Two decades ago, my co-edited Explorations in Theology and Film received a scathing review. The essay collection, the reviewer remarked, was “as acutely embarrassing as those church services that try out rock music to fetch back the dwindling flock”. Twenty years on, I’d like to put Randall Stephens’ book into the hands of that reviewer. At the very least, it would highlight that, for all the tensions between religious faith and popular culture, the relationship is messier and much more interesting than is often supposed.

Christianity’s interweaving with the history of rock’n’roll might not always have been apparent. But that the two have indeed been locked together – in conflict as well as collusion – is the subject of this beautifully written, well-researched book. It helps to explain why Tom Jones could release the album Praise & Blame, although only in 2010, and now talks openly about having sung gospel songs and spirituals with Elvis in a way that would not have been possible in his early career.

Jones does not get a mention here, for Stephens is writing an American history, as a cultural historian. Yes, there are some references to the English scene. How could there not be, with the Fab Four “from the English port city of Liverpool” being so influential on both sides of the Atlantic, and with Cliff Richard linking up with Billy Graham? But what Stephens has provided is an extensively evidenced account of just how tetchy Christians – especially theologically and politically conservative Christians in the US – have been about popular music, while also wanting to make use of it when necessary to promote their version of the faith.

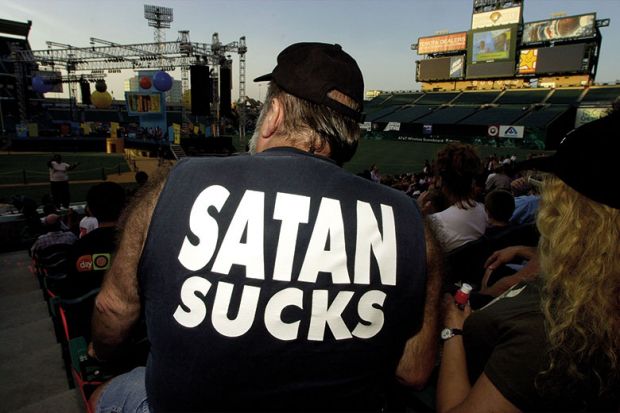

More interestingly, though, rock’n’roll emerged from a variety of Christian music in the first place. It has its roots in Pentecostalism: that form of Holy Spirit-filled Christianity that moved well beyond reason, stirred up emotions and encouraged all manner of not always creative wild behaviour. Pentecostalism enabled people to celebrate and enjoy the body’s movement, and encouraged them to sway and dance. Both Pentecostalism and rock’n’roll have proved uncomfortable for many Christians, so their combination was bound to cause problems. Rock’n’roll’s alliance with youthful rebellion, racial integration and drug culture created further difficulties, especially among white evangelicals.

Stephens logs all this impeccably, and locates the interplay between popular music and Christianity in the US within a broader framework of race relations, anti-communism, conservative politics and changing moral values. The advent of Jesus rock, while never fully accepted by music critics, signalled a marked change in the 1970s. It became more possible to like rock (even if not secular rock) and to be Christian, too.

Although Stephens does a great job within a limited frame of reference, there is much more to be asked. What about Christians who listened to secular rock? What about musicians who had no religious background and were hostile to religion? But that would require a much fuller account of rock’s history. In the meantime, there are two consequences: if Stephens is right, then Christians have been very foolish not to welcome rock’n’roll with open arms; and the God in whom Christians believe has been proving much more playfully creative than anyone has usually allowed.

Clive Marsh teaches at the University of Leicester and is co-author, with Vaughan S. Roberts, of Personal Jesus: How Popular Music Shapes Our Souls (2013). His book A Cultural Theology of Salvation will appear later this year.

The Devil’s Music: How Christians Inspired, Condemned, and Embraced Rock ’n’ Roll

By Randall J. Stephens

Harvard University Press

344pp, £21.95

ISBN 9780674980846

Publication 30 March 2018

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login