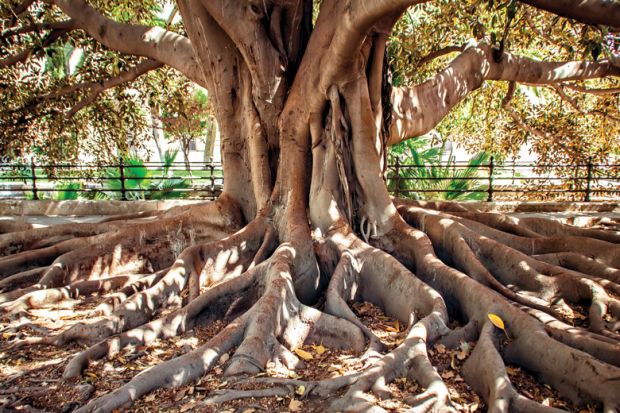

“Combining the stability of architecture, the fluidity of water, and the vitality of plant life, the root is a kind of supermetaphor that subsumes the others,” Christy Wampole writes. It is “snakelike, slithering in the depths”.

She recalls, but firmly sets aside, Lord Palmerston’s warning that “half the wrong conclusions at which mankind arrives are reached by the abuse of metaphors”, in order to commence her own headlong rush into such theorising. After all, metaphors and analogies are powerful precisely because of their flexibility and adaptability.

Yet she acknowledges just how slippery this particular metaphor is by noting that the habit of supposing that the root is older than the rest of the plant is actually misguided – the two grow and develop together. She notes too that the master of deconstruction, Jacques Derrida, explicitly condemns the root metaphor, saying that it is rather “a concealment of the origin”. Where Martin Heidegger and Edmund Husserl sought to “reroot” philosophy, Derrida sought to uproot it altogether, Wampole enthuses. Yet Derrida too was “very much a product of the phallogocentric system he critiques”. He fails to condemn roots as male images, conservative reactionary forces. Root-seeking is based on the idea that the past was better, that origins were purer.

Wampole arrives instead at rhizomes as the progressive, non-hierarchical, feminist, solution – although she allows that even after “ruminating long and hard” she is still not sure what a rhizome is. She is left with the worry that “the botanical metaphor I’ve followed throughout the book with assurance has dissolved in the hands of Deleuze and Guattari”, with their dramatic plea: “Make rhizomes, not roots, never plant! Don’t sow, grow offshoots! Don’t be one or multiple, be multiplicities!”

Ignoring that advice, Wampole continually narrows down the area of study in ways that seem arbitrary. She insists that it was in France and Germany “more than anywhere else” that cultural debates “organized themselves around the problems of roots and radicality”, and she then further concentrates on France owing to “the plain fact that I am a specialist in twentieth and twenty-first century French and Francophone literature”. As a result, Sartre’s dendrophobia – fear of trees – looms large here. Pity him! Because, for Wampole, “nearly every major philosophical breakthrough in twentieth-century Continental thought confronted the problem of rootedness explicitly”, becoming organised around “tropes of rootedness, groundedness, implantation, transplantation, and eradication”. She also says that the late 19th and early 20th centuries witnessed an obsessive search for origins, yet clearly the search has been pretty timeless.

Acknowledging that it would be impossible “and unavailing” to catalogue all the uses of the root metaphor in 21st-century poetry, she has a good go anyway, with four poets few will have heard of. In the process we are urged to deconstruct the double “X” in Paul Celan’s poem Radix, Matrix: “X marks the spot, that place in the ground where the person and race originated.” Another poem she considers uses lots of hyphens, which is revealing, she assures us, because this is also the symbol for “negation, lessening, lowering and extinction”. Yet another reminds Wampole that the word “root” also means “penis” – as in radix virilis. No wonder Derrida saw in all this an emblematic circumcision.

Martin Cohen is editor of The Philosopher and author, most recently, of Paradigm Shift: How Expert Opinions Keep Changing on Life, the Universe and Everything (2015).

Rootedness: The Ramifications of a Metaphor

By Christy Wampole

University of Chicago Press, 288pp, £31.50

ISBN 9780226317656

Published 6 May 2016