On a typically boiling mid-week afternoon last year, two fellow university lecturers and I were sitting in mutual perplexity under the campus pagoda of a UK-validated university in the Middle East.

A well-respected manager at the university had been unilaterally using his faculty’s website to advertise programmes that did not exist in a desperate effort to get prospective students through the door. He succeeded in that respect, but the programmes – highly technical in nature, requiring UK validation, as well as new staff and equipment – had yet to materialise. Now the parents of those students were on campus, lividly demanding to know how the futures of their children could be treated with such disregard.

Not for the first or the last time, we were astounded by the gap between what we understood as best practice and even legality in a UK context and the realities of the partner institution we worked for, with its own embedded sets of practices, structures and characters, some of which brought about occurrences of this magnitude far too frequently. Working abroad, we had all expected to encounter cultural difference and to have to adapt our practice to locally specific expectations. But this was not cultural difference, it was gross misconduct.

So how had I found myself in this situation? Coming to the tail end of an employment contract in the UK, I had begun once again to peruse academic job sites. Thumb-scrolling my phone in a Liverpool pub, the rain pouring outside, there rolled on to my screen a posting that seemed outlandish at first sight, even laughable, in a MENA-located faculty that was less than a decade old. A pint later, though, I reflected that I had always wanted to use my PhD to travel, especially considering the trajectory of the UK academic jobs market and, indeed, the country itself, which seemed to have been pushed by Brexit and Covid into a countrywide phase of normalised panic and social disintegration.

I began looking at pictures of the city where I would be based and fantasising about hot weather, adventure, a dependable salary and some respite from the madness. I looked up the university, too. There was no detail on the programmes offered in my field, and I wondered how its prospective students were supposed to obtain this information, but I went ahead and submitted a boilerplate CV and cover letter before promptly returning to the real world.

Two months later, I received an invitation to interview online for the role. At the appointed time, I logged on and was greeted by three suited men in what seemed to be an office made entirely of gold. We began the interview, but halfway through their internet dropped. I soon received an email from the university requesting that I write down the rest of my answers and submit them. The problem was that I hadn’t received any questions. So, once again, my head was back in rainy Liverpool, slightly confused but thinking nothing of it and trying to focus on getting a “real job”.

To my surprise, I was invited for a “second interview” a month later. I was even more astonished when this turned out instead to be an offer of employment. I sat in front of the laptop screen trying to look unperturbed as a stranger from HR described my imminent relocation to the Middle East.

Of course, I had my doubts. At that point, my main concern in a professional sense was that I would lose contact with UK colleagues, and that this move might somehow be perceived by my peers as an acknowledgement that I could not “make it” in the premier league of UK universities. But after a number of conversations with UK colleagues who were already working there, the idea of joining them gradually became real to me. And, after all, weren’t my doubts about perceptions of inferiority just manifestations of a neocolonialism that we should all know better than to indulge. So, ultimately, I accepted the offer of a lectureship contract.

I would soon discover, though, how flippantly the term “neocolonial” can be used as a way of shrugging off the genuine complexities of transnational education (TNE).

TNE allows overseas students to obtain a UK degree by studying in their own countries. In recent years, it has been valued by the UK government as a way to access international student markets while potentially reducing the number of international students within UK borders. To see it in those mercantile and politicised terms is a shame because it deserves much more serious discussion, and it is obviously detestable (dare I say neocolonial?) to use international students’ lives and hopes for the future as a political football. But there is no question that TNE is a money-spinner for UK higher education.

According to recent data from the Higher Education Statistics Agency (Hesa), overseas instruction generated an income of £2.3 billion for the UK in 2020, an increase of 112 per cent since 2010. That is a drop in the ocean compared with the £42 billion contributed to the UK economy every year by international students within the country, but if the political pressure to reduce net immigration results in more restrictions on students, it may be that TNE partnerships become more sought after. In any case, clearer guidance on quality maintenance and the formation of “equitable partnerships” is desperately needed.

Educating more than 500,000 students across 228 countries and territories, UK TNE takes a range of forms, from fully fledged international branch campuses (IBCs) to more tentative franchising, licensing and programme-validation agreements (known as collaborative provision). For instance, the majority of provision across Africa is collaborative, such as dual degrees that are recognised in both the host country and the UK.

However, it is essential to acknowledge that policy landscapes in host countries will continue to shape the possibilities for UK TNE partnerships. According to the British Council, the leading UK TNE provider in Africa is Egypt, but the Egyptian government is especially keen on the development of IBCs given the country’s urgent need for foreign investment and its construction of satellite cities around Cairo that will need higher education provision. But while the route to establishing IBCs is being smoothed, the laws governing longer-standing practices of collaborative provision remain unclear.

In short, TNE policy is a grey area in many countries because of the complex tangle of interests and procedures involved in melding different legal frameworks together across sometimes vastly different cultural-practical understandings of how to do university education.

Given these overlapping rules and responsibilities, as well as difficulties of establishing smooth working relationships between distant and very different institutions, the potential for disaster is clear. I have seen universities steam forward with the validation of programmes in overseas faculties of which they have little to no practical, day-to-day working knowledge. Sometimes these are places exhibiting a host of standards and practices with which I am positive no UK institution would wish to be associated, including no-fault summary dismissals, shocking treatment of women, and fealty to power as the central underpinning of teaching and learning strategy. Yet the UK institutions remain gleefully ignorant of these as long as the validating documents read well, and the yearly “link tutor” meeting passes without a fuss.

Link tutors are staff members from UK universities who have been nominated as the primary point of contact for programmes administered overseas by the host organisation. Their role is to ensure clear communication between the two parties and to work closely with partner organisations to maintain quality standards. Once a year (typically), they fly to the host country to meet staff and students. In essence, these are monitoring exercises that supposedly ensure a high standard of teaching and learning on validated programmes. For many link tutors, however, these international quality assurance duties are tacked on to their existing workloads, and their vigilance is blunted by the fact that it is difficult to care about standards in a distant country when you have more immediate domestic concerns.

More fundamentally, genuine quality maintenance would often boil down to a bemusing process of figuring out where cultural adaptation of programmes ends and bad practice begins. In reality, ceremony and social media posts have become the simulacra of successful partnerships.

My own experience can be characterised as a slow dawn, beginning with the first module guide I was asked to rewrite and teach. It was an introductory module that had been created by a previous staff member (staff turnover was ridiculously high, it turned out), yet it pointed towards a PhD level of instruction on a highly specific subject area, not a general introduction more suitable for first-year students. The staff member had simply transported the contents page of their recently completed thesis into a module guide format and proceeded to teach their PhD to a class of first-years, who were required to complete 15 separate assessments to pass the module, none of which had any bearing on the stated learning outcomes.

I never asked how this module had been validated. I had just arrived in the country and did not want to be seen as a snobby colonialist. In hindsight, it points to the fact that many staff members in UK-validated overseas universities are drawn from the better regarded public universities of their own countries, so have zero knowledge of the UK university system. Moreover, they are often on secondment from those universities and view their secondary roles in the private sector as facilitating “easy education” for students who lacked the grades to win a place at a more demanding public university: a task requiring zero effort from tutors. At the time, however, I marked module guide writing as an area in which I might help the faculty to develop and improve, recognising that in this country things were “done differently”.

Of course, however, the problems are much more complicated, and my optimism eroded as time passed. I was often left nonplussed as I discovered that the students I was attempting to lecture could not speak English. Given that our institutional language of instruction was advertised and celebrated as English, I wondered how these students had gained entry to this degree programme – and, more immediately, how on earth they considered it passable. I had an English-speaking student translate this question to one of their peers, who smiled as if their presence on the course was a case of superficial mischief instead of a fundamental problem. This student knew, way better than I did with my lack of local understanding, that in this place it was easy to obtain a UK degree without knowing English.

It soon became easy for me to identify the blank expressions of students who had almost no idea what I was trying to teach them. Yet the problems ran even deeper. Consider the lure of an “easy education” in a cultural context of overriding fetish-credentialism and a country enduring multiple, ongoing economic shocks. Institutions may adapt to conditions such as these in ways that undermine quality and threaten reputations. There are cases in which faculties have been encouraged to surreptitiously lower or even waive entry requirements without notifying UK validators. I worked alongside many great people overseas, but in most cases their actual roles were reduced to putting out fires created by inexperienced staff who encouraged such unsatisfactory practices. Many hires were, for example, recruited from the oil and gas sector or the military.

This made it all the more difficult to apply and maintain UK policies and regulations in the lecture theatre. Other problems – including the recruitment to non-existent courses I described above – emanated from departmental leaders who seemed to understand their positions as something akin to that of dukes, with each faculty an individual fiefdom built to serve their personal interests.

There were staff members and teaching assistants who, partly through their fealty to power and partly through their lack of basic knowledge and experience, curried favour with their duke by doing whatever they were told (sometimes acting in nefarious ways). Such people were bestowed with grandiose but empty titles that they could advertise on social media and in their email correspondence. I received multiple messages from individuals with titles such as “teaching assistant and international partnerships coordinator” and “lecturer and executive director of marketing”. In one incident, I offered a word of caution to a “professor” who had given her entire cohort of 50 students a first-class mark on a single essay assignment, with the lowest receiving a grade of 80 per cent.

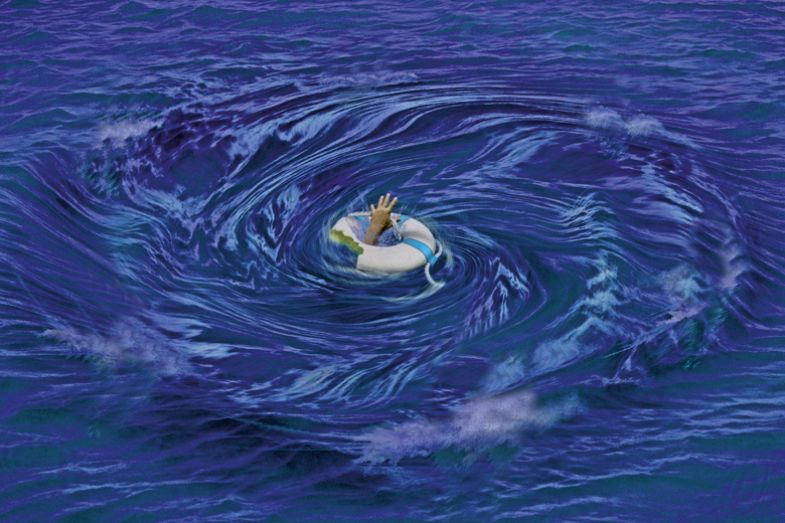

When my contract was up, I learned that it was not being renewed. My initial reaction was a familiar sense of alarmed perplexity, but that was soon washed away by relief. At least I no longer had to spend my days under that pagoda in a state of bewilderment.

Our UK link tutors during this time were broadly aware of some “issues”, but they were oblivious to their scale and depth. Link tutors are often course leaders who have a deep knowledge of their own programmes and are therefore capable of addressing questions from overseas staff during their scheduled meetings. The problem is that they rarely have a deep knowledge of the institutional culture of their TNE partners. Having previously worked as a link tutor in a UK university, I myself was unaware of the extent to which staff in host institutions could maintain a smile while the building around them burned. This is partly out of professional embarrassment and partly out of a perspective that views link tutors as representatives of institutional sponsors rather than international collaborators.

Moreover, it is often very difficult for teaching staff in host countries to be honest with their UK TNE partners, lest any criticism be seen by their managers as a personal attack that warrants revenge once the link tutors disappear. In some places, one-year contracts have become standard for this very reason.

This points to deep cultural and structural issues that are hampering TNE discourse. Link tutors’ reports are often ignored over many years, especially when they highlight issues that are difficult to address. In one instance I am aware of, for example, the delivery of a particular module was predicated on the use of a piece of equipment that customs would not allow into the country because of suspicion that it could be employed to counterfeit money. There was nothing that staff on either side could do about that, so after a while it just became a longstanding joke.

Establishing an independent third-party organisation to maintain quality in TNE, as recently suggested in Times Higher Education by the University of Greenwich scholar Michael Day, is an interesting medium- to long-term solution. Yet I would advocate for the building of more immediate, day-to-day relationships between staff across institutions, including staff exchange programmes and sponsorship initiatives for colleagues who wish to gain knowledge and experience of international education contexts.

But if we are serious about developing equitable TNE partnerships, it would help if link tutoring was given more institutional resource. Instead of having link-tutor responsibilities tacked on as afterthoughts to more pressing domestic responsibilities, link tutoring should be a role in itself. Subject-specific staff who are engaged in link tutoring should be seen more as diplomats: experts on the country they are working in as much as on their own fields. Many of the smaller but festering problems I witnessed could have been ameliorated through cultural diplomacy, but this requires the time and resources for UK academics to develop genuine working relationships with their international peers.

I made some lifelong friends during my two and half years abroad. I also gained a deep knowledge of my host region, and this has led to fruitful research collaborations that will continue to play a significant role throughout my career. However, the experience was soured by frustration, estrangement and institutional isolation, and I would advise anyone thinking of taking up a TNE position abroad to do more research and think more carefully than I did.

You should pay much closer attention to the interview process, for instance, and consider what it tells you about the host institution. You should also reflect on how exactly the position will progress your career. One of the main risks is coming away from the experience feeling like you’ve accomplished nothing, but devising a series of place-specific goals on a timeline that runs to the end of your initial contract can help to maintain a sense of coherence and finitude. Think about what the host country can offer you in terms of developing original research and teaching, then work to those specifics.

It’s also important to have an exit strategy up your sleeve because the host country may be subject to rapid changes that make your position less viable, particularly as you may have fewer employment rights and protections there than you do at home. If, for example, global events trigger a sudden economic shock, you may be let go no matter what the terms of your contract stipulate. Indeed, a key lesson more generally is not to consider those terms to be binding on your employer to the same degree as they would be on a UK employer. Prior research on the host country’s working environment will also help you anticipate unfamiliar teaching and learning situations.

However, no amount of pre-emptive research can take the place of personal experience – and that experience can be professionally useful. Towards the end of my “TNE journey”, I began to view my job as more of an ethnographic research project, with a view to future publications, than a teaching position. This perspective became crucial to alleviating my disillusionment with the institution. More importantly, it made it easier to get out of bed during a difficult period of my life.

The point here is simple: try like hell to derive something positive from your experience. Indeed, that is precisely what I am trying to do by writing this article. TNE can be tough going, but the more that people with direct experience of it shine a light on its flaws, the more chance there is that institutions will set their minds to rectifying them.

Anthony Killick is currently a sessional lecturer at Liverpool John Moores University.

后记

Print headline: Off-brand enterprises