The hows and whys of improved interactions with international students

You may also like

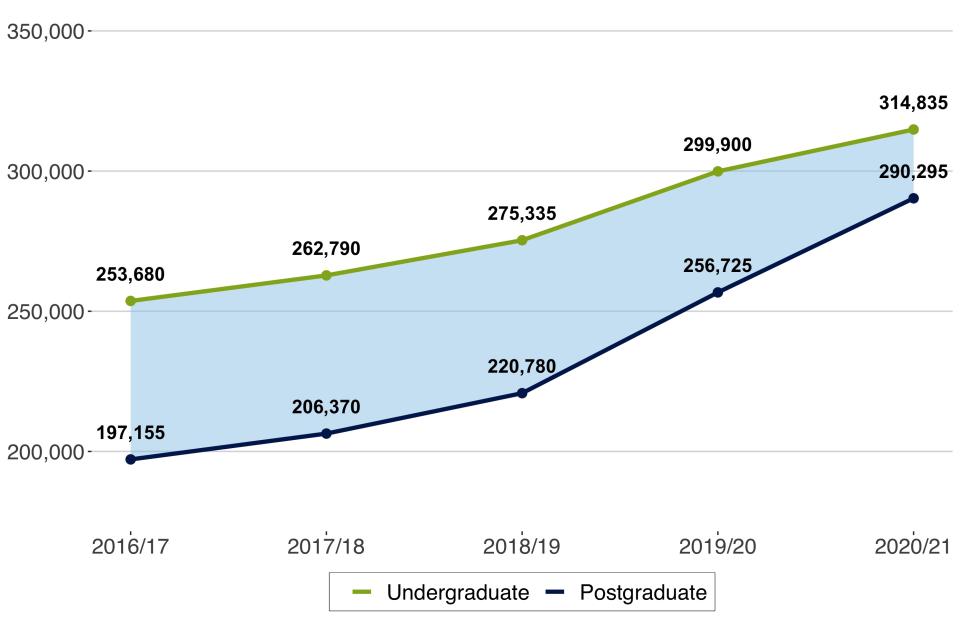

The number of international students in the UK continues to grow. This is especially true for non-European Union countries, with China (99,160 students enrolled in 2021/22), India (53,015 students) and Nigeria (14,270 students) leading the statistics.

A 14.5 per cent annual growth in non-EU postgraduate student numbers in the UK between 2020/21 and 2021/22 meant they represented 54 per cent of non-EU international students enrolled in UK institutions in 2021/22, according to the Higher Education Statistics Authority.

Due to cultural differences, studying at a foreign university can be emotionally, socially and academically challenging. There is no doubt that emotional and social experiences are critical; however, this piece focuses on the academic aspect, more specifically on international students’ interactions with academics.

- Resource collection: New approaches to the internationalisation of higher education

- Breaking language barriers: supporting non-native English-speaking students

- Peer review in multilingual classes

One reason for this focus is that academic-student interactions impact the social and emotional well-being of both. Uncovering cross-cultural differences could improve the understanding of students’ and academics’ pedagogical expectations. Another reason is my unique position as a former international student and now an early career academic in the UK. I draw on my personal and professional reflections from transitioning between these roles.

Participation and engagement: ‘I need to have the right answer’ v ‘I’d like to see you engaged’

Some of the most visible differences observed between international and UK-based students is their level of engagement in lectures and supervisions. While international students arrive at every lecture, they have the tendency to be the quieter group. To overcome their reluctance to participate, you can:

- Encourage students’ participation by openly stating that there are no right or wrong answers.

- Explicitly invite students to contradict the presented ideas. Explain that questioning what they learn shows their engagement with the topic.

- Calling out students personally could help but academics should be confident that the selected student does not have language barriers. Otherwise, a student may lose face and the effect will be the opposite.

Bloom’s taxonomy partially explains differences in participation and engagement expectations. The taxonomy outlines learning objectives in the shape of pyramid. The bottom layer represents “remembering” or knowledge recall. Learning objectives move up the pyramid through the stages of understanding or explaining concepts, applying knowledge in new situations, analysing ideas, evaluating concepts, up to finally creating new knowledge. In many Eastern cultures, the bottom level of reproducing knowledge is the educational aim, with academics being the “knowledge providers” and students “knowledge receivers”. In the West, education emphasises higher taxonomy levels such as deeper understanding and students’ self-discovery of knowledge, their own skills and potential. Since many international students have not experienced Western education prior to arriving in the UK, they may not realise their participation is expected or know how to actively engage.

Instructional language: ‘Tell me what to do exactly’ v ‘Think independently and be creative’

For students coming from more directive cultures, vague language of instruction and assignment format can catch them by surprise. Being used to knowledge assessment, writing essays to demonstrate their learning is unfamiliar to many international students. Choosing their own project topics and taking responsibility for their own learning contradicts with the culture of strong uncertainty avoidance that has strict rules and expectations. To help them tackle novel situations and undefined tasks:

- Explain learning objectives and assignments early to avoid potential frustrations from unmet expectations.

- Pay extra attention to clarifying ambiguous instructions such as “demonstrate understanding”, “show originality” etc.

- Proactively encourage students to ask clarifying questions and normalise this as OK to do. It saves students from guessing and academics from marking poor-quality work.

- Remind students they are responsible for their own learning and projects.

Mapping cultural differences to Bloom’s taxonomy learning objectives demonstrates the variance in instructional language. By targeting lower levels of the taxonomy of knowledge recall, less democratic countries seek to raise conformed individuals able to follow prescribed tasks and suppress the creativity and innovation that are valued in UK universities. Western higher education encourages students to master the art of scientific enquiry and self-manage their own learning, which are both very unstructured learning goals. Therefore, students’ and academics’ pedagogical expectations of instructional language differ.

Assessment feedback: ‘I did what you asked for, why don’t I get 100 per cent?’

In many Eastern countries, once a student delivers what’s expected, their marks are in the 90 to 100 per cent range. Therefore, it can be a shock to many when they get 60 to 70 per cent with a written commentary along the lines of, “Good job, you answered the question well”. Therefore, some students approach academics for an explanation of their marks. There are many who may not get in touch because of the power distance, but equally wonder why this is.

- Ask students how they feel about their mark and feedback. What do they think they did well and why?

- Explain that getting 60 to 70 is considered a success in the UK and that only a few students score above 80 or even 90.

- Check if they understand the feedback comments. Is there anything to clarify?

- How will they go about getting a better mark next time?

First, these differences in expectations are closely linked to the issue of uncertainty avoidance, which, ideally, should be addressed when providing the assignment brief and instructions. This is why explaining marking criteria in detail, with specific examples, is crucial.

Second, a feminine and masculine dimension to cultural differences applies. Feminine cultures value solidarity and social adaptation. Lower academic performance is not a big deal; an average student is the norm. Masculine societies seek brilliance, and academic failure can destroy students’ self-image, potentially leading to suicide in extreme cases. Masculine cultures prize competitiveness and the best students are considered the norm. Interestingly, the UK, China and India lean toward the masculine dimension, with students from these countries seeking feedback clarification with the view to perform better. Therefore students across the board tend to be motivated to achieve high; however, international students are used to getting much higher marks when performing well. Explaining the marking standards in the UK will help students understand their performance in context.

Disclaimer: The author wishes to acknowledge individual differences that exist within cultures. Although cultural differences are central to the piece, they do not reflect the unique characteristic of every individual. Thus the above may not apply to everyone in every situation.

Lenka Janik Blaskova is a lecturer in the psychology of education at the University of Exeter.

If you found this interesting and want advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.