Some Indian scholars like to joke that it’s easier to get into Harvard than into an Indian Institute of Technology. Various complexities of the system make it hard to confirm that claim definitively, but admission rates at India’s most highly regarded institutions of science are certainly in the single figures and, in some cases, appear, if anything, to be even lower than Harvard’s 4 per cent published rate.

For many Indian pupils, the desire to gain entry is difficult to overstate, says Ravinder Kaur, a professor of sociology at IIT Delhi. “Anything that happens in IITs becomes headline news in the country. They’re so large in the Indian parental imagination; every middle-class Indian would like to send one child to an IIT.”

It is not hard to see why. The universities are not only powerhouses of technical research and education; IIT graduates have gone on to top jobs in many sectors, landing coveted positions in India’s civil service, founding start-ups and leading large Indian companies. Well beyond India, too – from Silicon Valley to Wall Street – these institutions’ alumni abound.

But is the IITs’ near-magnetic attraction justified? In such a large country, with so much talent to draw on, are they maximising their potential and creating a supportive environment for their highly diversified student bodies? And where do they go from here?

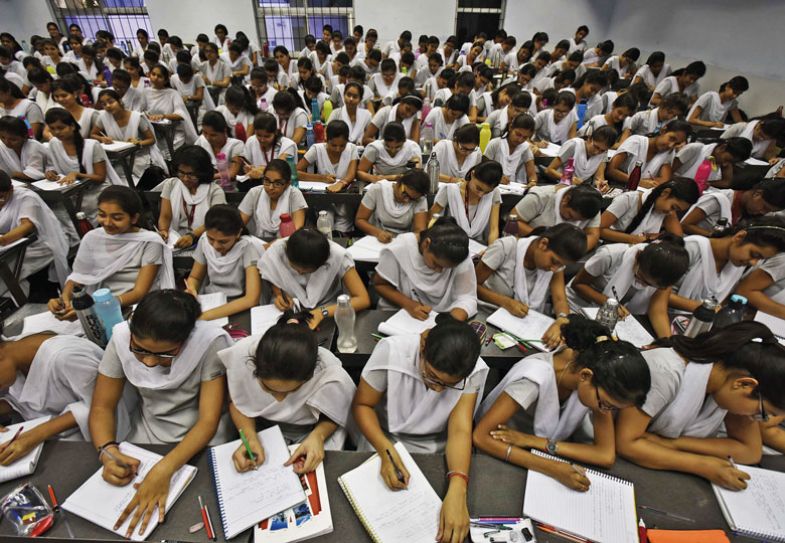

Each year, hundreds of thousands of Indian pupils sit the common entrance exams for the 23 IITs – which, in 2022, admitted only 16,625 undergraduates between them. For this reason, cram schools have proliferated in recent years to such an extent that the economies of whole cities, such as Kota in Rajasthan, revolve around them.

That line of work was boosted in 2007, when, faced with the impossibility of hand-grading hundreds of thousands of tests, officials made the exam multiple choice. This move has turned IIT entry into “one big gaming scheme”, says Anurag Mehra, a professor of chemical engineering at IIT Bombay.

“The IIT system makes you very opportunistic in a very basic sense. You just want to do very well and bag the best job,” he says.

That can lead to some disgruntlement among IIT graduates – and their parents – whose high professional expectations are not fulfilled. “Everybody thinks IITs are a ticket to fabulous salaries,” says Kaur. “The less talked-about stories are how many people don’t get great jobs.”

More seriously from an educational point of view, Mehra worries that the cramming culture is a poor preparation for the kind of critical thinking required of IIT students. Back when he was finishing high school, coaching was already entering the scene, but it was not yet an “obsessive thing”, he says. Moreover, the IIT entrance test that he took, involving a long paper based on Cambridge-style essay questions, was a world away from today’s breakneck multiple-choice marathon.

“Today’s students are not equipped to formulate problems or be original in any sense,” Mehra says. “School has not taught them that; coaching has not taught them that. I think…people don’t want to admit it. It’s like saying we’re not that good after all.”

Perhaps equally bad, students often choose their discipline based on its prestige – the more selective, the better – and the size of salary it is likely to yield, rather than out of any genuine enthusiasm for it, he says. “Very few people are interested in their branch…Everybody wants to get into highest branch in the list”, with the greatest preference being for computer science, followed by electrical and mechanical engineering. “So many students are in branches where they have no aptitude or interest.”

Pankaj Jalote, founding director of the Indraprastha Institute of Information Technology – the so-called triple IT, though it is unaffiliated to the IITs – agrees that there is a “herd mentality” among the students, with many of them already “burnt out” before they enter campus.

“With such intense competition, when they get in, students have already achieved what they set out to do, so [faculty] have to try to convince them that this is the start of their education, not the end of it,” Jalote says.

This view is shared by Preeti Aghalayam, professor of chemical engineering at IIT Madras, which is also her alma mater. She says the perception of admission as an end-goal – combined with years of relentless coaching – has led to a “negative attitude” to education among some students. But she disagrees that IIT students today are any worse than ones like her, who studied in the 1990s: “These are really smart kids, but because of the way the system is and societal pressures, it’s IIT or bust. Many of them get forced into this.”

Recent high-profile suicides have also drawn scrutiny to mental health issues among students. Last month, the education ministry revealed that 39 IIT students died by suicide between 2018 to 2023.

For Swati Patankar, professor of biosciences at IIT Bombay, today’s students are no less eager than previous generations were to embrace critical thinking, but they can take a while to acclimatise after years of learning by memorisation.“As soon as you show them there’s something more interesting than that, they love it – they’re delighted they don’t have to do multiple choice any more,” she says.

Naviket Mankoo, an engineering student at IIT Ropar and its student council president, agrees. The wide variety of student debating clubs and student societies on campus are testament, he thinks, to his classmates’ genuine intellectual curiosity. He says that despite the bad rap it gets, the infamous IIT entrance exam requires test-takers to have better reasoning skills and more creativity than they get credit for. “The approach you need to follow is quite critical, I think,” he says.

Moreover, IIT dropout rates are declining rather than expanding, from 2.25 per cent in 2015 to just 0.68 per cent in 2019. That fall was the result of “a number of corrective measures to minimise the dropout”, then education minister Ramesh Pokhriyal told India’s parliament in 2020. These “include appointment of advisers to monitor the academic progress of students and peer-assisted learning”.

Still, when the Ministry of Human Resource Development announced in 2019 that 2,461 students had dropped out in the previous two years across the 23 IITs, one admissions tutor described the figure as “a huge and unbelievable number, given the number of applications that we get each year”.

The students who do make the cut have traditionally opted for more technically focused majors. Ask students what kind of degree they’re getting at an IIT and you will most likely hear “B-Tech” – Bachelor of Technology. But interdisciplinary studies are gaining ground. India’s 2020 National Education Policy states that a “holistic and multidisciplinary education…is what is needed for the education of India to lead the country into the 21st century…Even engineering institutions, such as IITs, will move towards more holistic and multidisciplinary education with more arts and humanities.”

While disciplines are “still quite siloed” at the IITs, more flexible programmes of study have entered the scene in the past seven years, with the emergence of “minors” – second specialties – 15 years ago. And although STEM disciplines remain the staple, these days more students choose to major in the humanities and social sciences.

“Ten years ago, the humanities used to be referred to as ‘service sections’,” a term that denoted their relatively peripheral status, recalls Mehra, who completed his bachelor’s at IIT Kanpur. “They would teach you that Shakespeare existed…but not much else. In IIT Kanpur’s case, there’s been a very clear debate on how to enmesh the social sciences and humanities into the STEM focus,” he says.

IITs’ interdisciplinary centres have also taken off, with hubs in machine science, data learning, biology and medical applications. Newer IITs have sometimes started with these centres in lieu of conventional programmes.

IIT Delhi’s Kaur says that slowly, institutional heads are coming to see the value of a more rounded approach, though she notes that there can sometimes be pushback when colleagues in the non-STEM fields question the findings in the sciences – something that “may not be so easily acceptable to engineering and science professionals”.

In some instances, change has proved slow to catch on. A liberal arts programme being brought in at IIT Bombay allowing students to “customise” their degree by combining courses in a variety of subjects was met with resistance by students, says Mehra: “Any time you tell them this is a liberal arts way of doing things, they [question] if it’s good enough or not.”

In hard sciences, too, there are areas where IITs are struggling to catch up with the times. For instance, these institutions continue to lag behind on creating links with industry, says Jalote, who was previously a chair in the computer science department at IIT Kanpur and a professor in computer science at IIT Delhi. Back when he did his first sabbatical from IIT Kanpur, at the IT company Infosys, he was “probably one of the first” of his colleagues to spend the time in industry rather than another academic post. While more academics are crossing over into business today, the number remains “still very small”, he believes.

Founded in the 1950s, the earliest IITs were “forward looking” for their time, says Ramgopal Rao, director of IIT Delhi from 2016 to 2021. The original five – IIT Kharagpur, built in 1951, followed a few years later by IIT Kanpur, IIT Madras, IIT Bombay and IIT Delhi – were created through an act of parliament, the same process used to create the Ministry of Education.

Each of these institutions received support from a foreign country with finances, governance structures and faculty. IIT Kanpur, for instance, was modelled on the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, while IIT Bombay was created in partnership with the government of the Soviet Union – giving each institute a distinctive culture. While some of these differences have faded over the decades, some original “flavour” remains, says IIT Bombay’s Mehra.

“IIT Kanpur is very American. Students are much more confident…when I arrived at IIT Bombay, I asked students, ‘why are you guys so mild’,” he jokes.

Today, following the addition of another 18 IITs in the early 2000s – in turn mentored by the older IITs – the atmosphere at the institutions is more likely to be determined by “local factors”, Mehra says.

Crucially, though, all these universities share a common thread. They have enjoyed a large degree of autonomy from the outset. Unlike India’s federal and state government-run universities, IITs don’t answer to the national oversight body, the University Grants Commission. The UGC chair is a member of the IIT Council, to which each individual IIT’s board is answerable, but the council also includes the chairs and directors of the individual institutes, as well as the minister and various other political appointees and sector body officials.

Jalote says this “separation of powers” was something he sought to emulate in the IIIT. “In a regular university, the [government-appointed] vice-chancellor is chief executive but also chairs the board, so the board is not an independent power,” he notes.

In Jalote’s opinion, the IITs’ autonomy has become even more important in recent years; in the past half century, it has insulated institutions from political interference at a time when “many great centres of learning seem to have declined”. Critically, IITs’ hiring and promotions have remained free from outside meddling, allowing merit-based selection for “the best” researchers and teachers and a “culture of openness” with greater exchange of ideas between scholars, he says.

That independence has also helped keep the curriculum fresh. While courses must be approved by a faculty senate, there’s a lot of room to innovate, says Kaur.

“I think it makes a big difference,” she says. “I can literally reinvent my course every semester, so updating can happen seamlessly. You’re not stuck with outdated readings, which often happens at other universities.”

Judging by student feedback, too, the flexibility has come as a boon. Mankoo, IIT Ropar’s student council president, feels students are generally heard when they raise problems: “Our administrators are very supportive. There are not any sort of tensions where we as a student community have been on opposite sides…There’s always a sort of negotiation.”

Sanskar Soni, secretary general of the Student Affairs Council at IIT Delhi, agrees. He says there have been some contentious issues lately, such as the establishment of visitation hours in male- and female-only hostels for those of the opposite gender – already the norm at some of the other IITs. But he’s optimistic things are headed in the right direction.

“There’s always disagreements,” he says, “but that leads to better results.”

In other ways, too, IITs have changed with the times. In recent years, they’ve put a greater emphasis on graduate students and research, says IIT Madras’ Aghalayam: “Back in the ’90s when I studied, IITs were predominantly undergraduate institutions. In chemical engineering, we had only one or two PhD scholars doing research in each lab…now, that is completely stood on its head.”

Currently, only a third of IIT Madras students are undergraduates; by contrast, it has more than 3,000 doctoral candidates, with each faculty member advising roughly five PhD students and research occupying a “very large fraction of our time”, she says. The “look and feel” of the institution has also been upgraded, with an emerging start-up culture and new, sophisticated research laboratories replacing older teaching labs.

Perhaps most noticeably, though, the number of students at IITs has greatly increased, thanks largely to extensions of India’s “reservation system” – its extensive legal framework for affirmative action, which opened more seats for certain disadvantaged groups. Aghalayam’s own undergraduate class, for instance, had 45 students; now, it has 120.

The increase is mirrored at other institutions. IIT Delhi, which for decades maintained a student body of 4,500, now has upwards of 12,000 (including postgraduates), with more diversity than ever before. Currently, more than half of the seats at IITs are reserved for disadvantaged groups.

As Kaur puts it: “When I first started, there were basically privileged people sending their kids to the IITs…Now, a lot of students come from small towns and rural India; a lot of them have studied in regional languages before coming to IITs.”

Women, too, are better represented among undergraduates. Female students now account for 20 per cent of B-Tech students at most IITs – up from 8 to 12 per cent – after a scheme for extra female-only seats was introduced by the IIT Council in 2018.

IIT Bombay’s Patankar recalls looking around at her undergraduate biology class of 150 students and seeing “maybe three women” 10 years ago. Today, they make up 15 to 20 per cent of the course. “Just teaching that class makes me feel a lot better. It’s not enough, but I think that’s a really big change,” she says.

Female faculty numbers are improving, too, albeit slowly. According to information gathered for the Gender Advancement for Transforming Institutions project at IIT Delhi, women make up 37 per cent of PhD students at the university and 13 per cent of faculty, but the latter proportion falls below 10 per cent in STEM disciplines. And while women’s representation has improved at IITs, the environment for them could be better, reflects Aghalayam, who will become the first woman to lead an IIT when she takes over as inaugural director of IIT Madras in Zanzibar, the first overseas IIT branch campus.

“I wish I could say that although we’re small in number, we’re nurtured,” she says. “While I think we don’t have some of the very stark problems that other institutions have with bias…we do still have a few problems in terms of inclusion, being welcomed into spaces and leadership positions.”

In what are still heavily male-dominated institutions, women must sometimes adapt themselves to be heard, says Patankar. As a female professor, she has found ways of doing this, from power dressing to occasionally cracking down on student antics.

“From time to time, I have to remind them that I’m in control of the class. I have to step back from being friendly, and show I mean it,” she says.

Having more women in teaching positions makes a significant contribution to addressing the gender gap in India’s still largely traditional society, in which girls are encouraged to stay closer to home and to prioritise marriage and motherhood, says Kaur. “Where there are more women faculty, there is a comfort level for students. Also, the PhD years are a time when Indian women are being pushed towards marriage and motherhood, so how do you make those negotiations with families?” she asks, adding that female faculty mentors can be “crucial” in helping young women make career and personal choices.

Diversity in the classroom is another issue that IITs are still grappling with. Inevitably, some students – often those from poorer, more rural and lower caste backgrounds – fall behind. While many “may have been the best in their schools”, they are now competing against the cream of the crop from across the nation, including students with more resources and, often, better English, says Kaur. Unfortunately, it is often “the people who need help most” who are “the least likely to seek it out”.

Of the 2,461 IIT students who dropped out in 2018 and 2019, for instance, just under half were from reserved categories, and Education Ministry data revealed in 2021 that almost 63 per cent of undergraduate dropouts at the top seven IITs over the previous five years were from reserved categories.

When students of “significantly different” backgrounds and preparation levels are put into the university environment, many “can’t cope with the pressure”, agrees Rao, the former IIT Delhi director.

IITs have financial issues of their own. Although government cuts have not hit IITs as hard as other universities, they are ongoing – with institutions stretched ever more thinly in the race to cater to more students and attract top researchers. The problem is hard to ignore at many IITs, where gleaming new laboratories stand alongside crumbling legacy infrastructure.

“Labs decay because there’s no money for maintenance,” says IIT Bombay’s Mehra. “The government puts in 100 demands before they give you one rupee.”

Moreover, an influx of students has put more pressure on IITs to build more accommodation, adds Patankar. “Eventually we’ll have enough hostels, but it’ll happen after students have come in. That is something we’re all struggling with – we cannot keep up with infrastructure demands,” she says.

Rao says that the bigger problem is the lack of a financial model for expansion. Restricted in their ability to raise student fees by the government, yet pressed to beef up infrastructure and research, IITs have their hands tied, he says: “If we increase the fees, the media will pounce on us saying education is unaffordable. The government don’t allow that, but, also, they don’t give us more money.”

Currently, IITs’ funding is calculated based mostly on salary and pension liabilities, with a “little bit” extra for campus upkeep – a sum that’s barely enough “for sustenance”, let alone expansion, according to Rao.

In practice, this means missed opportunities. When he ran IIT Delhi, for example, Rao was unable to develop land given to the institution by the state government: “They gave us 100 acres of land, but then expected us to build everything. Seventy per cent of that land is lying vacant.”

But even as IITs face difficulties developing on their own campuses, they’re looking to branch out. Recently, under the National Education Policy, IITs – arguably India’s best higher education brand abroad – have been encouraged to develop their international ambitions, with IIT Madras in Zanzibar set to be closely followed by IIT Delhi in Abu Dhabi.

Already, some of these institutions have laid the groundwork for foreign branches. One such example is IIT Bombay’s research academy developed together with Monash University, in Australia, which Patankar headed for four years. In the decade since it was established, more than 200 PhD graduates have been through the academy.

The partnership was likely the first of its kind, according to Patankar (subsequently, IIT Delhi set up a similar collaboration with the University of Sydney). It is run by faculty members at both institutions; PhD students admitted into the programme spend at least a year at each institution and receive a graduation certificate with the logos of both. But while Indian students have clearly shown enthusiasm, the same cannot be said of their Australian counterparts.

“We always want the Australian students to come to IIT Bombay. We want a two-way street and it’s not happening,” says Patankar. “I’d love to see many organic collaborations and international students…It’s not enough.”

Recalling her stint as dean for international relations from 2018 to 2021, she notes that there were between 100 and 150 international students “at any given time” at IIT Bombay, a “minuscule” portion compared with its 10,000 domestic learners (including postgraduates).

While exchange students would come from countries such as Germany and France, many degree students funded by Indian government-backed scholarships came from outside the West, from countries such as Iran, Egypt and Bangladesh.

“I think it’s a matter of the perceived value of the IIT degree,” she says. “Our neighbours in South Asia see the value”, while Westerners are warier.

IITs are also wary of Westerners – unless they are among the top academic achievers. For instance, when Rao was leading IIT Delhi, “We did not want two different channels of admission, one of which was easier,” he says. Lowering the bar for overseas undergraduates would be grossly unfair “when we’re rejecting 99 out of 100 students in India”.

Instead, Rao sought to get more overseas students to do doctorates in India, creating 500 fully funded fellowships; nearly 100 students currently benefit from the programme. Elsewhere in the IIT network, too, the increase in international students is largely concentrated at the master’s and PhD levels.

Soon, though, IITs may find they have more competition. The federal government has issued a framework to help overseas institutions establish branch campuses in India in a move meant to tackle the country’s high demand for higher education. These universities will have carte blanche to set up shop in India and a great degree of autonomy.

One former IIT head, who asks to remain anonymous, is concerned over potential ramifications. The overseas campuses will be able to “admit whoever they want, pay whatever they want. I think that’s not a level playing field…These institutions will start poaching good faculty from IITs,” he says. “IITs will need to look at their entire model of admissions and faculty recruitment…if they want to compete with these foreign universities.”

And while the scholar is confident that IITs will continue to attract top talents, he is conscious that any lessening of their allure could have serious consequences because the “strength” of IITs ultimately resides in their researchers.

“Once faculty start leaving,” he says, “I don’t think there’ll be anything left of IITs.”

Brain gain: How can the IITs better serve India?

The Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs) are India’s pride. The popularity and success of the five IITs built in the first two decades of India’s independence – at Kharagpur (1951), Bombay (1958), Madras (1959), Kanpur (1959) and Delhi (1961) – led the Indian government subsequently to build many more of them.

IIT graduates are an enormous asset for the country. They have done very well for themselves too, both in India and abroad. The list of high achievers includes Ola Cabs co-founder Bhavish Aggarwal, IBM chair and CEO Arvind Krishna, Infosys co-founder and chair Nandan Nilekani and Google CEO Sundar Pichai.

Still, questions are sometimes raised about whether the IITs are doing what they were set up to do – to, as Nehru put it, “provide scientists and technologists of the highest calibre…to help [in] building the nation towards self-reliance in her technological needs”.

Brain drain is one issue. Over the decades, thousands of IIT graduates have migrated to the West for graduate studies and work. Most do not return. They have arguably benefited the recipient countries, especially the US, much more than India. A recent paper found that 36 per cent of the top 1,000 scorers in the 2010 IIT Joint Entrance Exams (JEE) migrated abroad after graduation – rising to 62 per cent among the top 100.

However, migration means that India benefits from huge remittances from abroad. Moreover, in recent years, even as the number of young Indians heading abroad has continued to increase, fewer IIT graduates are reported to have migrated. Many are finding well-paid jobs with global companies that have set up offices in India.

What has not changed is that large numbers of IIT graduates opt for non-engineering careers, such as finance, marketing and trading, usually after obtaining an MBA.

This is not surprising in an aspirational society. Many young people go to IITs because of their brand; there are few comparable undergraduate institutions that assure good employment prospects. A big chunk of young people who seek IIT engineering degrees do so because these are perceived to be helpful in obtaining lucrative non-engineering jobs in the corporate sector. In contrast, jobs in most branches of engineering – with the exception of computer science and electrical engineering – are not considered to offer desirable salaries.

In a recent interview, V. Kamakoti, director of IIT Madras, expressed concern about the supply of civil and aerospace engineers given the growing numbers of infrastructure and aviation projects in India. He called the flow of IIT graduates into non-engineering careers a “waste of resources” – and while not everyone agrees, his opinion is far from isolated.

Still, it is difficult to see what the government can do about it. There are only a handful of institutions that offer high-quality bachelor’s degrees in business and management, so it is unlikely that IIT aspirants who are not interested in engineering careers could be nudged to study these disciplines instead – unless, perhaps, the government were to build a dozen or more high-profile Indian Institutes of Business (IIBs) along the lines of the IITs. Or the IITs themselves could do the same; a few already offer good MBA programmes.

More broadly, however, India needs to bring about broader improvements in the quality of undergraduate education, so that at least 100 institutions become as desirable to students as the IITs. That is not likely to happen quickly.

Pushkar is director of the International Centre, Goa, and a member of the Academic Council at J.K. Lakshmipat University (JKLU).