Teaching originality: an essential skill in the age of ChatGPT

Originality can be taught. With the dawn of the AI essay, this claim has big implications. AI synthesises very well, it compiles and compares in polished prose, but it cannot do innovation. Originality has turned from a desirable skill to an essential one. In How to be Original (published this summer by Sage) I offer another big claim: “anyone can be original”. There is no mystery to it. It is not the reserve of the beautiful few. It does take work, but with guidance and practice originality is something that students, at all levels, can practise and achieve.

Originality is an assessment criterion in most institutions, and it is invariably associated with the highest marks. But what it is and how it might be done are rarely explained to students. An aura of hushed and rarefied reverence gilds the topic: originality is not treated as a skill but a chalice. This sense of awe and wonder is sustained in the few attempts that have been made to tell students how it might be obtained. Students are pointed towards the practices and behaviours of famous geniuses.

- Not replacing but enhancing: using ChatGPT for academic writing

- A translation exercise to improve students’ creative writing

- Questions to foster open and engaging research communication

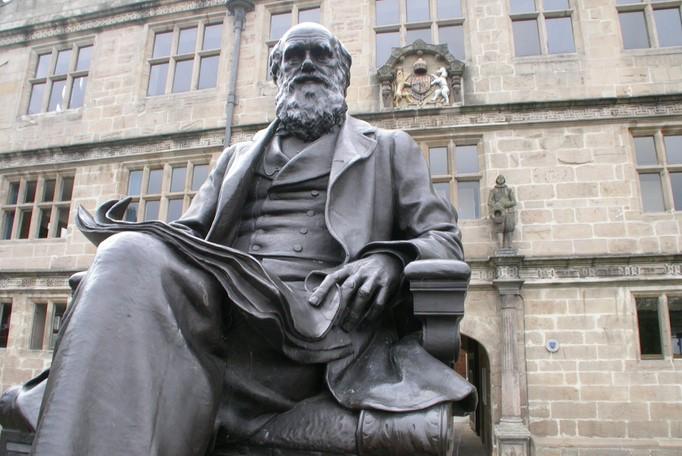

To paraphrase guidance provided by Marten Scheffer and others, we are instructed to learn from the habits of Charles Darwin, who each day took a walk upon his specially built “thinking path” in order to wrestle with knotty evolutionary problems. Hence, students are directed to take a walk every day, to put away their smartphones and seek out quiet spaces. Another recommended habit is meeting diverse groups of people; encounters that might provoke new ideas.

These tips might serve a purpose in making students realise that originality requires contemplation and connection. But they err in two ways. First, in making paradigm shifters such as Darwin role models. Second, by implying that originality comes from happenstance or simply from the ether, falling on ramblers like enchanted dust.

Academic originality is not about chance, genius or magic. It is about engagement and a clear sense of scholarly contribution. Its aim is not a revolution in thought but something modest and do-able, namely adding value to the literature. Such a contribution requires work. It is not as easy as falling out of bed, but it is within reach. You don’t need to build a “thinking path” to be original.

Originality is about knowing what has gone before and, in some specific and useful way, adding to it. One simple example is geographical: you take a topic but transpose it somewhere different, somewhere relatively new. Say a student needs to write an essay on environmental education. Why stick to the UK or US? Looking at environmental education in Madagascar might shed new light on the topic and make their essay stand out.

Another example involves engaging and developing an academic phrase or label. Take, for example, the sociologist Richard Florida’s concept of the “creative class”. This social categorisation identifies “creatives” as being key to the success of contemporary cities. We can work with this label by expanding it, making it longer and more specific: “racialised creative class” or “diasporic creative class”, for example. Nothing arcane or highly complex is going on here, but a contribution, an imaginative adding-on, is being made.

Taking inspiration from another discipline or sub-discipline is another common and relatively reliable way of “adding value” to a topic. Sentences such as “this essay draws on the emerging sub-field of island studies” or “in this presentation I will be developing some insights from environmental psychology” indicate that this work is going beyond the usual and hints at why (because it is “emerging”, because of “insights”). Notice that these sentences point to specific fields. This is more useful than, for example, claiming to be drawing on “insights from philosophy”. Philosophy is extremely diverse, so “insights from philosophy” sounds vague and ill-informed.

I need to add a word of warning about the “gap argument”. A gap argument states that something needs to be done because it hasn’t been done. This would lead us to claim that, for example, there is little or no work on arts policy in Morocco, therefore there needs to be some. This sounds reasonable, but it is not compelling. The problem is that gap arguments postpone the “why?” question rather than answering it. Why fill this gap? It is not self-evident.

The gap argument is not necessarily wrong – it can be part of an explanation – but it is never sufficient. Originality has to be justified and anchored in the literature. In this instance we might do so by referencing the fact that scholars have called for the internationalisation of the study of arts policy or by arguing that the Moroccan government has instituted a distinct approach to arts policy funding. Explanation and justification are essential for originality to appear substantive and succeed.

These examples derive from the social sciences and humanities. Science education has a different relationship to originality as well as to essay writing. But the basic principle is the same: innovation emerges from knowledge and engagement.

In many ways AI and its offshoots, such as ChatGPT, are to be welcomed. If it stimulates a turn towards innovation then the advent of the “AI essay” will enliven and enhance student learning. Rather than assessing students on how well they summarise and regurgitate, this new pedagogic environment will require more challenging and exciting tasks.

Although a few students might read How to be Original and hit the ground running, in most cases achieving originality is going to need individual academic guidance. Flourishing, student-centred universities in the age of AI will require more small-group, collaborative work, but also one-to-one tuition and supervision. This sounds paradoxical, but it is inevitable. We will be asking students to engage, to innovate. This means talking through ideas with students, discarding bad ones, arriving at better ones. Encouraging originality cannot just be a claim, a statement of intent; it needs resources, and the most important of these resources is staff who have the skills and time to work with students. Those institutions that already provide a high level of academic student support may well come out the winners in the AI revolution.

Some will say that this is all for naught, for soon AI will learn how to be original. The examples I have given – geographical relocation and rejigging academic labels – are straightforward, learnable and, hence, could be incorporated into future versions of AI. This is not far-fetched, but it’s still a long way off. Moreover, without the capacity of understanding – which arises from sentience – AI’s innovation skills might, just might, be inherently limited.

Alastair Bonnett is a professor of social geography at Newcastle University, UK.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the THE Campus newsletter.