Source: Alamy

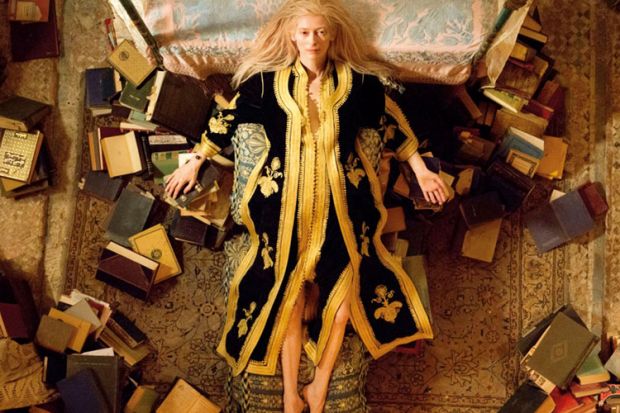

There will be more than blood: Eve and Adam inhabit a fetishistic world of objects, texts and instruments that make the vampiric life enviably worth living

Only Lovers Left Alive

Directed by Jim Jarmusch

Starring Tilda Swinton, Tom Hiddleston, Mia Wasikowska and John Hurt

On general release in the UK from 21 February

Being a vampire movie, there has to be blood, and never has its imbibing been more seductive

Jim Jarmusch wants us to know that vampires have really great taste. Adam and Eve, the couple at the beatless heart of Only Lovers Left Alive, have spent centuries rubbing shoulders with the great and the innovative in the worlds of literature, art, music and science. Adam’s wall is adorned with photographs of Oscar Wilde, Christopher Marlowe, Buster Keaton and Joe Strummer. But, as he keeps repeating, “he has no heroes”: it is the vampires who are the creators. Adam gave his adagio to Schubert to pass off as his own, just as the work of Marlowe (himself a vampire) was willingly attributed to the “illiterate zombie philistine” Shakespeare.

“Zombie” is the term these vampires use to describe humans, and the neat conceit here is that the vampires would draw too much attention to themselves if they published under their own names. They allow inferior zombies to pass off the work as their own, so that the vampires can keep to their shadowy liminal lives and stay undetected by society, under the radar. Their motivation is to “get the work out there”.

The red Gothic lettering of the film’s credits evokes traditions of Hammer Horror, but this addition to cinematic vampire lore is a radical departure into a fetishistic world of objects, texts and instruments that make the vampiric life enviably worth living. The film begins with the tactile drop and crackle of a record starting up on a turntable, and as the 45 spins the camera swoons in circles around Eve and Adam in their respective homes. Eve’s is a boudoir in Tangier, full of net curtains around a four-poster bed, piles of books and candles. Adam’s den is a teenage muso’s wet dream, stashed full of drum kits, guitars, amps and mixing desks, located in music’s Mecca, the now desolate Detroit.

Adam and Eve are married vampires, and have been in love for centuries. Adam’s depressed state brings Eve to the rescue, travelling at night, first class, impeccably dressed and carrying only steel cases of books she apparently cannot be without. As they greet each other with an intense physical connection but the language of courtly love, the unique parameters of their marriage become clearer. Eve looks at a photograph of them in wedding attire and whispers, “June 23rd 1868, our third wedding”: they have lived and loved across centuries and their relationship is realistically poised between the intensity of ardent lovers and the mundaneness of a long-married couple.

Adam’s depression, it emerges, is based on the zombies and their – our – treatment of the world. Seeing us as ruled by fear, dry of innovation and skill, Adam feels that “all the sand’s at the bottom of the hourglass”. For Eve, however, a self-professed survivor, this self-obsession is “a waste of living”, when Adam could be appreciating nature, nurturing kindness and friendships, “and dancing”. These exchanges get to the heart of this peculiarly reassuring film. Adam and Eve are cultured aesthetes, with a sense of bafflement and isolation that makes it easy to identify with them as outsiders in a foreign city, physically vulnerable bodies, and then as irritated but indulgent relatives of a wayward teenager.

They take on this last role when Eve’s little sister, Ava, comes into their calm, cultured enclave like an electrifying explosion. Playing her as a flirtatious, petulant and dangerous teenager, Mia Wasikowska sets fire to the ashen Adam and the translucent Eve, exposing tensions between the two and dragging them down from their high-culture perches to the indulgent messiness of the teen-vamp and her tastes.

As Eve, Tilda Swinton retreads her steps from Sally Potter’s Orlando (1992) as she crosses centuries and continents. This time, however, she is not searching for her identity but sampling the riches that each era has to offer. Here is a vampire who relishes life, both its long-term continuities and its fresh incarnations, and takes the long view on how the world works. Detroit, she says, will rise again because it is a city that has water.

Tom Hiddleston is a convincingly bloodless Adam, all self-important recluse and precious artiste. While no match for Swinton in terms of physicality or screen presence, his pinched features and Brit-boy enunciation serve the vampire-as-tortured-artist well, and enable Swinton’s magisterial aura to envelope and nurture him, and convince us that she has done so for centuries…

Jarmusch has chosen to make these vampires our avatars of good taste and lifestyle aspiration. As Eve assembles her travelling books she scans them with her eyes and fingers, devouring every image, character and letter. As she lowers the needle on the 45 of Charlie Feathers’ Can’t Hardly Stand It, those riffing chord changes sound like the pinnacle of musical achievement. As Adam executes scales on his violin, strums the strings on his 1905 Gibson or caresses the wooden bullet he has commissioned for the suicide he toys with, his exquisite sensory and intellectual acumen is enviably realised.

Being a vampire movie, there has to be blood, and never has its imbibing been more seductive. In today’s world, coming by blood from the necks of humans is no longer an option owing to contamination and risks to health. So keeping their supply and nutrition up to speed has become a job in itself. Getting samples from corruptible hospital workers appears to be the favourite method, and Jeffrey Wright is perfectly pitched as an edgy but cheeky haematologist who keeps Adam supplied with O negative.

Once safely home, the dark syrupy nourishment is decanted into delicate little sherry glasses; when sipped, it induces a state of euphoria conveyed in the same cinematic way as Renton and Sick Boy’s post-heroin hit in Danny Boyle’s Trainspotting (1996). The vampire drinkers sink back into their cushions, ecstasy drawn across their faces, bloody residue clinging to their lips and fanged teeth.

Techniques for getting the bloody hit are updated, however, as Ava swills from her hip flask and Eve produces bloody ice popsicles from the freezer that Adam thought did not work. (It does: Eve just plugged it in.) These charming domestic details sit peculiarly well alongside the fetishistic aesthetic that Jarmusch has created to convey the allure and isolation of his lovers’ lives. Unsurprisingly from a director who made a feature film about people’s smoking and caffeine habits, Coffee and Cigarettes (2003), paraphernalia and ritual feature heavily, markers of coolness and style as pronounced as the carefully contrived soundtrack. As Swinton strides in slow motion through the backstreets of Tangier, chalk-coloured from her hair to her boots, and Hiddleston reclines bare-chested and all in black, the film’s style is self-consciously pre-eminent.

The literary and cultural allusions can jar and distract in the way they are forced into the dialogue, unless one surrenders oneself entirely to this playful fable and accepts its aim as conveying the need to embrace the cosmos in all its beauty in order to endure. Eve observes that red-spotted fungi are emerging at the wrong time of year and tells them that they are too early. The idea that the world and what matters in it have a very long history and an uncertain future is hardly original, but the notion that vampires have the cultural high ground as a result of their longevity is a fresh take on a genre that has recently become the fodder of the teen movie in the Twilight books and films.

Jarmusch also exploits the humorous possibilities of his protagonists’ longevity when John Hurt as Marlowe responds to Eve’s criticism of his weskit that he was given it in 1586 and it really is one of his favourite garments. It is reassuring to hear from Adam that Byron was a pompous ass, but at the very last knockings Jarmusch delivers the money shot that the previous two hours have only flirted with. Adam and Eve may be shown to be the bloodthirsty vampires they are, but this film will undoubtedly compel you to put on a record, pick up a book and sip a strong sweet sherry from a very fine glass.