Guide learning by activating students’ inner feedback

David Nicol explains how students can be guided to make comparisons and feedback on their own work, rather than relying on instructor comments, for improved learning outcomes

You may also like

Popular resources

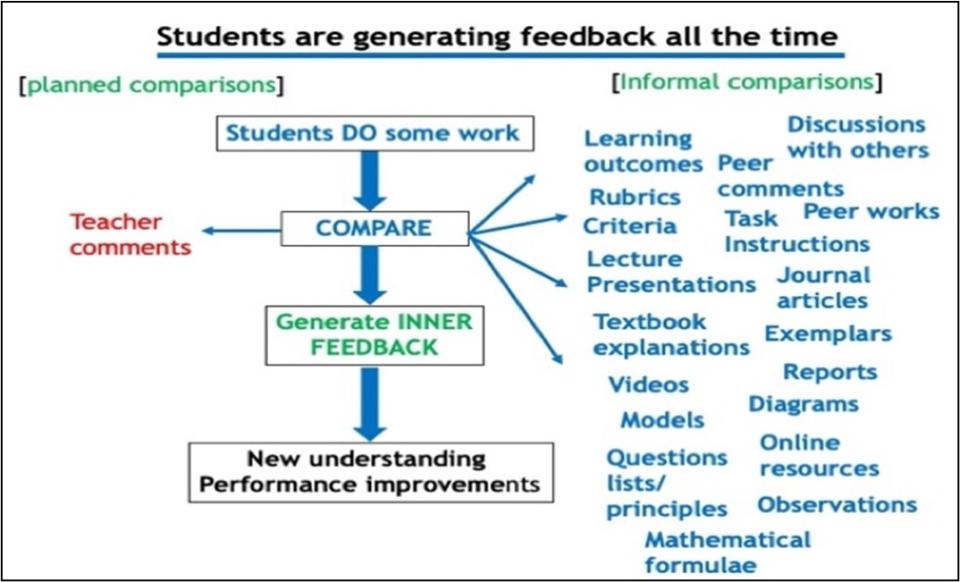

Normally when we think about feedback, we think about comments that lecturers provide to students about their work. However, to learn from these comments students must compare them against their work and generate new knowledge and understanding out of that comparison. In this view, comments comprise information that activates internal feedback processes.

But what if students compare their work against other types of information, for example, a video or a journal article? Research at the Adam Smith Business School shows that in many cases students generate better feedback, ideas for improvement, than they generate from received comments.

We all learn by generating feedback. We compare our own performance against information from many sources, from books to observation of others, and we generate inner feedback out of those comparisons.

As students produce an essay or solve a complex mathematical problem, they might go online and use resources they find to improve their work before its submission. This involves a comparison. Making such feedback comparisons is a natural, ongoing, pervasive and cyclical process that underpins learning.

Figure 1: Information that students might naturally use for comparison (right side) and the information that dominates current teaching (left side)

Yet in higher education, instructor comments seem to be the only comparator that we plan for, albeit implicitly. Comments are seen as feedback rather than as information that generates feedback. Hence lecturers take responsibility for feedback provision and students relinquish agency over their own feedback processes.

- A guide to effective online assessment design

- Resources exploring how to use failure to support learning

- How immediate feedback motivates both students and educators

How to unlock the potential of inner feedback?

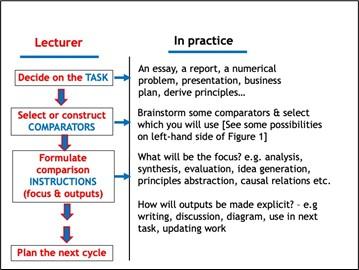

The key is to tap into and build on students’ natural feedback capacity. This means having students make deliberate comparisons of their work against information from sources other than comments, and to make the outputs of those comparisons explicit in writing, discussion or action.

The sequence for students is: DO work, make some COMPARISONS and make outputs EXPLICIT.

The lecturer needs to facilitate feedback comparison opportunities by guiding students in the focus and outputs of their comparisons:

Figure 2: The iterative design steps for implementing comparison-based inner feedback

Practical examples

An online lecture

Traditionally, a lecturer might deliver a lecture segment, have students engage in an activity and then continue with the lecture. In this scenario, students naturally make comparisons with what they have done and the subsequent lecture content.

To harness inner feedback, after the activity, the lecturer can ask students to listen to the next lecture segment and update what they produced in that activity based on their comparison with new information. Or to write down what they learned or the questions it raised for them. Going further, they might discuss their learning with peers, thereby activating another comparison process, with the thinking of peers.

A video or a journal article

A student writes a draft report then watches a video interview of an expert discussing issues relevant to the report. The lecturer asks the student to write down what they learned from that video or, specifically, to write down what they learned about the “analysis” in their report from the video. The lecturer could also use relevant journal articles as comparators.

Zoom breakout groups

Students working on a group project in breakout rooms are often asked to come back and present to the class. This is a natural comparison opportunity.

To capitalise on it, the lecturer can ask students, as they listen to each presentation, to think about what their group produced and write down what could be improved. Or students might listen to all the presentations and be asked to derive the common recommendations, which are usually the most powerful. This comparison supports the transfer of learning to new contexts.

Individuals might take their ideas back to their group and compare and discuss them before jointly updating the report, thereby activating another dialogical comparison.

A rubric and assessment criteria

Have students complete a task, then compare what they have produced against the rubric or assessment criteria provided and submit an analysis of this. Knowing that this is a requirement will ensure that students make deliberate comparisons throughout production of their work.

Why is all this important?

- It connects formal and informal feedback processes in mutually powerful ways.

- It uses multiple information sources beyond comments.

- It reduces lecturers’ feedback commenting workload.

- Making comparisons explicit builds students’ own feedback capability, metacognitive knowledge and ability to regulate their own learning

- For teachers, it provides valuable information about what comments students really need.

Top tips

- Plan the DO and COMPARE sequence to open up new feedback opportunities.

- Use the INSTRUCTIONS to focus comparisons towards desired learning outcomes, help students grasp complex ideas, address difficult concepts and skills, generate creative thinking and develop important graduate attributes.

- Stage and vary the comparison information across the course. The more comparisons students make, the more they build their own feedback and learn. Different comparators generate different kinds of feedback.

- In planning, start with material comparisons such as documents, videos and observations, then amplify with peer comparisons. This goes way beyond peer learning or peer review.

- Use comments sparingly, after other comparisons, and resist commenting on comparisons you ask students make. Where possible, stage another comparison.

- Over time, have students select feedback comparison resources for each other.

There is a big difference between telling students to go and look at an article or an online resource and asking them to make a deliberate comparison and to make the outputs explicit.

Reframing feedback as a comparison process engages and positions students as agents of their own learning. Evidence shows grade increases without any teacher input as comments. It is practical and easy to implement as comparisons are already happening everywhere, it is just about harnessing them. It simply requires a shift in mindset. The best advice I can give is: try it yourself and see!

David Nicol is a research professor in the Adam Smith Business School at the University of Glasgow.

This advice is based upon his research paper: The power of internal feedback: exploiting natural comparison processes.

Additional Links

Watch David Nicol outlining how the power of student internal feedback improves grades.

Read David's research on "The power of internal feedback: exploiting natural comparison processes".

Comments (2)

or in order to add a comment