It seems only fair and natural that the inventor of a vaccine that has made a major contribution to defanging a deadly pandemic should receive considerable reward for its efforts. Nevertheless, the meteoric rise of Moderna is remarkable for its impact not just on public health but also on the stock market.

Last year, the valuation of the 12-year-old Harvard University spin-out briefly touched $200 billion (£152 billion), soaring past that of long-established pharmaceutical firms such as AstraZeneca, Amgen and Merck, and placing it well above such household names as Coca-Cola (£67 billion), Ford (£76 billion) and General Motors (£129 billion).

“I’ve never cared about the valuation, even if [the $200 billion valuation] was kind of cool,” reflects Derrick Rossi, the Canadian stem cell biologist who co-founded Moderna in 2010 shortly after discovering a way to chemically tweak mRNA so it could be used to fight all sorts of diseases. “It was more compelling when the [Covid] vaccine was first approved for use so it could help people at the height of a global pandemic.”

THE Campus views: How to handle the jump from HE to a commercial venture

Moderna was the most spectacular success story among academic start-ups last year, but it was by no means the only one. Fellow vaccine pioneer BioNTech, set up by the University of Mainz-affiliated couple Uğur Şahin and Özlem Türeci, is now valued at close to £30 billion. Beyond the life sciences, the software company Databricks, which grew out of a research project at the University of California, Berkeley eight years ago, was valued at £29 billion last year, while the Swedish Oatly alternative milk brand – founded by a Lund University scientist – was valued at £10 billion in May after it was listed on the Nasdaq.

In the UK, several start-ups with their roots in academia also made headlines in 2021. Investors snapped up shares in the cybersecurity firm Darktrace, founded in 2013 by University of Cambridge mathematicians, when it listed in April, pushing its valuation to £2.2 billion. Meanwhile, the AI drug discovery firm Exscientia, a 2012 University of Dundee spin-out now based in Oxford, was valued at £2.5 billion shortly after its public listing in October.

The dizzying success of these academic “unicorns” – start-ups worth at least $1 billion (£760 million) – is an indication of the potential value in university discoveries. And while governments have for decades urged academics to do all they can to commercialise their findings, the urgency of that task is only ramping up further as nations scramble to become the “knowledge economies” that are expected to flourish as the fourth industrial revolution of robots and artificial intelligence unfolds.

In March, for instance, the White House gave the go-ahead for a long-awaited National Science Foundation division aimed exclusively at commercialising research findings. Meanwhile, the UK government has announced that it will increase funding to Innovate UK, its research commercialisation funder, by 66 per cent to £1.1 billion a year by 2025. It has also installed a former venture capitalist, George Freeman, as science minister.

Last month, Australia unveiled plans for a new research commercialisation fund, worth A$2.2 billion (£1.2 billion), to “fuse” the country’s “world-class” university research capabilities with the government’s “modern manufacturing strategy”. And the European Union last year set aside €10 billion (£8.4 billion) of Horizon Europe funding for a European Innovation Council to support the transition of promising ideas to market.

“Across the world, research institutions of all kinds are being asked a difficult question: ‘So what? You’ve had so much funding but what is your contribution to society?’” says David Ai, head of the London School of Economics’ innovation unit. Unicorns can easily respond to that question by quoting their market value, says Ai, who used to be a venture capitalist in Silicon Valley. However, “in different domains, we need to look at broader definitions of impact. Most mainstream venture capitalists have no interest in 95 per cent of the companies that the LSE starts, but that doesn’t mean they don’t have great impact.”

So is the understandable excitement about unicorns pushing policy and funding down the right path? Can we really learn much from a highly unusual era when a public health emergency raised the fortunes of a handful of companies to almost unimaginable heights at record speed? Might an obsession with creating commercial giants distract from the less heralded task of supporting basic research, or of nurturing small to medium-sized enterprises plugging less lucrative but still important gaps in the market?

“That Moderna became as big as it did was not shocking to me – we predicted early on that we should be able to turn this into a $100 billion company,” says Rossi. “That might sound a bit cocky, but, as someone who believed in the potential of this technology, I always believed it was achievable,” he says. “What I did not expect is that the first product would go to billions of people and play a particular role in ending lockdowns and, in some sense, saving humanity.”

The company’s original business model was to create a suite of drugs for treating specific genetic illnesses. With each drug having a global market of perhaps 100,000 patients, that would still have put Moderna on the path to greatness, Rossi says. And that belief is evidently shared by the firm’s current investors, who are looking beyond its $20 billion annual Covid revenues – and the 70 per cent decline in its share value since the $200 billion high.

“A successful biotech drug is worth $3 to $5 billion a year, so if you have 20 of these drugs then you could have $100 billion a year of income. To get five or six of these drugs gives you a $20 billion a year company. So our early thoughts were not unrealistic, even if every pharmaceutical company and his brother are now piling into mRNA,” says Rossi.

That level of ambition may partly be explained by the power of the research-industry nexus in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where Rossi continues to live. “This is the Mecca of the biotech industry – you have the academic institutions but also world-class intellectual property experts and venture capitalists looking to fund biotech,” Rossi says.

The Kendall Square life sciences hub “did not happen overnight”, however. And while something like it could be replicated in other cities with scientific strengths given the right investment, it wouldn’t be easy, says Rossi – who has also invested in several more life science start-ups since stepping down from his formal roles at Moderna in 2014. “[Kendall Square] used to be a bunch of seedy parking lots, places where you did not want to hang about. It started with a few anchor companies wanting to be close to MIT and Harvard. Sometimes governments try to pitch this as a way to revive a town down on its luck, but you won’t get the meetings you need to happen there.”

The ecosystem around the University of Oxford in the mid-2000s was crucial to the success of DNA sequencing company Oxford Nanopore, which was valued at about £4.8 billion shortly after its flotation last September, says Hagan Bayley, who co-founded the company in 2005.

“As things moved along, the university had a really good tech transfer office and was very useful in terms of intellectual property and seed funding,” says Bayley, who still works as a professor of biochemistry despite pocketing a reported £32 million windfall from last year’s flotation. However, the “enormous effort” of bringing science from lab to market should not be overlooked, he adds. “In universities, we like to think the research is 90 per cent of the work and companies do the other 10 per cent” – but, in reality, “perhaps what we do is the easy part: things that just happen to work out for us in the laboratory”.

But he does not think that universities should be involved in commercialisation, and he worries that the growing emphasis on financial returns rather than fundamental science will backfire for UK science. “You can see this with vaccines,” he says. “The big drug companies with research budgets of £5-10 billion didn’t come up with much. The real innovations came from universities.”

In his case, “we didn’t set out to create a billion-pound company – we were thinking in terms of how our platform technology for single molecule sensing might work. We knew we had a world-changing technology, but it took seven to eight years to get to the point where we could use it.”

Similarly, it would be a mistake for governments or funders to attempt to directly engineer multimillion-pound companies, says Bayley. Rather, they should take the long view: “We can facilitate commercialisation, but only if there is new science to commercialise – and the UK is very good at this fundamental research. All these ideas that research should be focused on impact fail to take account of the serendipity that important science requires – if we have curious scientists who are well funded, that would be best for UK science.”

Former UK science minister Lord Willetts is also wary of the stampede for commercialisation.

“We create too many tiny spin-outs that hit the market too soon – some research projects should remain research projects,” he says, warning against “counting the number of companies” that universities create as a measure of their success. However, he welcomes the government’s increased support for research commercialisation, believing that it will give more time for researchers to develop businesses based on their results.

“Historically, public support for research has stopped too soon on its journey to market, so the reversal of [previous] big cuts to Innovate UK is very welcome,” says Willetts. He also praises the formation of a new ministerial council for science and technology, headed by prime minister Boris Johnson, which he hopes will encourage more strategic cross-government thinking about science investment. “There is a transformed way of thinking about science – with the council trying to pull it all together,” he says.

One key area that might come under review is intellectual property (IP) rights, says Willetts. While some institutions might argue they should share in the success of a future unicorn, that desire to stay in the picture is likely to harm a start-up’s chances of making it big, he explains. “British universities are terrified of a start-up being successful if it means having to explain why they only have 5 per cent or less of the company,” says Willetts. “The US is much more grown-up about this – it’s sometimes said that MIT actually makes more from T-shirts than it does from its spin-outs.” Whether that story is apocryphal or not, MIT is estimated to have been the genesis for more than 26,000 companies, with a current combined annual turnover of £1.5 trillion – roughly 60 per cent of the UK’s annual GDP – according to the Kauffman Foundation.

Universities can make very bad major shareholders, adds LSE Innovation’s Ai. “Sometimes universities in the US have invested early and done quite a lot of the heavy lifting to get a company off the ground, so will want to keep 30 to 50 per cent,” he explains. “But a company might need to fire its CEO overnight or respond to a takeover offer in a matter of hours, so it can’t wait around for university committees or councils to make up their minds. Universities should ask what they’re adding to the spin-out, or whether they are deadweight, making the company seem like a bit of a dinosaur in the commercial world.”

That view is also endorsed by Chris Loryman, senior manager at the University of California, San Diego’s commercialisation office, which in recent years has helped companies started by San Diego academics to raise almost $9 billion in investment.

“IP policies at universities absolutely make a difference,” he says. But he agrees that they should not be drawn up with the idea of maximising university revenue. “The notion of universities funding themselves in a meaningful way via licensing or start-up activity is ridiculous and dangerously naive,” he says. Having previously worked at several London universities, he describes UK universities’ “obsession” with making money from commercialisation as “unsophisticated, pre-industrial and self-damaging”. He suggests that Parliament change the law to limit how large a stake universities can take in spin-outs.

So what is the answer regarding IP? For some, Sweden’s “professor’s privilege” – the right of academics to fully own the IP of their research, inventions or patents – explains a lot of the country’s phenomenal business success in recent years. With higher financial incentives, it is claimed, academics naturally seek to become more entrepreneurial. And that mindset filters through to students, resulting in Stockholm’s thriving graduate start-up scene – responsible for firms such as Spotify, Skype, the fintech firm Klarna, Minecraft owner Mojang, and King, the company behind Candy Crush.

“Researchers are the ones who will drive a project forwards, with their networks and knowledge,” explains Marcus Holgersson, associate professor at the entrepreneurship and strategy division of Chalmers University of Technology in Gothenburg. “Without the professor’s privilege, it can be difficult to get researchers on board.”

The professor’s privilege was introduced in Sweden in the 1940s, and was also common in several other European countries. Holgersson, who was recently tasked by the European Commission to review IP practices in European universities, says evidence of the privilege’s effectiveness can be found in a 2016 study, which found that the number of university start-ups and patents in Norway both halved shortly after the country abolished its own professor’s privilege in 2003, in pursuit of US-style commercialisation success. In Norway, universities may now claim as much as two-thirds of commercialisation income rights.

But allowing staff to retain the full IP rights and royalties to their research can throw up problems too, says Lisa Ericsson, founder and head of KTH Innovation at KTH Royal Institute of Technology, where Times Higher Education’s 2022 Innovation and Impact Summit is taking place from 26 to 28 April. This is because individuals can sell their future IP rights to companies in exchange for funding.

“The rights for that individual’s entire career could belong to a company,” explains Ericsson. “The researcher might be happy to do this, but it can make things difficult when it comes to working with other universities or laboratories in future.”

The rise of a whole new wave of private investors in individuals’ future IP rights – including the not-for-profit Arcadia Science and New Science and the for-profit Molecule Dao – makes it more important than ever that researchers do not sign on the dotted line without taking proper advice. That is particularly true given that some industry investors may seek to acquire rights to research and ideas for the very worst reasons, warns Oxford Nanopore’s Bayley. “Big companies can buy smaller ones to shut them down because they are using competing technology – we consciously avoided selling the company or technology because we didn’t want anything like that to happen,” he says.

Ericsson’s office at KTH, whose alumni body includes the founders of Spotify, Skype and software company Databricks, contains two patent attorneys and an IP lawyer to advise researchers on such intricacies. Her team also spends time educating PhDs and postdocs about the basics of patents and licensing. In some cases, KTH Innovation will hire a chief executive to run a promising university spin-out so that the academics can return to the lab. It may also recruit a PhD graduate to further develop a business case, in the hope of attracting private investment. “Through our investment arm, we can also give them an investment offer ourselves – and we will try to invest in those that we think can get big,” says Ericsson.

But the Stockholm university is equally willing to get behind ideas at an early stage, when it is not clear whether a viable business will emerge. In partnership with Sweden’s innovation agency, Vinnova, KTH provides proof-of-concept grants of up to €30,000 to allow staff and students to develop or finesse a prototype based on their research – which, according to Holgersson’s recent EU report, bridges a “small death valley” for start-ups that industry investors view as still being too risky to spend money on.

“It’s not about making money for us,” says Ericsson, whose department has supported more than 3,000 ideas from students, staff and entrepreneurs since 2007, including more than 1,000 from academics. Those companies have employed almost 2,000 people, raised £20 million in funding and generated £4 million in tax revenues. “It’s about creating value and impact for the university, which is able to attract students from abroad because they hear about our work and want to become part of the Stockholm ecosystem,” says Ericsson.

That mix of the right IP policies and financial support is important for commercialising research, but governments could go even further, by way of procurement and regulation, says Naomi Weir, director of innovation at the CBI. “In the UK, we have some areas of strategic advantage, such as space or aerospace…but we may be putting the brakes on them through things like overly rigid procurement procedures,” says Weir, referring to the fact that smaller UK start-ups may be turned down for government contracts in favour of large multinationals that are more experienced in jumping through the bureaucratic hoops.

She says the prime minister’s new science council is well placed to coordinate and drive these efforts across Whitehall. “The government could also think about its role in regulating markets so that businesses must become more energy efficient – which could benefit companies based on novel technology developed in universities,” she says.

Finding ways to incentivise the “right investors” to back the “more deep-tech-oriented university spin-offs” for reasonable durations is perhaps the biggest challenge for university spin-outs, says Ericsson. “It has been quite easy to raise capital, both in Stockholm and London, but venture capitalists who are very experienced in digital companies are often not long-term funders…and therefore not very suitable for investments in companies with a longer time to market,” she says. “There is a clear need for more patient capital in more evergreen structured funds that understand deep tech and have the time and funds to be part of the journey.”

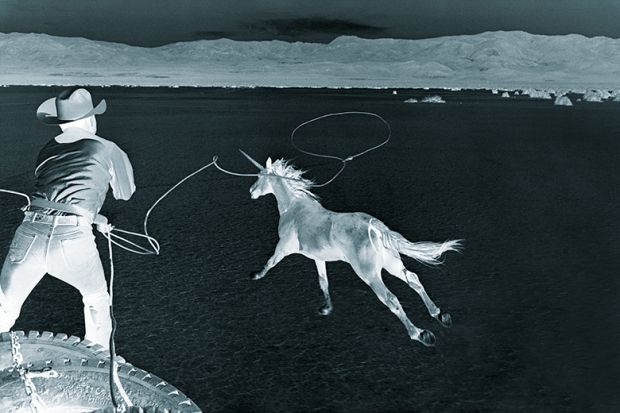

Even then, however, university-spawned unicorns are likely to remain almost as rare as their mythological brethren. And by the time they acquire their horns, they are likely to have long left behind the university stable.

As California’s Loryman puts it, “Flashy IPOs happen from time to time, and, yes, some of those companies have a heritage back to a university. But the reality is that these $1 billion companies are one-in-a-thousand and usually decades in the making. That’s not what university-derived companies generally do – and nor should they seek to.”

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Is chasing unicorns the way to achieve commercial success?

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?