question in its application form (and before the Office for Students included student parents in their Equality of Opportunity Risk Register). Even following the introduction of the Ucas student parent question, this step remains important for two reasons:

- There will always be students who choose not to self-identify via Ucas (indeed, the national study revealed that while 93% believe it important for providers to know who their student parents are, only 85% would have identified themselves via Ucas because of concerns about how the information would be used);

- Individuals may become parents between their application and starting university, and indeed while at university.

Step 2: equip personal tutors

Both research projects revealed that, in general, personal tutors were not sufficiently informed about how to provide appropriate support to their student parents The recommendations in the toolkit seek to ameliorate this, including allocating student parents to defined individuals who volunteer to take on the role of personal tutor to student parents. It is crucial that the data identifying those with parental responsibility filters down from data teams to faculties and departments to facilitate appropriate support. Institutions can facilitate this by requiring that the data set passed to teams responsible for the allocation of personal tutors to students includes a field to flag parental responsibility.

Step 3: provide effective induction

This step provides tips on easing student parents into university by way of pre-induction communication, for example via email or messages via the institution’s pre-arrival website. I also provide recommendations for tailored induction sessions covering issues such as how students plan to balance study and family life and an early introduction to university policies. These include the rules relating to timetable change requests to facilitate childcare needs and the extenuating circumstances process (where the student’s child, rather than the student themself, falls ill).

- Resource collection: how to factor family into higher education

- Supporting parent academics through staff networks

- Childcare for students and academics needs resources and relationships

Step 4: amend and, where possible, clarify policies and procedures

In both research studies, inflexible exceptional circumstances policies were cited as barriers to student-parent success, notably the evidential issues caused by child illness which interfere with the student parent’s ability to complete assessments. The provider-level recommendation to consider an exemption for childcare-related reasons is a longer-term goal given the speed at which institutional policy machinery operates, but this step also queries whether departments can take local action within existing regulations to exercise discretion in this regard.

On a related note, it is worth providers exploring alternative assessment structures that obviate the need to make use of mitigating circumstances policies, for example, moving away from exam hall and/or time-released assessments or operating a “submission window” rather than deadline on a specific time and date.

Step 5: facilitate effective planning

A very strong theme across both research projects was the time poverty experienced by student parents. The national survey respondents flagged the need for practical assistance with time planning (this is addressed by way of detailed guidance in The Student Parent’s Guide to Navigating University and The Personal Tutor’s Guide to Supporting Student Parents). This step also provides advice on how student parent participation in learning sessions can be maximised by way of recorded didactic sessions and early release of draft timetables. Some providers (such as the Law School at the University of Chester) release draft timetables and invite students to express preferred seminar sets prior to allocating students across the available sessions. This can not only ameliorate childcare challenges but also assist those with other personal or work responsibilities outside their studies.

Step 6: establish a peer support group

The first research study showed that online peer support groups are effective, with 100% of students involved in a pilot group reporting that membership of the group was helpful to them, referencing the sense of belonging and reassurance that this shared experience brought. This can be set up very simply on Teams or a similar platform by student services teams or by a team member at the departmental level. Some institutions may opt for both the institutional and local approach.

Step 7: provide mentoring

Student parents in both research studies reported having considered giving up on their studies. A mentoring/buddying system between students across year groups may assist with the transition into university and the transition (and retention) between academic years. Again, this can be a formal arrangement managed by central student services teams or it can be arranged on a less formal basis by the member of staff responsible for student parent peer support group at the departmental level. It would involve them simply putting new student parents in touch with those further along in their studies who have agreed to meet their new student parent peers for coffee to help them settle in.

Step 8: provide equitable opportunities

Both research studies highlighted childcare as a barrier to effective participation in CV-building extra-curricular activities and in careers events that can assist in securing employment. This step provides practical tips as to how providers, departments and careers teams can level the playing field for student parents to enable them to participate effectively in such activities and events. This includes, for example, not just recording evening careers events (inaccessible for many parents because of childcare) but, wherever possible, live-streaming them to enable student parents to be actively involved in the event. Where extracurricular activities can be ring-fenced (for example, can be done between 10am and 2pm), this should be advertised to encourage student-parent participation.

If you missed them, read part one and three of this series, or, for more details and an induction, you can access the full toolkit here.

Andy Todd is associate professor of active citizenship at the University of Chester.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.

Comments (0)

or in order to add a comment