Just over two years ago, leading lights of the Western far right gathered in Budapest for a conference. Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán was the star of the show, flanked by a key ally: a journalist and co-founder of his ruling party who had previously insulted Jewish and Roma people in terms redolent of Nazi propaganda. And also addressing the Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC) was Baron Wharton of Yarm, chair of England’s Office for Students (OfS).

Close watchers of UK higher education may well recall this episode. But it should have been a major scandal. Here was the man tasked by the government with overseeing English universities seemingly consorting happily with fascists and leading antisemitic conspiracy theorists. The (then) recent electoral victory of Orbán – a politician who forced the Central European University out of Hungary – was a “sign that we can win”, Wharton declared to the assembled comrades. When the University and College Union (UCU) called for Wharton’s removal from office in response, we were simply ignored by ministers.

The debacle of Wharton’s chairmanship serves as a grim case study in just how bad things got under Tory rule. Just what contempt did they hold us in to anoint such a figure chief custodian of the higher education sector? The OfS has itself come to embody the unending desecration of universities as a public good. Through this so-called regulator, the sector was subjected to both deepening marketisation and ideological meddling by hard-right culture warriors.

Bridget Phillipson’s arrival in the Department for Education has, therefore, been a breath of fresh air. Lord Wharton was gone within days, replaced by an interim chair, Sir David Behan, with a long, commendable record of public service in health and social care. Hugely welcome too are Labour’s decisions to refocus the OfS on the substantive issues facing the sector and to do away with the Tories’ ridiculous and deeply damaging free speech legislation.

“For too long, universities have been a political battlefield and treated with contempt, rather than as a public good, distracting people from the core issues they face,” Phillipson said in a statement to the House of Commons. We could not agree more. Having a government eager to engage and work in partnership with the union and the sector more widely is a basic precondition for starting to repair our universities.

A positive start, then. But we need action from Labour that goes beyond warm words and regulatory tinkering. And we need it fast, such is the depth of the rot. When it comes to the OfS, we in the UCU would like to see a much more thoroughgoing repurposing.

In recent years, the regulator has been the bearer of the government’s two-pronged posture towards English higher education: hands off economically and industrially, leaving the sector to be degraded by market rule and institutionalised mismanagement; and hands on politically – authoritarian ministers increasingly interfering with academic and campus life, imperilling the rights they claimed to be safeguarding. We could call it the Policy Exchange cocktail.

The new government’s approach needs to be the inverse: economically and industrially interventionist, but politically laissez-faire. That is the recipe for restoring our universities as a public good and stemming their global decline. Tasking the OfS with guaranteeing their financial sustainability while dispensing with the fake free-speech crusade is a step in the right direction.

But the regulator should be given a much more comprehensive remit: assessing and then repairing the damage done by marketisation. That could begin with a review of the malign bureaucratic procedures, gratuitous competitive exercises and Carillion-esque corporate governance practices introduced to universities by the market experiment.

In a way, the commodification of higher learning is baked into the conception of the OfS, announced by its very name. It aims to ensure “value for money” for students as consumers in a quasi-market. It should rather look to enrich their experiences as learners in a public higher education system. That task would in turn be inextricable from uplifting the pay and working conditions of UCU members.

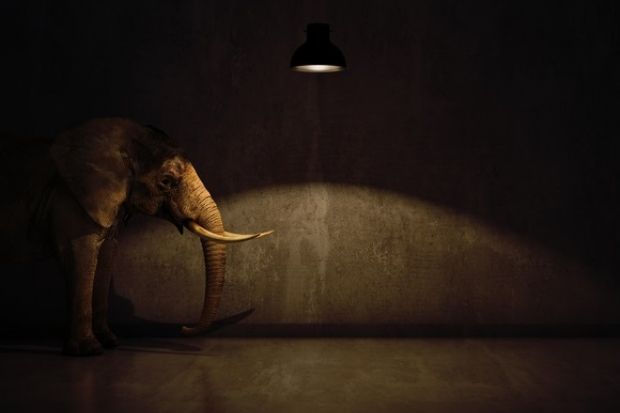

However, even a reformed, perhaps renamed OfS will make little difference if the Treasury stands in the way. The financial elephant in the room grows larger each day: neither the sector’s immediate financial crisis nor its deep-seated long-term problems can be addressed without new public investment. Public First’s recent proposal of a £2.5 billion emergency fund for universities at serious risk is really the bare minimum ask for a government that aims to stabilise the sector, never mind prudently manage it.

Even such an emergency fund would be a sticking plaster. With just a three-percentage-point increase in corporation tax, our report in May showed, tuition fees for domestic students could be scrapped. If we do not see massively increased public funding for higher education on a long-term basis then it – perhaps the UK’s last world-leading sector – will continue to wither on the vine. That would be, to say the least, an unfortunate outcome for a government that has tasked itself with national renewal.

It is genuinely heartening to have an education secretary who values universities as a public good and is determined to restore their standing. But the road will only be made by walking. Labour must go through, not around, the challenges of funding and deep reform. It should aim at returning universities to where they belong: the decommodified public realm.

Jo Grady is general secretary of the University and College Union.