Lesser-known Tuscany: sunshine on a plate

Oh, La Dolce Vita! How I craved it during lockdown and throughout the pandemic.

Ever since I met my husband, we’ve gone to Tuscany at least once a year – it is our home away from home.

We got married in Montecatini’s city hall, saying sì in the comune. We had our post-wedding aperitivo on the funicular cable car, which you can take to visit Montecatini Alto, the medieval upper town above the elegant spa. And we had our wedding party on the hilltop overlooking the Valdinievole valley.

From there, in other years, we have enjoyed seeing the firework displays of every town and village on New Year’s Eve. Verdi – yes, that Verdi – was of the opinion that these were the most beautiful views he had ever seen, and there’s a plaque to say so. No doubt he’d also love stumbling across operas and open-air concerts, as we have done on other trips to Montecatini, most memorably the one given by the celebrated Australian pianist David Helfgott.

We’ve enjoyed discovering Tuscany at different times of the year, and, while of course we’ve been to Pisa, Siena and Florence, we like to find the lesser-known places if we can.

We stay at an agriturismo, which is accommodation in a farm or farmhouse. In our case, it is self-catering accommodation midway between Florence and Pisa, at a farm above Monsummano called Podere San Martino. As it’s up a hill, it is washed over with cooling breezes at the height of the summer. It’s delightful to sit out in the morning with an espresso, and look through the silvery olive leaves to the views beyond and below, or in the evening with an aperitivo, listening to a local radio station that plays mostly opera. We usually take a pile of books, and after a visit to the local supermarket for some antipasti, you could easily just hole up there and read, relax and eat. But there’s plenty to do if you are inclined.

Vinci, the birthplace of Leonardo, is well worth a visit. Go for lunch and take in the museums of his drawings and inventions. There’s a photo opportunity, of course, next to a sculpture based on the Vitruvian Man with a terrific backdrop. For food, we try to go where the Italians go. There’s a good restaurant with a vine canopy to sit under, and we usually have what we’ve nicknamed “sunshine pizza” – a margherita pizza, but unlike any UK margherita pizza; it really does look and taste like someone brought you sunshine on a plate.

Another favourite day trip is to the medieval walled town of Lucca. It is pedestrianised in the centre so you can wander around the cobbled streets and soak up the Italian vibe, stop for a coffee, or have lunch. You might, as we did, stumble on the botanical gardens. Puccini was born in Lucca, so if you want some culture you can visit his house, which is now a museum. It is also worth visiting one or two of the 100 deliciously crumbly churches that Lucca is home to. Most people take a walk or cycle around the ramparts, but you can even take that easy by renting an electric bicycle!

And if you really want to live the Italian life, try going in November and helping with the olive harvest. We did it one year, laying down the netting, coaxing the olives off the trees, gathering them up and taking them to the cooperative, where we saw them turned into olive oil. If you’ve never had a meal smothered in emerald-green new olive oil, shared with the pickers, pressers and bottlers, you haven’t lived.

Harriet Dunbar-Morris is dean of learning and teaching, and reader in higher education, at the University of Portsmouth.

The Panama Canal: enrichment between the seas

Captain Jeremy stood up and introduced himself to the hundreds of assembled passengers on the Miami-to-San-Diego “enrichment” cruise, most of whom were American retirees.

“I’m English,” he announced. “That means I’m not the one with the funny accent. You are.”

The audience chuckled – at least, those who understood his accent. I was one of several dozen speakers, workshop leaders, musicians, naturalists, spiritual gurus and others assigned the task of enriching these grey-hairs as we cruised from the Atlantic to Pacific oceans via the Panama Canal. Three short talks over a 16-day trip: it was a working vacation, with the emphasis on vacation.

I always liked boats. My first job teaching university undergraduates was as third mate on a schooner; I taught them navigation and how to tie knots. I had also worked as a passenger boat captain in Boston and a deckhand on windjammers in the Caribbean.

The MV Explorer was a lot more comfortable. There’s the swimming pool – try to get your daughter out of it. There’s a couple of bars – try to get your brother-in-law out of them to look after the kid in the pool, as he’s supposed to be doing.

But let’s talk culture. There were lectures on regional history, music and architecture. We learned about the ring of Spanish fortresses in the Caribbean built to protect its trade in slaves and precious metals, among other imperial interests. Your correspondent taught a class on Mexican drug cartels. The best lecturers (not your correspondent) were great storytellers, simply narrating images on a screen. Other contributors gave sessions on fiction writing, Tai Chi and Spanish language (your correspondent’s wife).

Into yoga? Try the “balancing table pose” while pitching and rolling at sea. Thinking about self-improvement? Try the workshop by a thirtysomething on “how to overcome my inhibitions and achieve all I can achieve”. Except, as a successful retired person, you might wonder what the point is.

Some talks edged into the paranormal, like the one called “how to awaken within my dream while I’m still dreaming.” (And then what, you might ask.) There was little sleeping during classes, though; most of the students were switched-on and continued asking lots of questions even days after the presentation was over. Lectures became ongoing conversations around the ship, and subjects of contemplation as you watched the dolphins, whales and flying fish.

But the biggest topic of conversation was the young passenger who returned late from shore leave in Cartagena, Colombia. Outside the harbour, the ship pulled to a halt and, being a boat guy, my instinct told me something was wrong. I went up to the top deck, from where I could see the bridge. Officers were watching the harbour through binoculars, and after about an hour, a fast boat sped out with the delinquent. His mood was described later by the crew as not simply chastened but “over-stimulated”. This being Colombia, he was asked whether he had procured anything illegal while ashore, at which point he was relieved of about three grammes of cocaine.

The fate of the lad was in the hands of Captain Jeremy, who decided that he should be put ashore in Panama. The cost to the plank-walker: about $1,500 for the extra fuel (because we had a specific canal entry time and now had to accelerate), plus his short-notice plane ticket home. The benefit – he wasn’t handed over to the Colombian police.

Finally came The Path Between the Seas, as David McCullough titled his 1977 tale of the Panama Canal’s construction. A steel drum band on the pool deck. A row of barbecue grills churning out ribs and burgers. Canal workers smiling and waving. Canals are where the maritime and the land worlds converge.

We passed through locks with inches to spare, steaming slowly through neighbourhoods and past jungle-covered islands in Lake Gatún. We saw the remnants of the original Panama railroad, completed in 1855 (almost 60 years before the canal) by my ancestor, William Henry Aspinwall, a 19th-century New York tycoon; neither expense ($8 million) nor lives (5,000 plus) were spared in its construction. And we steamed past El Renacer, the prison that housed former strongman Manuel Noriega, arrested in 1989 by invading American troops.

The navigation precautions in the canal are astounding – buoys every few yards along its 77 kilometres, range lights, sector lights, radar reflectors: it almost seems as if Homer Simpson could pilot a ship through here. Captain Jeremy did the job flawlessly, while a former canal pilot narrated – in an American accent.

I had been on deck all day by the time, early evening, we reached the Pacific coast exit, the lights of Panama City twinkling off to the port side. I was hot, sunburned and thirsty. But if I had been captain, I’d have turned the ship around and gone through the canal again.

Mark Aspinwall is a research professor in the Division of International Studies at the Centre for Research and Teaching in Economics (CIDE), Mexico City, and affiliated professor at the Centre for Contemporary Latin American Studies at the University of Edinburgh.

Australian writing retreats: crocodile cheers

For a country where something is always out to kill you, Australia has been remarkably cautious in relation to Covid. Our borders have been closed largely since March 2020, when I raced home from England just in time to avoid hotel quarantine. As a result, many Aussies, including me, have been rediscovering local holiday destinations.

This might be controversial, but I hate Sydney. For a mid-sized city, it is stupidly loud. Having the airport in the middle has only one advantage: it is only a short trip from it to the coastal walk to Bondi (the city’s only good bit). There, you can recover from your 18-hour flight. Then go somewhere better.

As a historian based at a Sydney university, I have generally sought to escape the city to write. One favourite retreat is Airlie Beach, in northern Queensland. You’ll be lucky to find a spot as idyllic as my uncle’s dining table, overlooking the ocean towards the Whitsunday islands, but there are plenty of other places to write – or not. And there is lots to do when you’ve finished (or failed to start). A life highlight remains snorkelling with fish that looked like Nemo’s school friends, in an underwater landscape of brightly coloured coral.

I’ve mainly visited the area in the Australian summer, but that comes with special risks. There are crocodiles, though following local instructions still leaves plenty of great places to swim. It is the tiny, deadly Irukandji jellyfish washing in on the summer tides that you really have to watch out for. A jellyfish-proof wetsuit known as a stinger suit is a wise investment.

Queensland’s summer is also monsoonal. I happen to love hot, sweaty, humid days with frequent downpours of what seems half the sky. Cyclones are a little scarier, though cyclone parties compensate: once everyone has stocked up on bottled water and taped up the windows, they all get together to drink unless the cyclone is large enough to demand evacuation. Really, Queenslanders are crazy – but mostly in a good way.

Winters are much more civilised, though. In July, north Queensland sits at a comfortable, usually dry 20-odd degrees. The water is tepid rather than bath-warm, and the Irukandji are on holiday somewhere else.

An alternative writing retreat is Seven Mile Beach at Gerroa, just south of Sydney. This stunning, very long beach has relatively small waves that rarely dump children, so it is a favourite site for surf schools. The area is so safe that endangered birds happily sit on their nests on the white-golden sands as the children play around them. I used to write from a beach shack with a view, though camping by the croc-free river is also stunning.

A few hours inland from Sydney, Orange and nearby Mudgee are ex-gold rush foodie towns in a stunningly beautiful wine growing region. The TV series The Heart Guy was filmed there. The peaceful bush is distinctly Australian but is not harsh enough to be “outback”. Beautiful in summer, it tends to be cold in July – all the better to enjoy good food and red wine.

Trains and buses run from Sydney, but a car will give the best access to wine and food growers. There are plenty of places to stay – check out the gorgeous loft above Cargo Road Winery. On our last visit, we stayed in a pub in town, ending our day singing and dancing with a Pacific Islander crew who had just finished a job in the local gold mine.

My final writing retreat destination is on the way from Sydney to Orange and is so great that I have moved there permanently. The Blue Mountains are a Unesco World Heritage-listed national park containing a series of villages with a thriving local music scene. The area also has its share of dangers, though I have only seen one snake. And the crisp, clean air, amazing birdlife and beautiful walks – from long hikes to short rambles – make it an infinitely preferable place to live than the noisy, polluted metropolis a two-hour train trip away.

Hannah Forsyth is senior lecturer in history at the Australian Catholic University.

Lyme Regis: fossilised thinking

I have long wanted to be considered slightly mysterious and even a little exotic. This desire probably reflects the fact that, in reality, I’m about as exotic as a roast potato. Sadly, I appreciate that my choice of holiday destination will only reinforce this assessment.

I tried to build a case for Barbados, Western Australia, Hawaii, Kenya or the Greek islands, but my sentences rang hollow. I was fooling nobody, least of all myself. So now for the brutal truth: my most missed holiday destination during lockdown was Lyme Regis.

The British seaside occupies a special place in my heart. It evokes multiple childhood memories of the sea, sandcastles, ice cream, fish and chips, pink sunburned bodies, and the freedom to roam and explore boundaries, both geological and personal. Lyme Regis, known as the “Pearl of Dorset”, is a particularly wonderful example.

After the outbreak of the French Revolutionary Wars at the end of the 18th century, England’s upper crust could no longer travel to mainland Europe. Lyme, with its elegant Georgian architecture, filled the gap. Jane Austen and her family holidayed there in 1803 and 1804, inspiring her novel Persuasion. Then, in 1969, Lyme resident John Fowles published The French Lieutenant's Woman, filmed 12 years later in Lyme and starring Meryl Streep. More visitors and films have followed.

But it was Lyme’s location on the Jurassic Coast World Heritage Site that particularly inspired my initial interest. My first trip there was at the age of 16, on an A-level geology field-trip. I had been fascinated by fossils throughout my childhood, and this was like entering another world, stuffed with ammonites, belemnites and ichthyosaur vertebrae. The sheer thrill of finding such fossils remains one of my most consolidated adolescent memories.

I have been back countless times since, for a variety of reasons. Of course, for multiple family holidays. I have vivid recollections of our children, impervious to the bracing temperature, demanding ice cream – and then, a bit older, learning to sail Laser dinghies, insensible to the commands of “slow down” as they raced into the harbour completely exhilarated. Most recently, we have gathered as adults for New Year’s Eve around a fire-pit with fish and chips, waiting for the fireworks.

I frequently “hide” in Lyme, too, to write a grant, paper or prepare a talk. I have fooled myself that I can only really think deeply when I am in Lyme, following a long walk. Maybe it’s the maritime atmosphere or the calm, or perhaps the bacon sandwiches and fresh coffee from the bakery – who knows? But I need it.

Before Covid-19, my wife and I would frequently pop down to recharge. The glorious walk through the Site of Special Scientific Interest known as the Undercliff to the village of Axmouth feels like walking through a fern-filled lost world. During spring, the woodland is carpeted with bluebells and wild garlic.

Winter is also a very special time in Lyme, especially when the great waves crash over the harbour wall, known as the “Cobb”. The sheer energy is awesome.

I usually make a pilgrimage to St Michael's Church and the grave of the great palaeontologist Mary Anning. Among her various monumental finds was the first complete skeleton of a Plesiosaurus in 1823. The fossil was so odd it was considered a fake by the French “father of palaeontology” Georges Cuvier. But after much debate (in which Mary was not invited to participate, of course) the Geological Society of London declared it genuine, and Cuvier apologised. Fellow pilgrims to Mary’s grave often leave fossils collected from the beach, and children occasionally leave small plastic dinosaurs. Mary’s finds changed our view of the world, but she died in poverty from breast cancer in 1847 at the age of only 47. An excellent statue, capturing her energy, was recently unveiled in Lyme honouring her contribution to science.

So Lyme, for me, is all about happy memories, natural beauty, fossils, the smell of the ocean and the cry of gulls. But it is also about the comfort of familiarity and, not least, the ease of getting there – about a three-hour drive or train journey from where I live.

Airports featured large in my pre-Covid life, and I tolerated the experience of queuing, being frisked, removing clothing, worrying about my carbon footprint, and being exposed to the palpable pheromonal smell of unease – or something more sulphurous – from my fellow travellers. I have moved on. Today, my inner cry is: “No more this airport hell, I’m off to glorious Lyme Regis!”

Russell Foster is director of the Sleep and Circadian Neuroscience Institute at the University of Oxford. His new book, Life Time: The New Science of the Body Clock, and How It Can Revolutionize Your Sleep and Health, was published on 19 May by Penguin.

Ravenna: Dantean Paradiso

Summer after summer, my feet repeatedly land in Italy. But of all the memories I’ve gathered from those trips, one in particular stands out. And it was in a city that many tourists overlook.

Ravenna, in northeast Italy, is a treasure trove of east-west history, art and culture. From AD 402 until 476, it was the capital of the Western Roman Empire and then the western capital of the Byzantine Empire until it was captured by the Lombards in 751. It is best known for its monuments and churches, dating from the 5th and 6th centuries. Eight are designated Unesco World Heritage sites for their dazzling early Christian mosaics.

Vespers in the Basilica of San Vitale, with its lofty dome covered in spectacular glass designs and set on an octagonal base, is a mystical experience. Just across the courtyard, the Mausoleum of Galla Placida offers a glittering iconography in vivid shades of blue and gold, representing the victory of eternal life over death.

An added draw is the annual Ravenna Festival of music, dance and theatre, presented in venues and public spaces throughout the city, including some of the World Heritage sites.

Topping it all off, Ravenna offers the world famous cuisine of the Emilia-Romagna region, including the Michelin-listed Osteria del Tempo Perso, along with noteworthy hotels like the lovely Albergo Cappello. Inviting pedestrian walkways allow for an after-dinner stroll to the beautiful Piazza del Populo, built by the Venetians in the 15th century.

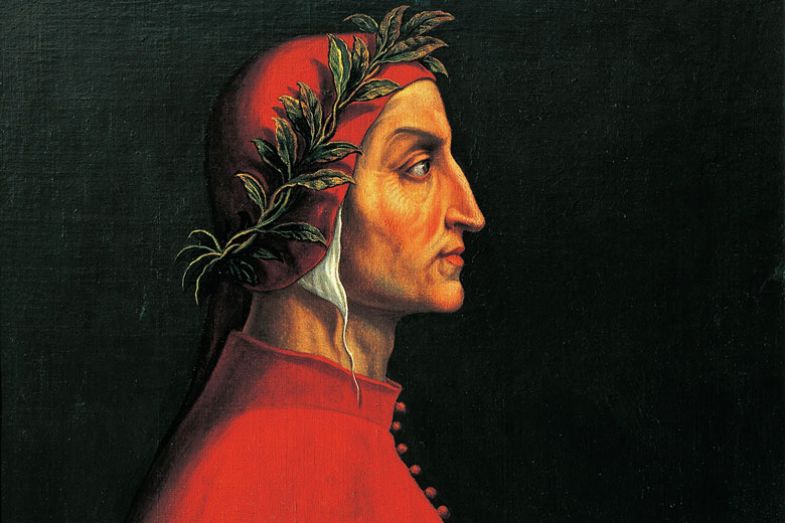

Less well known are Ravenna’s many points of reference to Dante Alighieri, the medieval poet, moral philosopher and father of modern Italian. The story of how Dante, born in 1265 in Florence, was banished from his native city and ultimately died in exile in Ravenna has all the intrigue of a political thriller. But the epic poem he completed in the city, La Divina Commedia, is on another plane entirely. His visionary trip through the heaven, purgatory and hell of the Christian afterlife is considered one of the greatest contributions to Western literature. Hence, despite repeated attempts by Florence to wrest his bones as his fame grew, Ravenna has jealously guarded them for 700 years – even in the face of a papal edict.

Although I had visited Ravenna in the past, I returned with a mission in the summer of 2017. I was working on a book project on “the rise of English” and its global impact on opportunity and identity. The topic inevitably led me to Dante’s works, some written in Latin and others in Tuscan, for an apt quote or insight on the power of the vernacular in the face of a dominant lingua franca.

I found myself in front of Dante’s tomb, joining with 100 local cittadini (citizens) in a “call and response” recitation of verses from “Inferno”, the first of La Divina Commedia’s three cantiche, powerfully led by two “callers” dressed totally in white. From the tomb, we processed through the streets to the sounds of a haunting drumbeat, ending at the Teatro Raso for a live enactment of the “Inferno”, with full audience participation.

I can still feel my heart pounding and my hands clutching my husband’s arm as we wove with Dante, guided by the Roman poet Virgil, from one dimly lit room to another through the circles of hell, encountering an assortment of sinners, until we emerged from the darkness into the starlit skies of Ravenna. Little did I know what the next few years would bring or how I would look to Dante for clarity and comfort as I pushed to complete my manuscript through the darkness of the pandemic.

The book, now published, recounts my Divina Commedia experience with the cittadini of Ravenna and reflects on how it “made palpable the enduring force of language in defining a community”. And although the pandemic kept me from visiting Ravenna in 2021 to celebrate the 700th anniversary of Dante’s death, my days of walking in his footsteps have not ended – either figuratively, through his writings, or literally, through the city in which he wrote his timeless work.

Rosemary Salomone is Kenneth Wang professor of law at St John’s University – New York. Her book, The Rise of English: Global Politics and the Power of Language, is published by Oxford University Press.

St Andrews: Busy doing nothing

St Andrews might seem to be a strange holiday destination for an academic. Few of us play golf – the game’s endlessly frustrating pursuit of a pointless goal is too reminiscent of university bureaucracy to be enjoyable. And there’s very little else for a visitor to do or see in this remote three-street town on Scotland’s windswept east coast.

The tourist sites consist of the 12th-century cathedral (in ruins), a small castle (in ruins), and St Rules Tower – climbing its narrow 156 steps allows you to survey the town and confirm that there is nothing else for you to visit.

But that is the key to its appeal. Spared from the development that mars many tourist destinations, St Andrews remains breathtakingly beautiful. If you’re lucky with the weather, when you crest the hill that overlooks the town as you approach from Leuchars (the nearest train station, five miles away), you will be greeted by a Leslie Hunter landscape. Brilliant yellow fields of rapeseed slope towards the town, with the dark blue of the North Sea beyond and then the lighter blue of the sky, the town’s low, honey-coloured skyline punctuated only by the spires and towers that proclaim its ecclesiastical past.

To the north-west lie the West Sands, two miles of golden beach that was the location of the evocative opening moments of the film Chariots of Fire. Eastward lie the picturesque harbour and pier, and then another long, curving beach with quiet breakers rolling in from the sea.

St Andrews’ lack of tourist attractions is liberating. As faculty at the local university, Scotland’s oldest, will attest, academic work never ends. There are always more articles to read, papers to write, meetings to attend, classes to prepare. You quickly become habituated into thinking that you must always make productive use of your time – and feel guilty if you don’t. This habit is hard to break. Hence, choosing a destination with a wealth of attractions could result in a holiday marred by the worry that you’re not making the best use of your time, that you haven’t seen everything you should.

St Andrews has none of this pressure. You’re not going to miss anything. You can simply relax. Browse the used bookshop Bouquiniste at the cobbled end of Market Street. Enjoy a leisurely ice cream from Jannetta’s (a fixture since 1908), an indulgent fudge doughnut from Fisher & Donaldson, or a long walk on the West Sands after a delicious fish supper. Watch the rotund seals roll in the bay and wonder how soon all those calories will lead you to resemble them.

St Andrews encourages self-reflection, being symbolically evocative of the life of the mind not just because of the university’s presence but because of its location, set apart from the world. Not that the intellectual life is unworldly: the ruination of the cathedral, the result of the Scottish Reformation, is a stark reminder of the potency of ideas. So too are the mine and counter mine below the castle’s walls, which date from its besieging after the Protestant reformer George Wishart was burned there for heresy in 1546.

These competing tunnels also remind us of the back and forth of academic debate – not least because the defensive mine only saw off its rival after two false starts and significant rerouteing. But while the mines were dug in haste, the ancient presence of the university, founded in 1413, reminds us that academia is a long game: we should resist the temptation of rapid publication to ensure that our contributions are worthwhile.

Beautiful, restful and evocative, St Andrews is the perfect place for recuperation, reflection and regirding, before returning to the academic fray.

James Stacey Taylor is a professor of philosophy at The College of New Jersey. His most recent book is Markets with Limits: How the commodification of academia derails debate.

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber?