There is no doubt that laboratory experiments using live animals often get wildly out of hand. They probably always did, from the earliest days of scientific enquiry and research. "Animals can't feel, dear," is a remark heard not infrequently from the more ignorant visitors at zoos even today, and this seems to have been the attitude in earlier times of scientists and research workers who certainly should have known better. Barbara Orlans does us all a service in reminding us of such depraved creatures as the anatomist Francois Magendie (1783-1855) whose work contributed much to the understanding of the nervous, venous, arterial and lymphatic systems; yet, long before the days of anaesthesia, he frequently repeated his excruciatingly painful dissections on living, fully conscious animals not to further knowledge but to demonstrate before audiences of his peers how enormously clever he was. Today, only the wholly pitiless could justify experiments on the eyes of rabbits, collared to prevent their scratching themselves, in order to ensure that some new eye-shadow or shampoo does not provoke allergic responses in targeted customers.

Yet if all use of animals for experiment is to be prohibited, as many so-called antivivisectionists demand, medical research is among the more important disciplines that will be severely hampered. Leprosy, for instance, is not the forgotten Biblical curse that many believe, but is alive and well, four million cases in India alone. Leprosy research has always been hampered because Mycobacterium leprae, unlike its close cousin the obliging and ubiquitous Mycobacterium tuberculosis, is unique to man, or was until recently, and cannot be cultured in vitro either. Only a decade or so ago it was discovered that the bizarre nine-banded armadillo of South-eastern America can be infected with leprosy, but the armadillo is scarcely the ideal laboratory animal. Then again this reviewer is among those people who have seen and touched a victim of raging smallpox -- a young Tamil fisherman in merciful, terminal coma, his entire body covered with seeping pustules. What would late 20th-century "animal activists" have done with Edward Jenner whose work rid our planet once and for all of that hideous scourge, but whose experimental animal was not an armadillo, nor a white rat, nor even a chimp, but a young village boy?

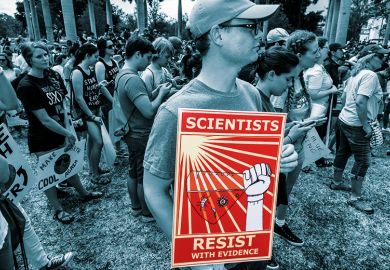

Orlans has done excellent service in showing that between those so violently opposed to the use of animals in scientific laboratories that they are prepared to place even the public in mortal danger through arson, bomb attacks or lethal assault on individual scientists, and those who believe it acceptable to subject animals to unimaginable suffering (as, for instance, in trauma research) for the benefit of mankind, there are not two but many shades of judgement. But in this book she has not tried hard enough, or has been unfortunate in her editors. Her index is inadequate; who on earth told her that macaques "are also known as rhesus monkeys"? And does she really think, as her list seems to imply, that Aids, rabies and hepatitis research are distinct from the discipline of virology? Moreover, it is difficult to pick up this otherwise scholarly work without the eye falling not on the Jenners and Jonas Salks of this world (neither of whom, nor their achievements, find mention), but on the monstrous cruelties inflicted by cosmetics research workers or contemporary Magendies. In the Name of Science is certainly cool and balanced, but it is hardly comprehensive. Finally, perhaps Orlans, though an American, will be charitable to an old-fashioned colleague who still believes that "author" is a noun and that books are written not authored.

Recently this reviewer, who lives in Madras and has a long- established reputation as a knowledgeable if amateur zoologist, received a panicky phone call from a stranger who said his verandah was swarming with leeches and that he was terrified for the safety of his children. I reassured the caller that the creatures he had seen were not leeches -- there are none on the hot dry plains of India, only in the damp and hilly forests -- and told him must be slugs. I also assured him that though slugs were a garden pest they could not possibly harm his children, and advised that if he wished to get rid of them a sprinkling of common salt was the simplest and surest remedy. Out of curiosity I asked him a few days later whether he had used the salt. My caller replied that since he was satisfied they were of no danger to his children he saw no reason why he should deprive them of their lives.

Such extraordinary compassion would be unusual even among "animal lovers" in the western world; indeed it comes as a surprise to be reminded by one of the authors in the collection of essays, Animals and Human Society, that even Queen Victoria was moved to comment that "the English are inclined to be more cruel to animals than any other civilised nations". The queen-empress might have been even more surprised to learn that aversion to animal cruelty was not unknown among her uncivilised, native subjects and extended even to less attractive invertebrates like slugs. Nevertheless the old queen must have viewed with deep satisfaction the disappearance of the English habit of cruelty to animals, for it was during her reign that the RSPCA rose and flourished, animal welfare generally became fashionable, as happily it remains by and large today, and that bull, badger and bear-baiting were abolished. Only decades later otter hunting became illegal too, yet "The English country gentleman galloping after a fox. The unspeakable in pursuit of the uneatable" (to quote Wilde) continues his eccentric, preposterous pastime. The more recent, sudden and dangerous appearance of the equally foul pit-bull terrier fighting was quickly put down, both by law and by justly horrified public opinion, though it may only have gone underground.

I recall my father describing how as a boy in Scotland he and other children would delight in the hilarious spectacle of pigs running squealing around their com£ after their throats had been cut to bleed them thoroughly before butchery. Does the brutalisation of children in this manner condition their developing minds to mete out similar treatment to their fellow men, particularly in times of war? That is certainly the collective opinion of the distinguished authors of this impressive compendium of essays on human/animal relationships. Religious testimonies, including Biblical, Koranic, Hindu and Zoroastrian concepts are quoted, with one notable contributor, Andreas-Holger Maehle, of the University of Gottingen, concluding that "treating animals carefully, respectfully and responsibly was the general conclusion drawn from the Christian concept of stewardship".

Yet few religious ideals approach that of India's Jains, who are not only vegetarians but will not eat any vegetable grown beneath the soil -- such as potatoes, carrots or onions -- for fear of destroying life-forms of any kind subsisting among them. The Jain community established a hospital for birds in Delhi but announced that the facility would not accept carnivorous, omnivorous or carrion birds: they could only be treated as out-patients.

These extremes characterise the human attitude towards animals in almost all cultures and religions through the ages, and the present collection of essays, recounting as the subtitle declares, our changing perspectives on other life-forms, is an excellent collection. It cannot be too strongly recommended for study by those in any way concerned with what have in recent times become lively and often ruthless and lethal campaigns for and against the various forms of our treatment of animals and our concept of their requirements, more often than not by pure and falsely anthropomorphic values.

From the austere and disciplined syntax of the above two books, we jump to the easier, more journalistic style of Stephen Budiansky's The Covenant of the Wild. But excellent as Budiansky's text undoubtedly is, his journalism is not quite what it might have been, for he has fallen into the obsolete habit of including lengthy, distracting footnotes containing material any competent writer could without difficulty have incorporated into the main body of the text. Then again, while he unnecessarily informs us the meaning of the acronym BP (before present) he later quotes the works of anthropologists still using the redundant Christian bc/ad, which has become even more tedious since adherents of other major world religions try hard to use dating systems that reflect their own religions and cultures. (It is worthwhile remembering the analogy that physicists, too, have dropped both the antiquated Fahrenheit and Celsius temperature measurements in favour of degrees Kelvin, which begin with absolute zero and can therefore never have ambiguous minus degrees.) While much else in this book is a rehearsal of well-known but ever wondrous examples of symbiotic lifestyles -- the hermit crabs and their portable anemones, the honey-guides, the ant/acacia symbiosis, the evolutionary advantages of animals flocking, and many more -- yet can we accept Budiansky's premise that animals actually chose domestication?

In the Old World we have many examples of domestication -- cattle, sheep, dogs, cats -- yet domestication seems to have escaped the megafauna of the Americas, densely populated by large mammals as they were before the coming of Stone-Age man just after the end of the last Ice Age, 11,000 years BP. Apart from giant sloths, mammoths, mastodons and many others, there were native American horses, but when a handful of mounted Spaniards arrived in the Americas ten millennia later they easily conquered Aztec, Maya and Inca warriors who might have been expected to expel them with cavalry charges -- had they ever seen or heard of horses. What happened to the native American horses? Like Antarctic penguins today, horses and other large American animals were relatively tame and were not "genetically programmed" to regard human hunters as enemies; probably also, as the ice receded, forests replaced the grasslands on which the horses had previously thrived.

Whatever the reasons, the American horse had become extinct many millennia before the coming of Europeans, whereas, as Budiansky reasonably argues, domestication would have saved them. The same is true of fowl such as the chicken, the duck, the turkey and the goose, yet it is difficult to accept this author's suggestion that all these species actually chose intimate association with man, that without domestication they would probably have followed their American cousins into extinction, and that "domestication was an evolutionary process not a revolutionary one, a gradual shift in inter-dependency rather than an inspired decision by cave-man". If so, why did it not happen in the Americas, where the first Stone-Age men -- arguably what are now called the Clovis hunter-gatherers -- could have taken similar advantage of the almost tame megafauna they found teeming in the New World?

Nevertheless, Stephen Budiansky's readable and plausible book, like the other two works under review, may with some success help clear the minds of "animal lovers" -- that odious misnomer -- who, defying all logic and reason, continue to confuse sentiment with compassion.

Harry Miller is a naturalist, journalist and author who has lived in South India since the 1950s.

Animals and Human Society: Changing Perspectives

Editor - Aubrey Manning and James Serpell

ISBN - 0 415 09155 1

Publisher - Routledge

Price - £35.00

Pages - 199pp