How to unpick sustainability reporting in your business teaching

Increasing concern with how corporate activity interacts with environmental and societal development has led to a rise in sustainability reporting since the 1990s. Until recently, companies have been able to pick, choose or ignore several voluntary sustainability reporting frameworks and standards that seek to highlight how socio-ecological development might affect or be affected by their activity. Sustainability reporting has therefore remained on the margins of corporate reporting subject to concerns about greenwashing and irrelevance. However, as recent developments look to mandate new forms of sustainability reporting across the EU, the UK and elsewhere, this article offers ways to help students distinguish and evaluate how sustainability is translated within different international reporting standards.

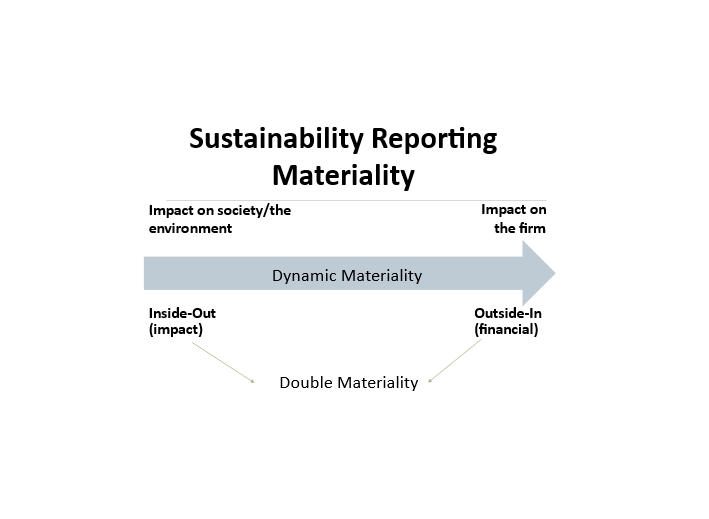

As a starting point, one can ask students to look at specific sustainability reports published by large companies and ask them to identify the focus of the reports on a spectrum between two poles: are the reports focusing on the sustainability of the planet; or are they focusing on the sustainability of the company? We can then ask them to explain or justify their choices, and thereby critically explore the interactions between those different translations of sustainability. For example, the tension between seeing corporate activity as a cause of (harmful) socio-ecological change and as a source of innovation and economic value that can be used to address socio-ecological challenges.

After sufficient discussion, we can then introduce the differing conceptions of materiality that are used to distinguish the poles in sustainability reporting and inform what type of sustainability information companies should disclose to the markets and society.

Sustainability reports focused on the sustainability of the planet use an inside-out conception of materiality that requires companies to report on how their activity materially affects the environment, society, the economy and human rights. Information is reported based on its impact on the planet (impact materiality), rather than its financial impact on the firm.

- Resources for higher education professionals on the sustainable development goals

- How to implement experiential learning into accounting education

- Sustainability accounting is coming: here’s how to navigate it

Sustainability reports focused on the sustainability of the company use an outside-in conception of materiality that requires companies to report only on those social and environmental issues that are deemed by management to materially affect the decisions investors make about the future value of the firm. In doing so, the standards seek to reorientate flows of financial capital to those firms that can show they are less affected by climate change, water stress, biodiversity loss and societal upheaval and those that might thrive by offering solutions to socio-ecological challenges.

As these outside-in standards focus only on reporting socio-ecological issues that are financially material, they look to tweak rather than revolutionise current notions of corporate success by seeking to extend the time horizon over which success is measured and highlight those socio-ecological factors upon which future corporate success depends.

After introducing the different approaches to sustainability reporting, classroom debates can help to identify inside-out reporting information and consider when or whether it is likely to become material from an outside-in perspective.

Teaching examples

| Inside-out reporting: impact on the environment, the economy, society and human rights | Issue | Outside-in reporting: impact on the firm |

| Climate change | Carbon emissions | Costs arising from mitigation plans, and tax/regulation required to meet international agreements |

| Agricultural monoculture (e.g. palm oil, soya bean, forestry) leads to material biodiversity loss | Biodiversity | Biodiversity loss lowers yields for producers and increases input prices |

| Short lead times perpetuate the abuse of labour rights | Supply chain subcontracting | Regulatory and reputational costs if discovered |

| Material freshwater usage in water-stressed areas | Water usage | Costs if water usage becomes subject to tax/regulation |

| Plastic packaging causes microplastic pollution | Packaging | Costs if packaging materials become subject to tax/regulation, or lead to a fall in customer demand |

| Opening a new manufacturing facility in a region of high unemployment leads to job creation and training | Employment and community development | Benefits if the region offers cheaper employment and training costs |

In thinking about the relations between the left and right columns in the table, we can introduce the notion of dynamic materiality, which recognises that issues that might only be material from an inside-out perspective can also become material from an outside-in perspective over time. For example, while carbon emissions would be considered material from an inside-out perspective in the 1980s, management might consider they would have no material impact on expectations of corporate value. Since then, international agreements and the advent of emissions trading schemes lead carbon emissions to be financially material from an outside-in perspective.

Finally, one can introduce the new standards that learners will probably be interacting with in the future. For example, the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) has developed standards based on an outside-in vision of reporting. A contrasting approach, led by the long-standing Global Reporting Initiative’s Global Sustainability Standards Board (GRI/GSSB) offers a more expansive vision and a more radical shift in the notion of corporate success. The middle ground, encompassing both materiality perspectives (so called double materiality), offered by the European Sustainability Reporting Standards, is being implemented across the EU.

As sustainability reporting moves from the periphery to the mainstream and becomes embedded across curricula rather than being treated as an adjunct add-on, the materials offer some ideas of the ways to distinguish and appraise the ways in which sustainability is translated.

Nick Rowbottom is a professor at Birmingham Business School, University of Birmingham.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.