As Narendra Modi begins his third term as India’s prime minister, universities and colleges will be wondering how his reduced majority and reliance on coalition partners will affect higher education policy.

Government policy has certainly affected Indian universities under Modi. The National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 recommends that they embrace interdisciplinarity in their teaching and develop flexible curricular structures that align with national priorities and global trends. It also emphasises flexibility in course selection and includes the Academic Bank of Credits (ABC) to facilitate seamless credit transfers.

However, it is the evolving aspirations of students and the shifting demands of a dynamic job market that have been fundamentally transforming Indian higher education in recent years. And a careful analysis reveals that elite public and private institutions often lead the way in adapting to student demands, frequently implementing changes ahead of official policy recommendations.

For many decades following independence, the majority of Indian higher education institutions focused primarily on knowledge dissemination, offering a wide range of programmes across the disciplines. Renowned institutions such as the University of Delhi, the University of Calcutta, the University of Madras, St Stephen’s College, Delhi and Madras Christian College were known for their bachelor’s and master’s programmes in the arts, humanities, social sciences and natural sciences.

However, while conventional programmes continue to form the foundation of Indian higher education, second-generation college students, raised in a more globally connected world, are finding traditional programmes offered by lesser-known institutions less attractive.

These students question the value proposition of traditional education, especially in fields where practical skills are more highly valued than theoretical knowledge. Their aspirations for quality education and international exposure make many traditional programmes less appealing to them, especially if the courses lack industry relevance. The more affluent among these students are increasingly willing and able to cross state and international borders for education, while the less affluent are shopping around for the best professional returns on their investments.

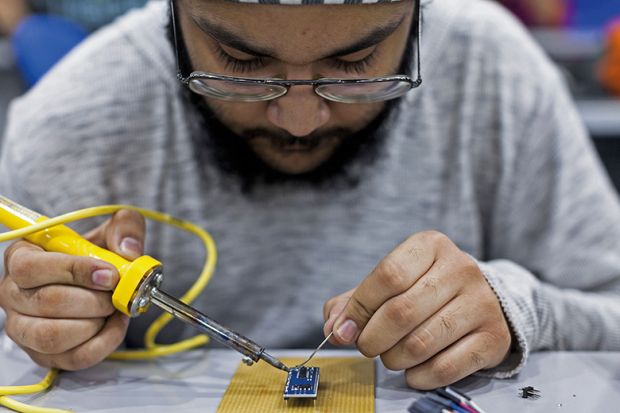

The shift towards prioritising practical skills is not a recent phenomenon, but it has intensified in recent years. This is evident in the growing popularity of programmes and courses related to data science, artificial intelligence, machine learning and other emerging technological fields in Indian institutions.

India’s higher education system is highly stratified, with prestige concentrated in the relatively small number of top institutions. But even some of these have begun developing entirely new programmes to better meet student needs and address job market demands. One example is the Indian Institute of Technology Madras, which recently established the Wadhwani School of Data Science & AI with a view to becoming a global hub for education and research in these burgeoning fields. Its programmes include a joint master’s with the University of Birmingham.

This strategic focus on high-demand fields is evident across many other Indian institutions. For instance, the Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru recently began offering an MTech in computational and data science; Symbiosis Institute of Technology has a BTech in robotics and automation. Chandigarh University offers a BSc in animation, VFX and gaming; and Shiv Nadar University has an MTech in artificial intelligence and data science.

A large number of Indian students are more inclined towards programmes that blend technology with management principles, such as business analytics and technology management, and those focusing on emerging sectors, such as fintech, health informatics and gaming. These preferences indicate a shift towards flexible and interdisciplinary skill sets, but many traditional institutions have been slow to adapt, resulting in the closure of more than 1,000 undergraduate, postgraduate and diploma programmes in engineering, computer science and management disciplines during 2020-21 alone.

This trend is exacerbated by the rise of online education platforms, coding boot camps and other alternative education providers, which offer more flexible and often cheaper learning options. Platforms such as Coursera, edX, Udemy, UpGrad, Udacity, Simplilearn, FutureLearn, Pluralsight and Duolingo allow students – as well as established professionals – to acquire interdisciplinary skill sets with micro-qualifications that are increasingly being recognised by industry. These platforms are now tailoring their content specifically to the Indian market, too. For instance, Coursera has started using AI technology to translate courses into Hindi and Tamil.

Many higher education institutions, especially in the private sector, are responding to these trends by offering more accessible and specialised programmes, such as those accredited by the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB) and the Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology (ABET). Meanwhile, even prestigious public institutions such as the IITs and the Indian Institutes of Management (IIMs) have developed a variety of online courses of their own. For instance, IIT Madras offers non-campus undergraduate programmes in data science and application, while IIM Bangalore provides online courses in management and business analytics through platforms such as edX.

The majority of Indian institutions do not have established systems for periodic curriculum reviews that engage various stakeholders to ensure diverse perspectives. But they must develop them. Students are often more aware of their educational needs than their teachers are; institutions must actively engage with them and incorporate their feedback into the development of new market-relevant programmes.

If they fail to do so, large numbers of traditional universities face an uncertain future.

Eldho Mathews is a programme officer (internationalisation of higher education) at the Kerala State Higher Education Council in India.