Source: Eleanor Shakespeare

On academic and pastoral matters, “any judgment of the courts would be jejune and inappropriate”. This statement was made nearly 15 years ago by Lord Justice Sedley in Clark v University of Lincolnshire and Humberside, one of the leading cases on how courts treat claims against universities.

Since then, courts have generally taken the view that they should not second-guess universities’ academic judgements, while universities themselves have adopted complaints procedures that typically limit students’ ability to challenge their grades. The Office of the Independent Adjudicator is also prevented by statute from hearing a complaint “to the extent it relates to matters of academic judgment”.

But there are obvious issues with this formulation. For example, what if, across hundreds of candidates, some decisions are reached on a different basis from others? What if examiners make a fundamental mistake which can be seen without considering the academic subject matter? What if the grade is treated as correct but a question is raised as to what follows in terms of retakes or expulsion? And what if a university fails to follow its own rules?

More recent cases suggest the sands are shifting and that, in an era when the student-university relationship is coming increasingly to resemble that of purchaser-service provider, courts are becoming more careful in their consideration of claims which are on the borders of this “academic judgment immunity”.

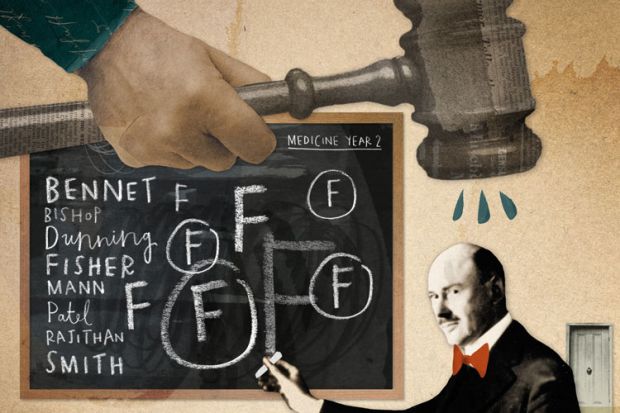

The most recent example is R (Gopikrishna) v OIA, on which the Administrative Court ruled in February. The claimant failed her second-year medical exams and the University of Leicester terminated her course on the grounds that there were insufficient prospects of her successfully completing the course. The university argued that was an academic judgement and the OIA upheld the institution’s decision on that basis.

The student argued that the decision-making process was unfair. The university panel was critical of her performance in her first year without hearing about her mitigating circumstances, and failed to follow the requirement in Leicester’s rules to consult her personal tutor.

The court found these failings of reason and procedure took the matter outside the realm of the academic judgement immunity, and struck down the OIA’s decision. The judge set out that the OIA has jurisdiction to hear a complaint involving academic judgement where that judgement suggests the existence of “procedural unfairness, bias, impropriety or the kind of administrative irrationality or perversity which the court can and does consider”.

The court has also been careful to distinguish areas within a decision that require academic judgement and those that do not.

This principle is well illustrated by the 2012 case of R (Cardao-Pito) v OIA, in which a student complained that harassment by his tutor led to his failure to attain the required mark. The judge recognised that marking was a matter of academic judgement, but he was clear that the effect of the alleged harassment on the student’s ability to write his research paper was not a matter of academic judgement.

The treatment of plagiarism in the 2013 case R (Mustafa) v OIA also demonstrates the distinction. A student was awarded zero marks when some of his research paper was found by plagiarism software to have been taken from other sources. However, although he did not use quotation marks, he did cite his sources in footnotes. The OIA deemed questions of plagiarism to be matters of academic judgement, but Mr Justice Males decided that this was not always the case. An example he gave was of a student who copies an entire article – no academic judgement would be required to see that this was plagiarism.

The courts have also been willing to consider claims for negligent teaching on the basis of expert evidence – as in other claims against allegedly negligent professionals. A good example is 2011’s high profile Abramova v Oxford Institute of Legal Practice, in which the claimant tried (unsuccessfully) to sue her law college, claiming that it did not prepare her adequately for her exams.

Of course, neither universities nor the OIA will find it easy to make fine distinctions about the borderline of academic judgement, and universities in particular will need to give their panels more access to legal advice to help them to define the issues from the outset. But there is no getting away from the fact that a claim of academic judgement immunity is no longer quite the trump card it once might have been.