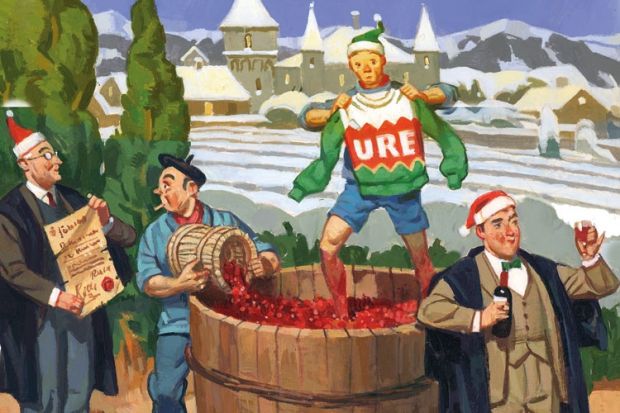

Source: Paul Slater

At a Christmas-themed lunch, the main course was an excellent venison dish (“from our own herd of Rudolphs”, contributed the v-c, pointing towards the deer park with a bloodied knife)

As the train eased into the elegant Victorian station on that crisp December morning, I admit that I was still having some concerns about my visit to the University of Rural England. The ten years that had passed since my first meeting with its famously pugilistic vice-chancellor had not dimmed the picture I still had of him: ranting, scarlet-faced, at a bewildered audience of academics at a seminar in darkest Bloomsbury. I was hoping that he had mellowed somewhat in the interim.

Within a quarter of an hour, a taxi had deposited me outside the sculpted sandstone edifice of the Old Abbey, at the heart of the URE estate. A smiling – and somehow familiar – member of staff directed me to reception, where I was met by the head of communications, and over a welcome cup of coffee she described the plan for the day.

First up was a visit to the newly refurbished library.

As we made our way through the corridors, quads and halls of the campus, I noticed a sense of focused calm in the people we passed. Around them the infrastructure was of impressively high quality and well maintained, with teams of workers tending the wintry gardens in the milky sunshine. The brightly coloured sweatshirts worn by cheerful students bore the prominent slogan, “URE: The Best University You’ve Never Heard Of”. The whole place exuded a sense of well-being – so much so that it was almost disturbing.

Tasteful glass and steel additions to the original structure, along with heady infusions of high technology, had turned the west wing of the Old Abbey into an exemplary modern workspace. As the head librarian handed me his business card, I asked him about the “URE 1000” logo embossed on it. “This year marks our 1,000th anniversary,” he smiled. I must have looked sceptical, because he elaborated: “The Abbey scriptorium was established in 1013 and – in an intellectual sense at least – that marks to me the foundation of the university.” I began to wonder what else my hurried research had failed to reveal about the place.

Lunch was served in the Senior Common Room. The view from it was charmingly bucolic; extending across the frosted lawns and meadows to the river, it sat well with the Tudor panelling, leather Chesterfields and massive stone fireplace of the room, which was tastefully decorated for the season. I decided I rather liked URE.

The vice-chancellor, glass in hand, met me at the window and introduced himself with a handshake of immense presence. Whether it was the effect of being on his home turf I don’t know, but he seemed relaxed – youthful even – and with the air of a country gentleman hosting an informal weekend house party. As we sat down to a Christmas-themed lunch, the main course of which was an excellent venison dish (“from our own herd of Rudolphs”, contributed the v-c, pointing towards the deer park with a bloodied knife), he declared that verbal combat could commence.

My first request was to discover the origin of the excellent claret – the first taste of which burst upon my jaded palate like nectar. The v-c smiled: “I’m glad you like it; we source it from our own estates. We are lucky enough to have retained – or, in a sense, rediscovered – our connections with some small family vintners in the region.” Rediscovered? “Yes, a lot of our legal records were thought lost in the great fire of 1802, and it has taken a while to resolve matters.”

Intrigued, I asked for details. The registrar, an astonishingly pale figure alongside the robust, claret-fuelled v-c, took up the tale. “It really stems from our Institutional Review in 2009. The economic meltdown was a disaster, so we commissioned a group of City experts to advise us and, while much of their advice was unpalatable, a few core elements did meet our needs.”

The v-c was more forthright. “He means that after those bloody Viking bankers waltzed off with all our cash, we were stuck firmly up shit creek. They told us to shed the crap and reel in the mass-market punters before we lost our shirts. Could you bung the wine over? Thanks awfully…”

So, I enquired, what did they decide?

“We don’t do mass market on campus – never have, never will – any more than we kowtow to government policy or hang on the results of every half-arsed survey that comes out. We know what we’re good at, and while I object to some sleazy-suited pimp telling me I need to ‘centre myself on core values’, I admit he had a point. So we chucked most of the courses you can get elsewhere and built up our specialisms.”

“I was pleased to see”, interjected the librarian, “that our work on medieval property law and document preservation got massively increased support. And the work we were subsequently able to do with the manuscript collection gave us truly astonishing insights into traditional herbology and our new work on environmental pharmacology…”

The v-c held up a warning hand the size of a shovel. The librarian subsided visibly and his domed forehead coloured.

“We’ll get to that – maybe…We’ll see…

“More importantly, the new work on ancient documents trawled up a load of assets that we didn’t know we had. Admittedly, a bunch of French farmers were pretty sour when they discovered they were tenants rather than owners, but as we’re now able to invest a decent wedge in their wineries I think they’ve forgiven us. A lot of the rest were random bits of wet meadow spread across the country – but it seemed that more than a few were being lined up to be turned into distribution centres and retail parks, so the value ended up being…well, astronomical! Cheers! More wine anyone?”

That certainly explained the excellent state of the infrastructure and the obvious investment in state-of-the-art technology – but what else had it enabled the university to do?

“First off,” said the v-c, easing his bulk into a sofa, “it allowed us to address one of our key targets – that of social disengagement.”

“Disengagement?” I asked, unable to conceal my surprise.

“Yes, we thought the whole government direction on engagement was flawed. Don’t get me wrong, we understand our obligations: we give some of the best scholarships and bursaries in the country, and to people who will really benefit. But handing out themed cupcakes to publicise some fatuous TV tie-in courses on 21st-century baked goods design? Sorry, that’s just embarrassing.”

So what form does the disengagement take? “Telling the government to stick their poisoned policies – and their dodgy money – where the sun doesn’t shine and doing what we’ve always done: use our graduates to represent us in the world – and to act as our source for the next generation of students and staff. You can’t get a place here through Ucas – try it, we aren’t even listed – it is by personal recommendation. We know what talent we want, and we’re prepared to go out and look for it – we even use our massive open online courses as bait.”

A collective sigh of despair issued from the senior management team.

“Now,” continued the v-c warningly, “I’m not saying we haven’t had problems – mostly due to that swine of a software developer ogling the director of teaching and learning when he should have been listening.”

“He confused Moocs with MMORPGs,” interjected the ogled party. “You know, massively multiplayer online role-playing games – those hack’n’slash computer games. And we didn’t spot it in time to scrap it and start again.”

“But as a result,” the v-c pressed on, “aside from picking out some excellent recruits, we have a massive new market sector to capitalise on. Thousands of smelly, nerdy gamers who get to slay the next zombie horde only once they have passed the assessment for the course module. I think it’s the future of HE revenue, to be perfectly honest, and I’m told that the rendering of medieval combat is beyond reproach. Even better, we never have to meet the geeky little buggers.”

Aren’t Moocs supposed to be free?

“Oh yes, the basic product is free, but if you want the upgraded weapons…” The v-c’s smile was oddly disconcerting.

“And I’ll tell you this,” he pointed a stout, quivering finger at me, “if any of your feeble REF-junkie mates are still having trouble with their top people being poached, we can certainly sell ’em a ‘nought point two’ who’ll train them in the tools they need to defend themselves.” His finger swung to the fireplace, above which a brace of broadswords hung as though ready for action.

Stunned, I tried to visualise the sorts of figures the v-c was referring to when he talked blithely of discarding government funding and initiatives. Surely it amounted to more than a few property deals and virtual crossbows?

The registrar nodded. “We have managed to gain a significant diversity across our income streams, which we consider guarantees our academic independence.”

Environmental pharmacology?

“That is certainly one element,” confirmed the registrar carefully, “but others are also very encouraging.”

Coffee and brandy were circulating by now, and flakes of snow began to fall beyond the mullioned windows. The brandy gave me the courage to press the v-c on this point. “We saw a market opportunity and believe it is something we are uniquely suited to delivering,” he responded. “We have begun to sell fellowships.”

I choked on my coffee. How, I asked, could that possibly be defensible?

“Easy. You see, URE is in a town full of decent country folk who mind their own business and don’t hold with others getting above themselves. We noted the number of prominent academics – and former academics – who were having a somewhat parabolic relationship with television. You know the folk I’m talking about: they get a series on BBC Four, make a decent job of it and get another couple on BBC Two – except they’ve already used up much of their specialist knowledge and have to work on the edge of their expertise. Before they know it they are wildly overexposed, the public gets bored with them and it is either the daytime game-show circuit or a bungalow in Bexhill.

“We offer an alternative: anonymity here at URE and doing some decent research again – they’ve really boosted our publications record – or a bit of light gardening if they’re too burned out.”

I recalled the figure who’d guided me to reception. “Was that…?”

“Yes, he loves it here. There was a time when he couldn’t walk down a London street in safety – here, no one gives a damn. We’re up to about fifty fellows now – and it’s a nice little earner I must say. They sometimes get a bit rowdy when their shows get repeated, but a bit of quiet lawnmowing usually does the trick.”

My time was up. Almost reluctantly, I said my goodbyes and the head of communications drove me back to the station. As we shook hands at the snowy platform entrance, she handed me a carrier bag with some brochures, a packed meal, a rather stylish URE T-shirt and a bottle of water. “The v-c asked me to say that he hopes to see you again soon,” she said with a beaming smile.

“I hope so, too. Merry Christmas!”

On the long, slow train journey back to London through the Stygian countryside, I reflected on the revelations of the day, unaware that another still awaited me. Exhausted, I unpacked the meal and as I drank the bottle of URE-branded spring water, I felt an extraordinary rush of calmness, sudden clarity of thought and an understanding of my place in the world. Shocked but elated, I examined the label with some care, but it gave no clue to its secret other than “Bottled at our own source”. I began wondering what the librarian had almost said about the new department of environmental pharmacology.

It was then that I found the letter of invitation from the vice-chancellor, and I realised that Christmas might be coming early this year.