Decades ago – generations, really – I used to teach political philosophy, including the history of the subject. Curiously, as it seems now, I managed to do this in two universities before my 23rd birthday and before the 1960s were over. It was invariably a compulsory course and not a popular one, since the majority of students seemed to find it threatening as well as extremely puzzling.

What I taught was considered “modern” philosophy and always started with Thomas Hobbes. Previous thinkers were either not modern or, like Machiavelli, were not philosophers despite being modern (although Machiavelli was “modern” enough to be regarded as wicked, in his own day, for taking no account of religion). When it came to making political theory feel relevant and up to date, the best texts were the Philosophy, Politics and Society collections, edited by Peter Laslett and W. G. Runciman. And here I sit, a considerable time having passed, reviewing a book on the history of ideas by David Runciman, son of W. G.; it is impossible for me not to think of him as Runciman the Younger.

The book arises out of his podcast Talking Politics, which has existed since 2016 but has thrived in the Covid period. And still we start with that dear old deeply frightened but long-lived bachelor, Hobbes.

In those earlier times there was a central question. It was, roughly, “On what principles can we justify the power of the modern state, whose protection we need, while limiting its power over us?” It led to a definite progression: from Hobbes to John Locke to Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Jeremy Bentham, Karl Marx and John Stuart Mill. (David Hume, though brilliant, didn't appear because he thought the question was a silly one.) As the progression continued, the central question was taken less seriously, since Marx and Engels saw the state as a kind of confidence trick designed to conceal exploitation, while Bentham believed the best form for it, whether democracy or “enlightened despotism”, could only be discovered empirically. The most elegant downgrading of the question was offered by Alexander Pope in his 1730s poem An Essay on Man: “For forms of government let fools contest/What’ere is best administer’d is best” – a slick sentiment which naturally infuriated several of the designers of the US constitution.

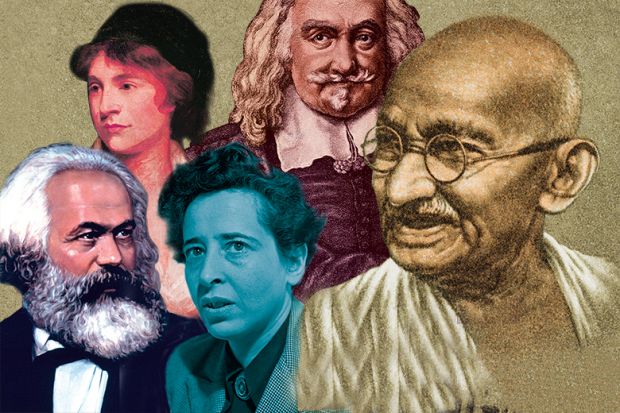

Runciman the Younger may start in the old place (and refer back to Hobbes a great deal), but his journey is very different and, as we now expect, is not confined to white males, but includes Mary Wollstonecraft, Hannah Arendt and Catharine MacKinnon and also men with at least some cultural heritage from outside Europe and North America: Mohandas Gandhi, Frantz Fanon and Francis Fukuyama. Apart from Hobbes, only Marx-with-Engels remains here from the original canon.

This is a studiously accessible work in two senses: it is written very simply and it constantly relates the ideas in the texts to issues being discussed today, something we rarely did back in the day. Thus Alexis de Tocqueville’s hopes and fears for the US the best part of two centuries ago are easily related to the phenomena presented by President Trump and the current fear of “populism”. It requires no great effort to see Wollstonecraft’s concerns about gender and power as foreshadowing current debates. And most of the writers described here can be read as having implications for debates about pandemics and climate change.

It is all very different from the study of political theory as we practised it all those years ago, asking students to answer questions on, for example, how many distinct senses of the word “law” were to be found in Hobbes’ Leviathan and how they related to each other. Part of what we thought the study was about was the development of mental gymnastics, a kind of scholasticism which didn’t care what the argument was about, but was merely concerned to understand its structure and test its structural weaknesses. (One of the nicer things that ever happened to me as a teacher was when a former student marched into my office, his face lit with triumph, and announced, “It’s amazing how useful political theory is when you have to appear at a public inquiry!”)

This book, on the other hand, assumes that it is the content itself that matters and that complexity is to be avoided in the interests of disseminating that content. It raises an interesting question about what can be achieved by a simple and accessible approach to complex matters. Popular science can still be good science, surely? And in politics, although we would not want a student to confine their studies of British government to the 1980s BBC television series Yes Minister and its sequel, Yes, Prime Minister, we might well want them to watch those programmes because, although they are a caricature of the politics they portray, they are a clever and insightful caricature.

At times the style of this book verges on a kind of tabloidy banality. For example, in discussing de Tocqueville and comparing his writing on France and America, Runciman remarks that “France was constrained in how it could experiment with democracy by two things that America lacked. France had history. It had centuries and centuries of history…” This reminded me of how, in those long-gone days when I taught political theory, I was living with a trainee journalist who regarded almost every sentence I ever wrote as absurdly long. (The other factor, incidentally, in constraining French possibilities is said to be the proximity of armed neighbours.)

For all that the style grated slightly, I don’t think there is anything wrong with the argument and I would recommend the essay on de Tocqueville and democracy as something that can be read at any level. But I think the value of these essays is uneven and I was much less satisfied with the one on Benjamin Constant and liberty. Runciman moves from a consideration of Constant’s comparison of “ancient” and “modern” conceptions of liberty to Isaiah Berlin’s distinction between “negative” and “positive” freedom and in doing so crosses the boundary between simplicity and superficiality. This is partly because, like most fairly orthodox thinkers in contemporary societies, he wants to import a good deal more equality into his version of liberty than is intrinsically or historically justified. I also think that “liberty” is inherently a more complex and ambiguous concept than “democracy”.

It is always worth asking what the purpose and audience for a book are supposed to be. This one doesn’t offer the skill of examining texts and arguments of the kind that my public inquiry friend was grateful for. The “general market” for writing with a philosophical content is notoriously elusive, although Runciman may have found his own route to that Eldorado through the podcast. What I would definitely recommend it for is the purpose for which Bertrand Russell’s Problems of Philosophy has often been used: it should be given to anyone thinking about studying political theory, political philosophy or forms of history that emphasise the history of ideas. If you are not absorbed by the ideas and connections – and ideas about connections – to be found here, then such study is not for you.

Lincoln Allison is emeritus reader in politics at the University of Warwick.

Confronting Leviathan: A History of Ideas

By David Runciman

Profile Books, 288pp, £20.00

ISBN 9781788167826

Published 9 September 2021

The author

David Runciman, professor of politics at the University of Cambridge, was born in north London and grew up in St John’s Wood, he recalls, “not far from the Beatles’ Abbey Road crossing. As a child, I remember a few tourists hanging around there – I’d have been pretty amazed to know that there would be many more now (even post-Covid), 50 years later.”

As an undergraduate at Cambridge, Runciman studied philosophy and then history, and so found himself “at the heart of exciting developments in the history of political thought, centred around the work of Quentin Skinner and John Dunn. I was always interested in how those methodological arguments concerning ideas in context related to contemporary politics…

“As electoral politics got more unpredictable over the past decade, I sensed a move away from blithe confidence in political science models and more interest in long-view history. Some of this is focused on the deep history of present injustices; some of it on the early origins of institutions we take for granted, including the state.” Podcasting has been a good way of exploring such themes because “it seems to suit serious conversations about history and politics”.

Asked why it is still useful to go back to Hobbes (or even Plato) when many of the key challenges we face are not only desperately urgent but literally unimaginable to them, Runciman responds that “the history of ideas can help with two things: to make us see what’s familiar about what we think is new, and what’s new about what we think is familiar. We need to go some way back to get that perspective, and the more disorienting in many ways, the better. Reading people whose concerns we recognise but who would find our world unimaginable can be a good way to spark our imaginations.”

Matthew Reisz

后记

Print headline: Thinking, then and now