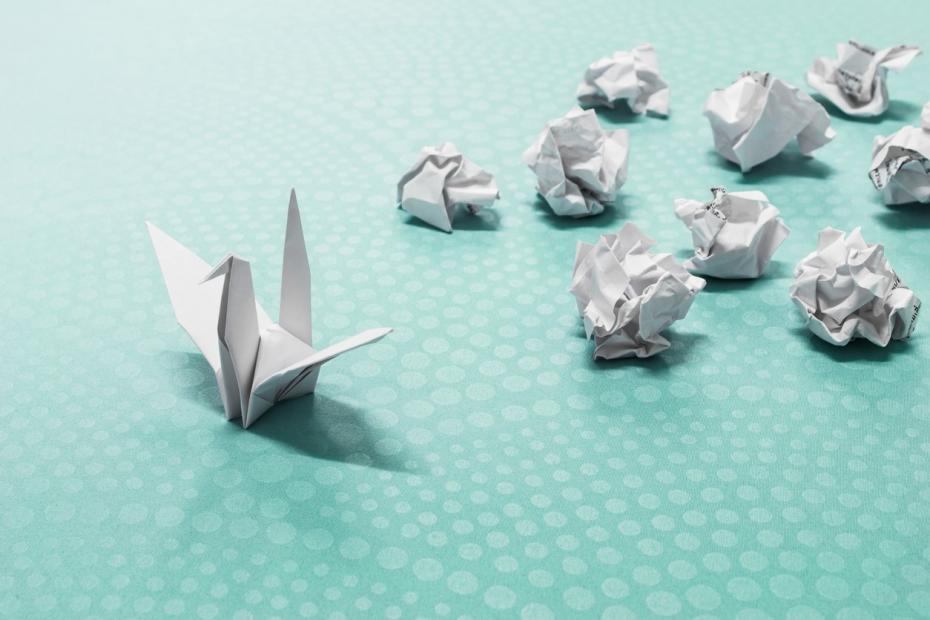

One write way to student success in mathematics

You may also like

Failing a course twice can put students in a difficult situation. Typically, the course is required and a third attempt requires special approval. However, this provides an opportunity to snatch success from the jaws of failure.

In our resource-limited urban public university, we’d like to provide all that better-resourced universities can afford. We cannot. But there’s opportunity to level the playing field.

In my role as department chair, I developed a structure for a two-strikes approach to turning course failure into a pass. Guiding students to articulate challenges and reformulate approaches, we build an improvement plan during a one-on-one meeting and a letter-writing task. The process, applicable beyond coursework, emphasises personal conversations, quality writing and reflective exercises that promote academic commitment and achievement.

Reframing failure as skill-building opportunity

The first step is a face-to-face conversation with the student. Verbal delivery is easy and succinct. Without using the word, I ask what brought past failure and what might bring future success. Is a teacher to blame? I sometimes point to Steven Zucker’s article “Telling the truth”: most college learning responsibility rests with the student; most learning takes place outside the classroom. This is general, inspiring reading, not an easy fix. Responses such as “I don’t need any more maths”, or “This course is holding me back from…”, or “I was always bad at maths” often lead me to bring up George Orwell’s 1984 and its Newspeak.

- Spotlight: How to fail well

- Decolonising learning through access to primary sources

- Why students are best placed to help students understand feedback

I suggest reframings, which might read: “No additional maths courses are required for my programme, though taking such may strengthen my background”, “Completing this class rounds out my programme. It’s required for my degree, with good reason” and “I may even become good at maths; think of maths as a new strength”.

I don’t post general suggestions online (on, say, web pages on course repeat policy), avoiding being prescriptive. I vary meeting themes. The writing guidelines are met without resistance, often with a smile.

Writing a path to success

The homework assignment comes next. Students write a request letter, outlining a path to success. I provide instructions, encourage hand note-taking and discourage electronics. “These are instructions, not dictation.” It should be made clear that quality writing is expected – English-paper grade, yet using the student’s own words. Plain-text format is required – no attachments, no graphics, colours or fonts. This emphasises word choice and gains logistic advantages:

I could express my thoughts…with a limited set of words and grammatical structures, as long as I combined them effectively and linked them together in a skilful manner. Haruki Murakami

The formatting requirement is always initially accepted, although submission in non-compliant form often follows. Attention to detail is important for all classes. Deviation from instructions is acceptable, but only with clear rationale. Alternatives are negotiable.

Writing guidelines follow. For clarity, a formal sentence is expected: “I request…support for...” This contradicts in your own words; no one objects. Next, when and with whom did you take the class? Everyone remembers when; many forget whom. “Look it up.” Detailed recall helps later.

Failure analysis comes next. Were first-strike lessons insufficient for second-attempt success? The student should list reforms, initiatives or new ideas for success. I offer suggestions, leveraging campus resources: tutoring, office hours, study groups… Some students with disabilities acknowledge special resources yet untapped; others learn of these for the first time. I encourage students to add ideas; friends and family are mentioned. Students’ ideas emanating from new directions (job, relatives, commuting) signal a successful conversation.

Specific study days/hours are reserved for this class and detailed in the letter. Not “two hours on Tuesday”; instead “Tuesdays, 2:30-4:30” reinforces the need to devote more outside than in-class time. (A 2:1 ratio is standard.) Students acknowledge that study-time allocations might have been meagre in the past. Length of time is not the only factor – time must be well spent (and instructor guidance is particularly valuable for that). Uncertain work schedules are mentioned. Then I suggest making a best guess, committing to later compensations, with no net loss. This section of the request letter is often weak. Careful re-reading of instructions and attention to detail yield improved revisions and will help future coursework. (Some write more than requested, including, for example, dog-walking schedules.)

Writing skill shortcomings emerge. Usage weaknesses appear among non-natives (“grab some lunch”) and natives (“reason being as”). I point out that good mathematics and good writing go hand in hand, linking to the writing centre.

Other considerations in the process

- What if a study schedule is made up? This rarely happens, I believe. Questions and remarks suggest sincere intentions. Why is whole-plan specificity important? Making choices is psychologically taxing. Weekly study-time decisions can be consuming.

- Weakness of fixed schedules? Benedict Carey’s How We Learn says that varying study venues helps. Why not vary time? Timing will vary, best intentions notwithstanding. Not to worry – there’s value in planning itself.

- Dividends are the good things emanating from course success. Sometimes a brief discussion of dividend is needed. The (ironic) post-Soviet peace dividend is recalled. Students go beyond grades and requirements in articulating success dividends – learning readiness or not needing to outsource mathematics in the workplace, for example. Envisioning dividends increases course value buy-in, driving success. Alongside positive dividends are negatives. Imagine a third strike. Envisioning negatives has greater impact than positives. Asymmetry can be leveraged.

- Priorities and responsibilities: During repeat, what’s the commitment load? Where does this course fit in? Excess specificity is common here. Don’t say “Taking my cousin to dialysis”; say “Family responsibilities.” Course priority need not be tops, but it should be high. Totality of responsibilities is also important. Is it right sized? Can we realistically expect to meet all expectations? Have these aspects been considered?

- Obstacles: What might impede success? How to circumvent them? We digress on obstacle. I cite a student offered 80 work hours in one week – good money, but school suffers. A prior commitment of 25 work hours makes it easier to say “Thanks; opportunity appreciated but I made a commitment…” Otherwise, resistance is hard.

This process seems longwinded when it’s written down; verbal delivery can be rapid. Successful requests are often short. When strong portions are present, with no red flags (poor writing, instructor blaming, dismissing course value, not following instructions), review is rapid. Feedback yields adequate revision in most other cases.

Mindset and positive (and contrapositive) psychology influence the process. Instruction copies are not provided, placing emphasis on conversation. There’s no script; delivery varies, guided by real-time student reactions.

Outcome statistics are not available. Negative recountings never arrive, positives sometimes:

Dear Professor, You supported my third retake request. I was thrilled… I earned a [high grade]… The appeal letter I wrote…helped tremendously!

Eric L. Grinberg is a professor in the department of mathematics at the University of Massachusetts Boston.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.