These days, historians of China and foreign correspondents usually focus on a particular period or a single figure. What a pleasure to read a significant, original book that covers millennia of Chinese history in an informal, often chatty, but always learned style. That is the accomplishment of the University of British Columbia’s Timothy Brook, who shows how, since the non-Chinese Mongols conquered China in the 13th century, China’s rulers have seen themselves as a significant part of a much larger world, not a country but a Great State.

Brook contends that China has always been part of the larger world. While in the earliest era it was imagined that there were thousands of other countries, by the 3rd century BC the idea took root of a series of dynasties, each founded and ruled by Han family. Although these eras are usually divided into smaller sections with their own rulers, the idea (and ideal) of a dynastic China held sway and is still frequently employed today.

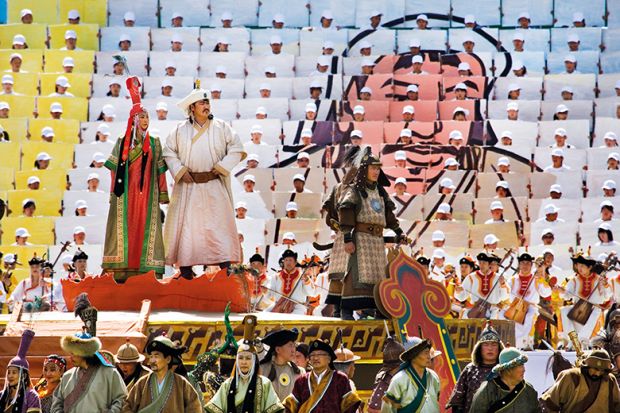

Then, in the 13th century, when centuries of Han dynastic family rule ended, the non-Han Mongols under the great Genghis Khan conquered China and the concept emerged of a Chinese Great State, ambitious – but failing – to conquer even Japan across the sea. This is a fruitful notion that Brook justifiably claims as his own (although he concedes that few Chinese today see their history in this way).

The concept of the Great State holds that the single family that had shattered the dynastic line now ruled over a far larger area, and incorporated its ideas and principles over vast distances. In chapter after chapter, Brook shows that this concept held through successive non-Han conquests until the establishment of the Republic in 1912.

In this Great State, Hans and non-Hans lived and interacted under a universal rule, an overarching ideal that Hans understood and respected, so that even Chinese pirates informed their victims that they were the prey of something not merely Chinese but far larger. The mighty Manchus, who dominated the dynasties ruling China from the 17th century to 1912, as Brook demonstrates, eventually needed support in suppressing the peoples under their heel. In 1719, the emperor’s son agreed the terms of the invasion of Tibet and required the blessing of the seventh Dalai Lama – something that Brook maintains (correctly, in my opinion) still bedevils relations between China and Tibet.

Even more fateful for the idea of the Great State in the late 19th century was the difference between how China and Japan reacted to the new imperialists from far away. Brook shows how the failing Manchus pushed back against the British, the French and, eventually, the Americans, while the Japanese sought to learn from and accommodate them, especially as they witnessed the Westerners’ impact on the once Great State. When the now-victorious Han republicans set about establishing their new Chinese state, they quickly discovered, according to Brook, that they had not created a new Great State. It is that huge weakness that the Chinese, from the time of Mao Zedong to that of Xi Jinping, have sought to remedy, from Central Asia and across the seas far from their shores – the policy that, as Brook skilfully makes clear, greatly alarms us today.

Jonathan Mirsky was formerly associate professor of Chinese history and comparative literature at Dartmouth College in the US.

Great State: China and the World

By Timothy Brook

Profile Books

464pp, £25.00

ISBN 9781781258286

Published 19 September 2019

后记

Print headline: All under heaven is a vast expanse

请先注册再继续

为何要注册?

- 注册是免费的,而且十分便捷

- 注册成功后,您每月可免费阅读3篇文章

- 订阅我们的邮件

已经注册或者是已订阅?