‘You’re my only hope’: embedding holographic learning experiences into teaching

You may also like

Much has been said on the topic of virtual reality (VR) as a means for enhancing learning outcomes for university students. How can it enable teaching activities that would otherwise be dangerous, impossible, counter-productive or expensive in real-world settings (the so-called DICE criteria for VR in education and training)?

Despite the promise, two central problems for VR exist. First, the difficulty of on-boarding: it takes time to become familiar, confident and proficient with the technology. Second, sickness: despite significant improvements in the technology, it is inevitable that a minority of students (and teachers) will be unable to use immersive headsets, as they can cause dizziness, nausea or eye strain in certain people.

- Three approaches to improve your online teaching

- Harness human and artificial intelligence to improve classroom debates

- Using VR to change medical students’ attitudes towards older patients

Technology that aims to provide a holographic experience offers a solution here, providing several of the benefits of immersion. One of these is co-presence: the illusion of being there with someone who isn’t actually physically present. The technology also has low barriers, meaning that diverse and inclusive university communities can access the content provided.

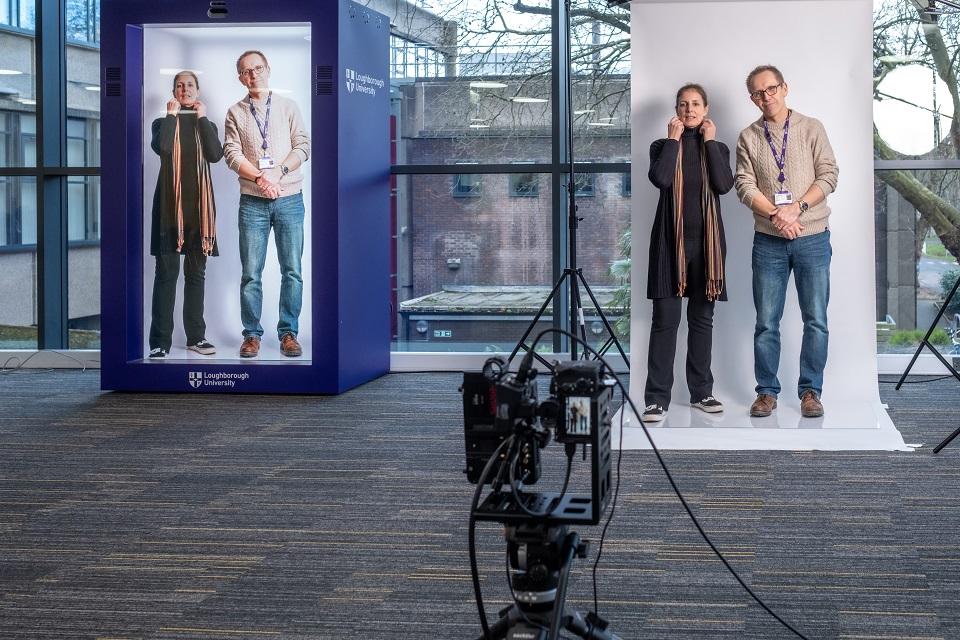

At Loughborough University, we are just starting to use holographic experiences in student-facing teaching. There are a range of possible immersive technologies in existence – and we are currently exploring use of “box-type” displays (human and table-top sized) that use high-quality transparent LEDs and various lighting effects to give a realistic impression of a 3D person or object. For the next six to 12 months the goals are to conduct the practice-informed research to understand the fundamental affordances of this technology, and its subsequent impact on the student learning experience. We want to develop the policy and training materials to empower academics to use this technology effectively.

We see several ways it could be used, although this number will no doubt increase with our experience.

Remote teaching: It is common practice to have guest lecturers and industry speakers contributing to university modules, allowing students to benefit from expertise not readily available within the institution while gaining broader, more global perspectives on problems. Such guests either need to be shown in 2D on a screen or must travel, costing time, money and CO2. In our planned investigations with the technology, we’ll aim to understand whether a hologram guest is perceived by students to be socially present, as engaging as an in-the-room teacher and yet not distracting, which is always a possibility with novel technology.

Live innovation teaching: A potentially significant benefit of this technology will be control over the pixels, leading to a wide range of possible innovations in pedagogic practice. For example, different realistic scenarios could be presented to students with recorded content of actors and multiple decision points in the narrative that require focused debate in class. Students could also be shown modified versions of themselves, changed in size, age, gender or race, potentially in relation to a designed-artefact, as a means of stimulating in-depth discussion – for instance, concerning the impact of individual anthropometry (body size or shape) on issues of fit (reach, vision, clearance).

Student-generated content: Similarly, we envisage students in creative disciplines using this technology to imagine the impossible – potentially using principles of magical theatre to showcase themselves and their digital content in new, exciting, engaging and memorable ways. We anticipate the technology providing an additional and welcome dimension to our popular degree show events.

AI avatar interaction: The hologram doesn’t necessarily have to represent a living human and could be someone significant from the past – or even non-human. When combined with suitably tailored AI, students or the teacher can directly engage and ask questions to a realistic full-sized avatar and then analyse the answers in the context of the learning outcomes of the teaching session. We will be interested to explore how such an avatar could represent the values of the university to enhance the sense of community or portray a figure relevant to the teaching, to augment learning through contextualisation.

Holograms afford many innovations in higher education teaching practice. Students and their teachers increasingly will need new digital literacy skills for understanding and working with these new immersive technologies. We look forward to experimenting in the use of holograms over the coming months – and reporting back with our findings to the higher education community.

Gary Burnett is professor of digital creativity and Vikki Locke is professor of teaching practice, both at Loughborough University.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.