We social scientists have a hard time conceptualising the emotional dimensions of religion. Especially when describing its high-octane variants, we take refuge in external variables such as gender and race or report informants’ ready-made narratives of the highs and lows of conversion. But, for understandable reasons, we are deeply resistant to taking seriously what they tell us: we have been educated to take religious adherence as a symptom of something else – big-picture changes such as secularisation, strains in society or psychological problems. “They” must be lost, seeking for “meaning” and so on.

To those who find this kind of sociology boring and frustrating, Helena Hansen’s unique attempt to think behind the symptoms, in a book at once passionate and poised, comes as a welcome relief. If some are surprised that she sometimes follows everyday evangelical routines such as carrying a Bible or that she has even wondered “if God was asking me to go native”, that is a price worth paying.

Hansen expounds convincingly the encounter between two worlds of addiction and so helped me to understand that the innumerable recovery stories I have heard while doing research in Brazilian Pentecostal churches are not incidental: ministers rate their successes by the numbers who graduate to a life as church workers or preachers who addictively repeat their stories to any who might listen. Where once they dedicated their skills to the trickery and manipulation needed to access their drugs, now they dedicate them to managing congregations, to controlling people in recovery. After all, is not endless repetition a defining feature both of ritual and of addiction?

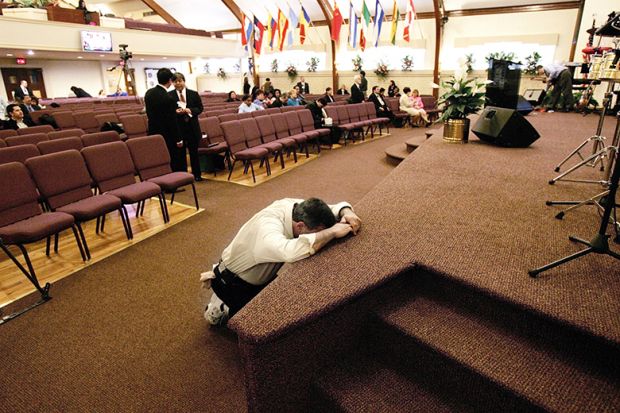

This hitherto largely unnoticed, but remarkable and highly original, book, based on Hansen’s extensive ethnographic work in Puerto Rico dating back to the late 1990s, and on her equally extensive experience as a psychiatrist, makes the case that the churches achieve some degree of success by adopting an approach that is the opposite of that of psychiatrists. From the perspective of standard biomedical psychiatry, addicts are “cases” who have lost the ability to take decisions about their lives: as humans, they are to be kept at a safe distance. For the churches, by contrast, they are people, and bodies, to be touched and handled and almost compelled to renounce their addiction even through the most terrible pain of withdrawal. For the ethnographer, this is not, or not exactly, “faith healing”, even if the retrospective narratives of Hansen’s informants, replete with hallucinations, visions, dreams and intimate conversations with God, do make it sound as if it is.

The book ends on a significant note of caution: if they are to recover in the long term, addicts need the support of an alternative family, which may be the church or the remains of their former network. Sending them “back to their families” is seriously misguided because such families are usually riddled with trouble of all kinds and may in any case have rejected them because of their addictions.

Hansen’s concluding chapter describes public treatment centres that bring addicts into daily community activities such as art therapy, farming and gardening in conjunction with “maintenance medications” such as methadone, which are “stop-gap measures to keep people from craving the drugs of their choice”. It sounds promising, but I suspect it is only for the select or lucky few.

David Lehmann is emeritus reader in social science at the University of Cambridge and the author of The Prism of Race: The Politics and Ideology of Affirmative Action in Brazil (2018).

Addicted to Christ: Remaking Men in Puerto Rican Pentecostal Drug Ministries

By Helena Hansen

University of California Press

232pp, £66.00 and £27.00

ISBN 9780520298033 and 9780520298040

Published 20 June 2018

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Clean at last, thank God almighty

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?