A few days ago, we were alerted to an email sent by a UK vice-chancellor to all staff over the summer. It started like this: “Put straightforwardly, our student experience scores reflected in the [National Student Survey] are terrible. Unacceptable. Yes, there are some exceptions. Yes, it is a flawed instrument. Yes, we educate a group of students with particular challenges and demands. These, however, are excuses and simply do not hold up.”

Not exactly inspiring reading ahead of a new term – especially for those keeping up with emails even when they are supposed to be on holiday. But perhaps this was just the preamble to a management mea culpa about unsustainable workloads and a lack of collegiate support? Not a bit of it. While the v-c recognises “the work that has been (and is being) put into addressing this situation, and the individual effort…something is still not working and part of that is the need for a sense of collective ownership and action”.

The bottom line is that “we cannot tolerate this any longer. It has to change, and change now. Radically. The next round of the NSS has to show massive improvement, and we need to keep improving.”

Just in case someone was still not getting it, the v-c goes on to suggest that while “it is easy to blame other people”, “it is your responsibility to make it change”, meaning “working for change across the system”. Unless this is done and “now”, “we will simply close programmes, […] whatever the consequences”, “we will place Departments into ‘special measures’”, and “when it comes to promotions, we will hold individuals to account for the student experience on the programmes they have a part in delivering”.

Setting aside the flawed nature of the NSS as a mechanism of measurement and control, which this v-c acknowledges in passing, the email is simply poor management through and through. It is bullying, dismissive and purposefully ignorant of the context in which staff work and in which the NSS operates.

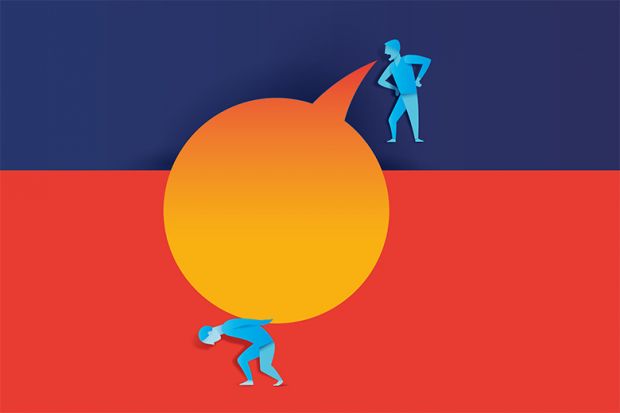

In our collective decades-long experience of UK universities, we have known perhaps a handful of colleagues who are openly dismissive of teaching. By contrast, we know many, many hundreds worked off their feet, balancing constantly increasing tasks, all with ever-decreasing levels of support. The implied staff indifference or sheer laziness is highly unlikely to be the explanation for “badly prepared teaching” and “ill-thought-out assessment”, not to mention “cursory feedback” and “not listening”.

Moreover, the idea that we are collectively responsible is only feasible if we collectively own the whole experience – which we don’t. Individual staff do not control scheduling of classes and rooms. Nor do they control the quality of tech support, or colleagues’ curricula or pedagogy, or whether those colleagues leave or get sick at the last minute.

As management professors, we know a little bit about leadership amid change. Put simply: if you want people to go beyond the call of duty – that is, use discretionary effort that is often not recognised in formal work allocation models – involve them purposefully. Communicate early and respectfully. Facilitate genuine ownership. Recognise good practice. Celebrate progress. Invest in support.

The belligerent tone of this v-c’s email will, at best, lead to surface-level compliance, with staff looking for any way out they can find. And no wonder – why would you give your best to an institution that does not give its best to you?

One of the reasons for the university’s poor student experience listed by the v-c was “lack of respect and kindness”. One wonders why staff, directed to provide it to others, are not afforded it themselves. We know that people reciprocate the attitudes and behaviours that senior managers show to them.

Of course, this email itself is only the ugly tip of the iceberg. It is another reminder of the misguided approach some university leaders have taken in their quest for continued improvement of their institutions. The damage the approaches have inflicted on the sector as a whole has been grave. A 2021 Education Support report found that 53 per cent of the 2,046 university staff it surveyed showed signs of probable depression, 62 per cent regularly worked more than 40 hours a week and 59 per cent hesitated to get support for fear of appearing “weak”. Bullying is rampant, as are declining wages, pensions and working conditions.

We also have plenty of evidence of the personal cost to individual staff of such management tactics. Stefan Grimm killed himself in 2014, after Imperial College London exerted undue pressure on him to secure more external funding. Malcolm Anderson took his own life after his managers at Cardiff University gave him 418 exam scripts to mark within a 20-day period – on top of other work.

While these are extreme examples, on the eve of yet another strike ballot, we know that colleagues across the sector are reporting acute levels of stress, made worse in too many cases by bad management. We know leaders can do better than this – we teach them how.

As the v-c put it, “none of this is rocket science”. Well, indeed.

The authors are two senior management academics who work in leading UK business schools and who wish to remain anonymous.