David Ripley, born in New Orleans in the 1830s, could never, even in the most private of his musings in his own bedroom, have imagined the ignominies a 21st-century historian would one day come to heap upon him. David, Jason Reid tells us, treasured one possession above all: a bust of the young Queen Victoria (persona non grata in most Southern US homes of the era), not least because it resembled one Emma Shields, a neighbour, and the object of what transpired to have been David’s less than wholesome desires. Victoria “may have been used as a masturbatory aid”, Reid writes, immediately conjuring up an altogether unexpected image for this reviewer, “acting as an antebellum equivalent of the Farrah Fawcett posters that popped up on the walls of numerous teen bedrooms during the 1970s and 1980s”.

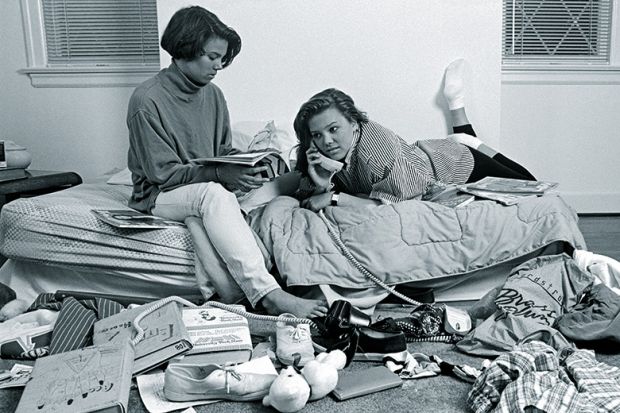

The site of the American teen bedroom, as Reid explores in this engaging and affectionately written book, has been freighted with a multitude of meanings over the past 200 years. Numerous experts have had their say, from psychoanalysts and interior designers to clergy, parenting specialists and sexologists. They have seen the space as cultural entity, extension of personality, or even as radically transformative phenomenon. In the early 1960s, for example, the psychoanalyst Peter Blos treated “Judy, a friendless teenage girl ‘disfigured’ by acne [whose] personality underwent several important changes when she was finally given a room of her own”.

Reid’s book is an examination of how and when the “autonomous teen bedroom” (his definition of “teen” is generous rather than mathematical) emerged, and what came to shape the cultural ideal whereby “the sleeping quarters of youth are expected to assume a prominent role in socializing teens and shaping their identities”. He maps a shift over those 200 years of American history, from the broadly Christian emphasis on constructing teens’ private spaces in the 18th and 19th centuries, to a far more secular, or scientific, conception in the 20th century and beyond. The change was also gendered: middle-class girls were likely, in the earliest examples, to have their own bedrooms long before their male counterparts did.

My favourite section of the book features Reid’s discussion of how the post-war market found in teenagers a new source of potential income, monetising the idea of the teenager’s bedroom, and producing goods designed specifically for it, from posters and accessories to furniture. I smiled in nostalgic recognition at Reid’s description of Seventeen magazine’s advice on how to “punk out” a teen bedroom. Regulated rebellion under the roof of the family home literally came at a price: “Youthful self-expression, as it turns out, was to be as safe and as prepackaged as any other consumer item sold during the waning years of the Cold War”.

Finally, review copies of books don’t arrive on a reviewer’s desk by magic. Many people work to get them there, and the books come with a slip of paper inside the front cover, put there by the publisher. This slip is usually utterly unremarkable, but the one tucked inside Reid’s book was delightful. “Dear reviewer”, it began, “What did your childhood bedroom look like? For me, it included a crafty ‘Ashley’s Room, you must knock’ sign and one of those very secure diaries with a tiny lock”. And, after Ashley’s signature on the slip, it reads, quite simply, “Please knock!”.

Emma Rees is professor of literature and gender studies, University of Chester, where she is director of the Institute of Gender Studies.

Get Out of My Room! A History of Teen Bedrooms in America

By Jason Reid

University of Chicago Press, 320pp, £31.50

ISBN 9780226409214

Published 13 February 2017

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: A chamber of secrets

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?