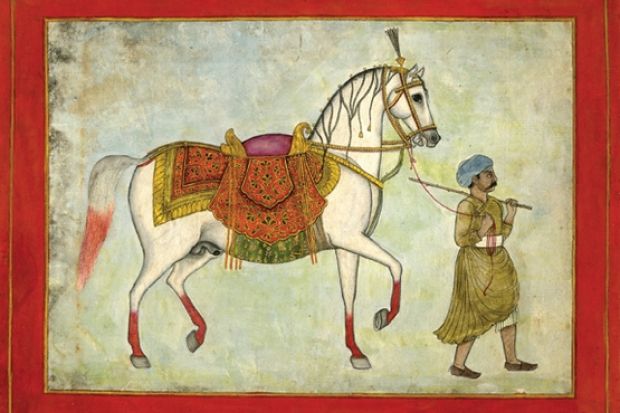

Credit: Album Leaf/A Horse with Elaborate Saddle and Harness Being Led by a Groom

The Horse: From Arabia to Royal Ascot

British Museum, London, until 30 September

When I read that this exhibition would focus on two breeds - the Arab and the thoroughbred - I thought it would struggle to also show “the epic story of the horse” over 5,000 years. However, curators John Curtis and Nigel Tallis have used the Diamond Jubilee and the Olympics to draw out threads in that story. The iconic image of the monarch on horseback and the popularity of modern equestrian sport waymark their thematic journey from the ancient Near East to contemporary Britain.

The exhibition includes objects from the British Museum and other notable collections. Although many are on permanent display and some are familiar from books, when gathered together their impact is considerable. Even the most finely produced images cannot fully capture the shimmer in the gypsum wall plaques from Assyria or the contrast between the blue lapis lazuli, cream shell and red limestone on the Standard of Ur. The array of severe bits from early Luristan takes on a clear context when they lead the way to a full-size model of an armoured Islamic horse and warrior.

The curators have chosen simple but highly effective methods to connect cultures and ideas. A beautifully illustrated 14th-century horsemanship manuscript is positioned so that a large painting by George Stubbs of a famous racehorse and his jockey (Gimcrack with John Pratt up on Newmarket Heath, 1765) can be seen through a window into the next room. If you stand alongside that painting and look back through the window, you see the life-size armoured horse and warrior again. The links between war, hunting and sport on horseback in the lives of the elite resonate throughout the exhibits.

Much of what is on display reveals how influences work across time and space. The 19th-century chalk drawings of the Parthenon’s Head of the Horse of Selene by Benjamin Robert Haydon are positioned alongside original objects from the 10th to 5th centuries BC. The work of contemporary artists Afsoon and Jila Peacock, inspired by the traditions of Iran and Turkey, is positioned close to 16th-century Safavid watercolours of the legend of the Persian hero Rustam. The European style of a tinted ink drawing of a Persian cavalryman, aimed at pleasing the demand for souvenirs by 17th-century visitors, recalls the relationship between the horses of the Arab world and the Europeans who desired their speed, grace and stamina.

The 17th- and 18th-century Mughal miniature paintings were the highlight of the exhibition for me. Alongside their delicacy, fine detail and rich yet subtle colours, the touches of wit and naturalism are charming. My particular favourite was A horse with elaborate saddle and harness being led by a groom, a simple image of a grey stallion, his tail and legs decorated with henna, following his handler with relaxed energy. The shared focus, looped lead rope and unused switch resting casually over the groom’s shoulder are laden with information about quiet leadership and confidence between horse and handler.

Horses across the collection share features such as stylised arched necks and unnaturally long backs, accentuated characteristics that reflect the nature of the rider or desirable qualities in the horse. This is typified in several paintings of oddly proportioned 18th-century racehorses, which retain the physical extension of the gallop even at a standstill.

The Anatomy of the Horse by George Stubbs, by contrast, offers a slightly disturbing reminder that few other images in the exhibition make any attempt to get under the horse’s skin.

Around its central themes, the exhibition also finds room for some quirky byways, such as the focus on Wilfrid Scawen Blunt and Lady Anne Blunt. The self-romanticising of these 19th-century travellers, as well as their importance in establishing the pure-bred Arab horse outside its native lands, hints at the personal passions that can drive the horse enthusiast. This is welcome alongside the strong element of propaganda that runs through many of the exhibits.

The use of interactive features and film helps to link the horse as a living creature with fine art eternalising moments that would last seconds in real time. While the galloping or leaping horse is an elegant but remote image, the chaotic horse-and-carriage traffic jam in a Pathe newsreel of early 20th-century Manchester is a reminder that everyday travel depended on the horse not so long ago.

With the development of the thoroughbred from three Arabian horses in the 18th century, the story of racing ties the loose threads together. While a great spectator sport, racing reinforces messages about prestige and power and brings people together in a way that accentuates their divisions. Curator Tallis points out that, in William Powell Frith’s The Derby Day (1856-58): “All life is here - at the racecourse.” The joke, of course, is that the crowded painting makes the horses incidental to the posturing, gambling, flirting, gorging and starving that is happening on the sidelines as they race.

Horses return to the foreground, though, in the final exhibit, a short film that captures the power, strain and energy of the modern racetrack as the “epic story” hurtles into the future.

This exhibition is likely to appeal as much to schoolchildren and families as to academics and enthusiasts and also to inspire various responses. I left my horses at home and made a long journey by train to see images of horses instead, and the exhibition highlights the irony of this. Through art and history, we see the great importance of the horse in world culture, yet those artefacts and records distance us from it. When Tallis took members of the exhibition team to film the semi-wild ponies of the New Forest, some were disappointed by what they saw. The image of the gleaming horse galloping across the horizon with the wind in its mane is as distant from the muddy animal mooching around a field as airbrushed photos of supermodels are from people on the street.

The curators are clearly aware of the discrepancy between the real horse and the horse as presented in the exhibits, and hope to offer “something to reflect on about our interaction with the natural world”. The overall dynamic of the exhibition, though, is that the horse is a resource to be used, shaped, romanticised and coerced. Few of the exhibits show it as anything other than an expression of human ingenuity or power. Yet when talking to the public about the events surrounding the exhibition, Tallis was repeatedly asked, “Will there be real horses?” This desire to connect with a large, potentially dangerous, but naturally amenable animal, offers a more positive interaction with the natural world. It is also a well-documented aspect of the story of humans and horses that is noticeably absent in this collection.

However, while I would have liked to have seen some acknowledgement that there are other ways to view the horse rather than simply as a resource, this is an excellent exhibition and worth visiting. It is also at the centre of a series of linked events, including Horse Power Day on 30 June, when there will be real horses on site. I suspect that the opportunity to see them will make that the busiest day of the run.