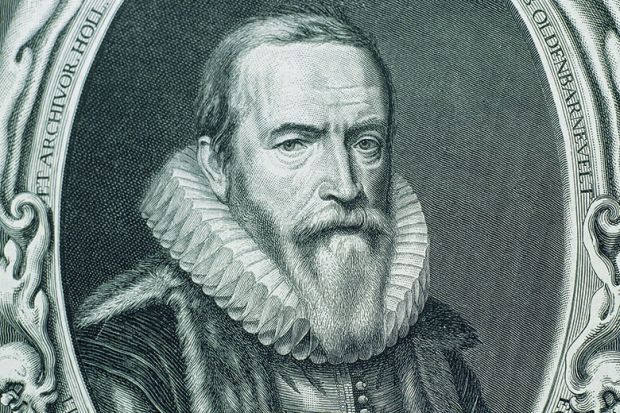

In 1619, faced by a kangaroo court of his enemies, the elderly Dutch statesman Johan van Oldenbarnevelt was sentenced to death on charges of treason. As the 71-year-old walked shakily up to the executioner’s block, watching in the packed crowd was a newspaperman, one Broer Jansz. Oldenbarnevelt was beheaded, and Jansz raced back to his printing house in Amsterdam, where within a day or so he produced a single-sheet eyewitness account. His gripping report spread the news of this seminal moment around the new Dutch Republic, and ended with a promise that “what follows next, I will communicate to you this coming Friday”.

Jansz is one of a fascinating cast that populates this tremendously ambitious history of the book trade in the Dutch world of the 17th century. The sense of alacrity, mobility and innovation in his story (Jansz’s newspaper was among the first in Amsterdam, and was still running thirty years later) runs through the entire work. Andrew Pettegree and Arthur der Weduwen’s narrative reveals the dynamism of the printing industry as it both documented and influenced the Dutch Republic. The authors take in a tremendous amount of printed material, yet despite its impressive scope their book has a wonderful sense of the granular materiality of its topic. We learn of wedding poems, printed on silk and handed out at ceremonies; university theses mouldering unread in Leiden and Utrecht; and the pile of books Hugo Grotius left on the floor of Loevestein Castle, unloaded from his chest in order to make room for the scholar to be smuggled away from his imprisonment.

This remarkable account is filled with such vignettes, that beautifully animate a subject that might otherwise be intimidatingly broad in scope. By the early 1600s, the Dutch Republic had the most concentrated group of printers, bookbinders and publishers anywhere in Europe, giving Pettegree and der Weduwen plenty of material to choose from. We meet the truculent young stationer Louis Elzevier, dodging baskets of spectacles sold at the Frankfurt book fair before founding what would become one of the most famous publishing houses in Europe. We encounter truly groundbreaking books, such as the Atlas Maior of the Amsterdam publisher Joan Blaeu, published in the 1660s in twelve volumes. At a price of around 450 gulden (and weighing in at over 70 kilos for a complete set), this was the most expensive book sold in the Dutch Republic. Immediately after its ten-year printing was completed, Blaeu’s workshop burned to the ground, including most of the edition’s 600 copperplate engravings and many unsold copies.

Despite its title, this work is interested not just in books but in the entire business of print. Pettegree and der Weduwen have made magnificent use of digital resources to offer a nimble history of the emergence of perhaps the most important centre of print in Europe. “When all the evidence is weighed,” the authors argue, “Dutch men and women purchased more books per head, and a wider variety of titles, than in any other part of Europe”. This basic sense of voracious literacy drives a compelling and impressive work.

Ben Higgins is a departmental lecturer in English at the University of Oxford.

The Bookshop of the World: Making and Trading Books in the Dutch Golden Age

By Andrew Pettegree and Arthur der Weduwen

Yale University Press, 496pp, £25.00

ISBN 9780300230079

Published 26 February 2019