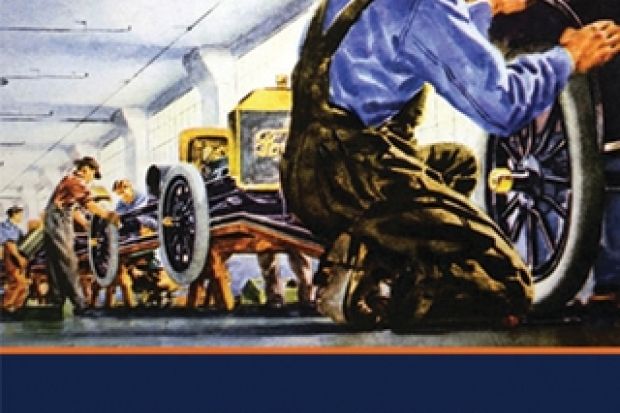

Claimed to have been invented a century ago, the assembly line has long since lost the lustre it once enjoyed. Henry Ford is commonly credited with this remarkable achievement in 1913, but fellow American Ransom Olds created the first automobile assembly line in 1901 and quadrupled his company’s output within a year. Where other pioneering US (and European) automobile makers focused on luxury cars for wealthy customers, Olds and Ford recognised the huge potential middle-class market for cheaper cars.

Olds was later surpassed by Ford, who recruited outstanding engineers, mechanics and designers. Five basic principles partly derived from other industries shaped Ford’s assembly lines: interchangeable parts, single- function machines, sequential ordering of machines, continuous flow of materials to workers via slides and belts, and precise division of labour. As Ford’s assembly lines grew larger and more complex, his workers’ individual tasks became simpler and more repetitive. The first Model T appeared in 1908. Ironically, it remained too costly for most Ford workers.

From then until 19, when the last Model T was produced, Ford made the assembly line the object of international fascination and praise. Other industries throughout the world would eventually adopt his manufacturing principles, although not all. The skilled workers of Swedish auto plants built around teamwork and multiple jobs are a notable partial exception. Also, European intellectuals such as Walter Benjamin lambasted Ford and “Fordism” without acknowledging the many obstacles to its implementation in countries such as the UK, Germany and Russia: dominant worker control, political party interference and weaker consumer markets.

In 19, the Ford Motor Company shut down to retool its assembly lines and build the Model A to compete with the newly dominant General Motors. GM’s own assembly line innovations meant that it could offer a range of vehicles, rather than just one, and significant yearly style changes. In addition, the assembly line’s aura was fading, with Charlie Chaplin’s 1936 movie classic Modern Times capturing its inhumanity - and insanity. True, computers and robots have transformed assembly lines in recent decades, but today the term is most readily associated with fast-food restaurants.

David Nye also discusses fiction, paintings, plays and photographs that celebrated or damned the assembly line, along with subtler examples such as post-1945 cookie-cutter suburban housing. He also analyses changes in labour relations that generated greater pay and benefits for assembly line workers in the US. And he considers the update to the assembly line represented by the “lean manufacturing” process that in the 1980s permitted Japan’s auto industry to threaten America’s world supremacy - and, thanks to the adoption of “lean manufacturing” by the Big Three auto manufacturers, the US industry’s recent recovery and challenge back to Japan.

The virtual absence from US history of any equivalent of the 18th-century Luddite movement that opposed and sometimes destroyed new textile machinery is also considered here. Even amid the closing of countless auto and other assembly lines during the Great Depression, no such incidents occurred in the US. The assembly line itself was not blamed for the unprecedented economic catastrophe.

Although he mentions the decentralisation of production that assembly lines have allowed, Nye does not discuss Ford’s 19 Michigan village industries that I and other scholars have written about as the epitome of decentralised auto production. Several of those rural plants included small-scale assembly lines.

The US assembly line’s century of mixed blessings is nowhere more evident than in the rise, decline and partial revival of Detroit, once America’s fifth-largest city but now only its 18th. Its relics include many abandoned factories that once housed assembly lines. Yet other parts of the city are thriving, and “reinventing” assembly lines as they do. Nye’s fascinating book deserves a wide readership.