The rise and rise of the lecture-tainer

I have been teaching at university an awfully long time – almost 25 years, in fact. Before that, I was a student for a long time, too, as I clocked up four degrees. So, it’s fair to say I know a bit about university teaching, and how it has changed, from both sides of the podium.

The biggest change I have seen? Back in the day, the expert behind the lectern was totally focused on imparting facts and knowledge, whereas nowadays the emphasis is on being as entertaining as possible.

The university teacher now recognises that they have to first and foremost engage the student, and only then can they teach. Imparting wisdom is no longer enough. And, with so many more demands on students’ attention, we must work harder and harder to engage them.

- Build your teaching presence to better engage students

- Say goodbye to classroom boredom

- Resource collection: The post-pandemic university: how to serve the Covid generation

Welcome to the world of “lecture-taining”, where video clips, stories, interactive exercises, polls and quizzes have replaced the acetate overhead slides and monotone monologues about research of yesteryear – and content is secondary to being entertaining.

So, what has led to the change from lecturer to lecture-tainer? In a word, boredom.

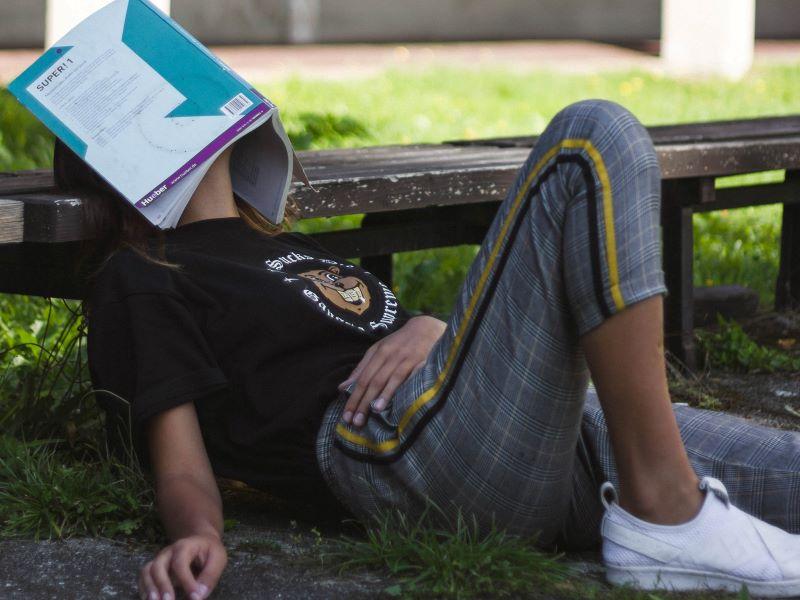

Boredom tolerance and experience have undergone a seismic shift over the past 25 years. Students these days seem to have a dramatically reduced attention span. One professor even claimed that today’s youngsters have an attention span of eight seconds. They get bored far more quickly.

I have been researching boredom for almost as long as I have been teaching at university. My own findings suggest that almost 60 per cent of students claim to be bored in at least half their lectures. A third claim that they are bored most of or all the time.

The reasons for this whopping dose of ennui at university are multiple. Society has shaped a generation with low boredom thresholds. Our world moves at breakneck speed; our lives are characterised by change and novelty – we can swipe or scroll to get the reward of new stimulation the second we grow even slightly bored.

It starts at school with the fast-paced, exciting interactive whiteboard culture. This is coupled with the Xboxes, iPads, Kindles and screens that provide ever-changing stimulation and feed our addiction to novelty. Our brains get a dopamine hit when we encounter something new. This provided an evolutionary advantage back in the day. The problem is that dopamine is addictive – the more we get, the more we need. This means we quickly bore of things and need our next fix of newness to keep our desire for stimulation satisfied.

Boredom in the post-pandemic era

And what effect has the pandemic had on boredom in the lecture theatre? Young people have become more accustomed to an online world where even their teaching has shifted online. This has fed their short attention spans as it allows them to stop and start (and restart) as their attention drifts and returns. For the watch-on-demand generation, the requirement to sit in a huge lecture theatre for two hours in real time is probably a big ask. If they struggled pre-Covid (and lecture attendance was not great then), they will certainly struggle now after two years’ reliance on dopamine-giving technology.

We really need to tone down the sensory overload we give children, so as to raise their boredom threshold. As a society we need to allow more boredom, not less, into our kids’ brains.

How to solve the boredom conundrum

So, what can we lecturers do? Must we learn to juggle or eat fire to keep students focused? I use the term lecture-tainer somewhat flippantly but we must acknowledge what we are up against. We can’t pretend that we can engage students with our mere presence any more; there are too many distractions coupled with a low boredom threshold.

We could block wi-fi and internet in lecture halls. I don’t think the answer is to bolt the stable door, though. We have to accept the situation and commit to entertaining and engaging – while balancing that with getting enough content in.

So, fire-eating is not necessary, but we do need to work with students, not against them. We need to make use of their need for novelty by adopting innovative teaching methods such as the flipped classroom or offering them Google-relevant material during a lecture. Teaching needs to be interactive to facilitate deep learning – and to check student engagement. Polls that use technology are popular, as they involve low cognitive load but foster high interest. Video clips ensure a constant change of pace akin to scrolling their newsfeed. Group work and audience participation keep students involved.

In my day, bored students could stare out of the window or pass notes to their friends (guilty!), daydream or doodle. Without phones and laptops, there was not much more to pull us away. We read books and used our imagination and creativity to fill in gaps in stimulation; we didn’t crave novelty as much because our brains weren’t as used to it.

I recently sat for a few hours at the back of a lecture theatre to see what students were doing behind their screens during lectures. I saw them chat to each other, text, do their supermarket shop and watch Netflix. Some did have the lecture slides open on their devices but often switched among other apps as their attention wandered. Like jealous lovers, these devices demand attention, seducing students back with constant notifications and pop-ups.

The lecture-tainer is clearly here to stay. We have to work with a shorter attention span, a lower threshold for boredom, and the immense smorgasbord of competing delights ready to tempt students away from us. Perhaps learning fire-eating skills is not such a bad idea after all.

Sandi Mann is senior lecturer in psychology at the University of Central Lancashire. She is the author of The Science of Boredom (Little Brown, 2016).

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered directly to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.