Some of our favourite pop culture stories follow the bad-guy-turned-good trope, from Severus Snape in the Harry Potter series to Game of Thrones’ Jamie Lannister. John Gluck’s memoir falls into this genre – think St Augustine’s Confessions or The Autobiography of Malcolm X – illuminating his transformation from an animal-loving boy to a “hard-nosed” animal researcher, and then later into an animal rights activist.

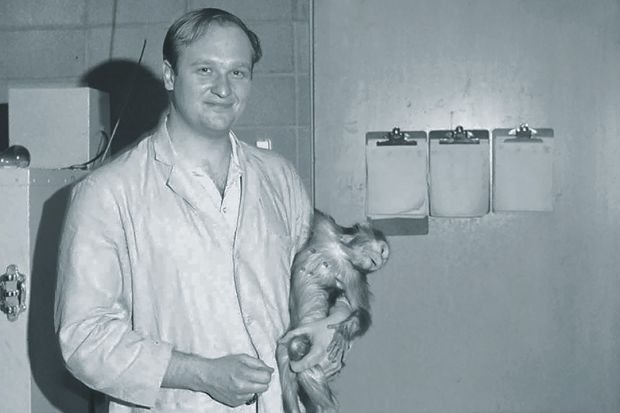

Whether Gluck was ever a bad boy is going to be a point of disagreement among readers, but that is how he portrays himself. Gluck was a student of the (in)famous animal psychologist Harry Harlow, known for experiments that involved separating infant rhesus macaques from their mothers soon after birth and raising them in social isolation. Monkeys raised in isolation for the first six to 12 months of life tended to share symptoms – the isolation syndrome – consisting of fearfulness and abnormal social and sexual behaviour. Harlow created this population to determine how to cure the monkeys, with the goal of helping humans suffering from psychological disorders.

Gluck came to Harlow’s Wisconsin Primate Laboratory as a PhD student in the late 1960s, after being trained as a behaviourist during his graduate studies at Texas Tech University. Readers get to see behind the curtain of this research programme, and Gluck’s descriptions are fascinating; I found it hard to turn away – half car crash, half Hello! There is a bit of a tell-all-story flavour to the descriptions of the characters involved in the Primate Lab during this era – monkeys and humans alike.

The transformation into a PhD student who could help kill “used” rats by throwing them at a brick wall, Gluck thinks, stems from a deliberate process of desensitisation to animal pain and mental life. Moving from New York to Texas, Gluck found that he could fit in by shooting rabbits and castrating bulls, proving he wasn’t just a soft city boy. His language changed, too. As behaviourists, Gluck’s first teachers demanded that students strip mental terms from their language, so that dogs who “barked and struggled to escape” instead emitted “vocalizations and extremely vigorous and topographically varied muscular actions”.

This depersonalising language was common at Wisconsin, too. Harlow was no behaviourist, but the animals were not named, only numbered, and pronouns used to refer to the animals were typically the impersonal pronoun “it”. This habit appears hard to break, as Gluck sometimes refers to animals as “it” and “which” in his book rather than using the personal pronouns “he” “she” and “who”. Uncritical acceptance of this way of speaking of animals – seeing them as objects rather than subjects – is a powerful impediment against seriously considering how we should treat these sentient beings.

And the language Gluck encountered had other powers. Rhetoric was colourful at the Primate Lab – the monkeys were “recruits into a just war against human suffering”, and graduate students were given exemptions when called to the Vietnam draft because of the national security implications of their work.

The second transformation, from an animal user to an animal rights activist, stems from the very same reasoning that motivated Gluck’s research. Monkeys have to be personified to an extent in order to serve as useful models of human mental illness. But they have to be different enough to justify causing them psychological harm and killing them in the pursuit of knowledge. This balancing act became hard for Gluck to maintain. “Hairy humans with tails” make good models of human psychology, because they share social, intellectual and emotional features with us, and these features are morally relevant. Looking back, Gluck finds it hard to believe that no one in the lab seemed to make the connection between monkey minds and monkey moral standing. But at the time, Gluck was surprised when one of his graduate students dedicated his thesis to the monkey who died in the course of the research. How could one dedicate a thesis to a thing?

Voracious Science and Vulnerable Animals is a brave book, because there is something in it that will anger those on different sides of the animal rights debate. I can predict that some advocates of the use of animals in research will claim that Gluck focuses too much on the harms and ignores the benefits, and that he creates more problems by letting outsiders peek behind the curtain. One might also worry that Gluck’s description of research practice is outdated, and that contemporary practices would never permit some of the housing situations and treatments prevalent in the 1960s and 1970s. Gluck’s claim about the immorality of social isolation experiments in particular challenges those who continue to engage in such research, such as his former graduate student colleague Stephen Suomi, whose research has recently been subject to intense Congressional scrutiny.

I can also predict that some critics of animal research will be appalled that despite Gluck’s ethical concerns, he gave his community of monkeys – individuals he didn’t know what to do with – to Suomi, who used them in further research. Many animal rights activists will likely also wish that Gluck went further in the book, by calling for an end to research rather than merely for better protections and consideration. Perhaps in part because Gluck’s actions do not fit into any neat ethical stereotype, the book is a compelling read, and he comes across as a real person engaged in an intense act of self-study, which he is willing to share with all, and despite the predictable backlashes.

While Gluck sees his journey as an ethical transformation, those looking for an explanation for this transformation will leave disappointed. There is nothing like Malcolm X’s hajj moment in Gluck’s story. Did he start to question his own research because he felt queasy about touring dog rooms full of broken and drugged animals, and then going home to his pet? Was it meeting and finding a way to communicate with Carolyn, a 16-year-old whose brain stem injury resulted in almost complete paralysis and an inability to speak? Was it one more student coming to his office handing him a copy of Peter Singer’s Animal Liberation? Or was it just that Gluck wasn’t able to transform the monkey research into theories or therapies that led to useful treatment for human depression or autism? There is little hint as to why Gluck’s life experiences set him on a different path from Suomi. What led to these two men’s different ethical choices? We can only wonder.

Any argument about the use of animals in research has to consider both the harms and the benefits involved. What Gluck gives us is a better understanding of the harms. He tells us that even with the best intentions, we sometimes inflict unnecessary pain; we sometimes start to cut open the skull of a monkey who isn’t fully anaesthetised. Even with the protections of the Animal Welfare Act, Gluck argues, the contemporary practice of working with animals fails to guarantee that we respect their interests. To have the frank and open ethical conversation that Gluck thinks we should have, we need to have the curtain fully drawn back, so we can see both the array of harms and the array of benefits. Reasoning fails in the dark.

Kristin Andrews is associate professor of philosophy and cognitive science, York University, Canada, and author of The Animal Mind: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Animal Cognition (2015).

Voracious Science and Vulnerable Animals: A Primate Scientist’s Ethical Journey

By John P. Gluck

University of Chicago Press, 360pp, £19.50

ISBN 9780226375656 and 5793

Published 28 November 2016

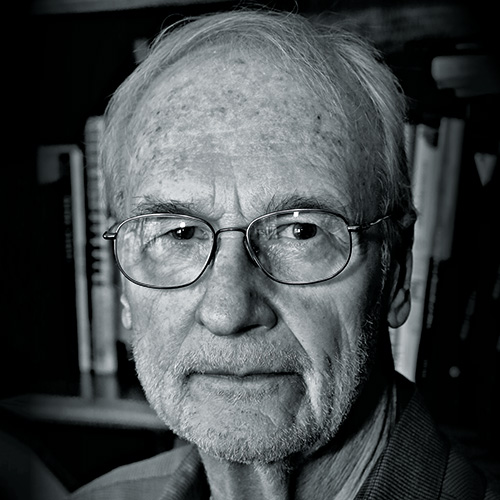

The author

John Gluck, emeritus professor of psychology at the University of New Mexico and affiliate faculty of the Kennedy Institute of Ethics, Georgetown University, was born in New York City, the son of a firefighter and a public school secretary.

“My parents, sister and I shared a comfortable but cramped basement apartment in a small row house. Early in my life, members of my immediate family came to suffer from a variety of serious medical disorders. I saw the false hope provided by useless medical interventions and the stoicism required to live despite the burden of disability,” he says.

Embarrassed at being labelled a “slow reader” in school, he “discovered that while I did read slowly, I could retain large amounts of information without additional effort. The ‘disability’ was actually an advantage.”

As a student at Texas Tech University, Gluck found a “completely alien” life: “effusively friendly people, real cowboys, big agriculture, large animals and guns. When I wasn’t in class or in the lab, I was working on friends’ farms and ranches. I saw food animals both respected for their strength and intelligence and treated like mechanical products. I was baffled by the clash of values.”

Does Gluck believe that this book will change his peers’ minds on the use of animals in research? “A cohort of long-time primate researchers have expressed opposition to my project and attacked my credibility, mostly by mentioning that I am old and out of touch and have even worked now and then with animal protection groups on matters upon which we had agreement. On the other hand, I have received thanks from some established scientists who appreciate the expression of ethical concern that I offer and express remorse about their lack of willingness to have done so more openly themselves. As Plato asserted, we don’t teach others ethics, we remind them.”

Karen Shook

后记

Print headline: How I started worrying and learned to love the monkeys