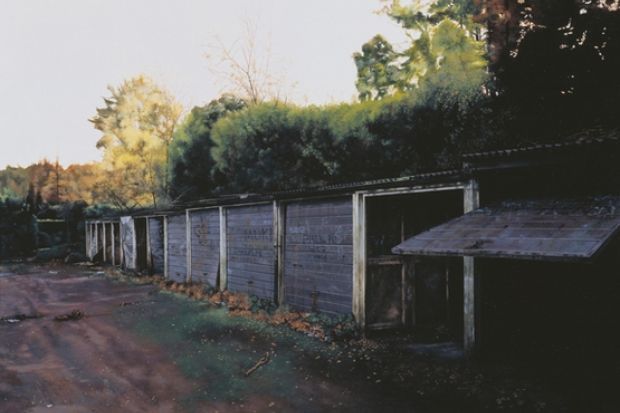

Credit: Scenes from the Passion, late 2002/George Shaw

Thresholds

Tate Liverpool, until 7 April 2013

From the moment statute formally divided the Tate from the National Gallery in 1954, the Tate collection has had a difficult relationship with segregation. Where do Turner and Constable belong? Was Impressionism historical or modern? How do we define the borders of “British art”? These dilemmas were dress rehearsals for similar questions posed by the division of Tate Modern and Tate Britain in 2000.

The Liverpool Biennial opened on Saturday, and with it Tate’s contribution: Thresholds, a medium-sized exhibition on the second floor of Tate Liverpool that addresses such taxonomic distinctions. Beyond its official Biennial context, the show also has institutional echoes, more recent as well as historical. It recalls themes explored earlier this year in Tate Britain’s Migrations: Journeys into British Art, which used the collection to consider the international ebb and flow of influences in British art over the past 500 years. It also occasionally evokes the mood and aesthetic of Patrick Keiller’s The Robinson Institute, currently at Tate Britain, another collection-based foray into the Britain behind British art. Across these shows emerges a powerful and slightly melancholy sense of the fungibility of a national identity and a reminder of the problematic nature of a national collection.

Where Migrations was principally historical, Thresholds has a more contemporary remit and a sharper theoretical focus on the notion of the border itself. Exhibitions with such a pronounced theme run certain risks: artists’ works can quickly become connecting clauses in curators’ arguments, illustrative rather than interesting in their own right. The Robinson Institute used a fictionalised curator (Robinson) to neutralise this difficulty; rather than being concealed, the construction of the display was made emphatic and theatrical. Thresholds eschews the problem more directly, both through the weight of its content and the aesthetic interest that permeates the exhibition. Themes and arguments, although prominent, avoid subsuming the artist’s voice - literally so, given a film of interviews with the exhibited artists early in the show.

Among the exhibition’s many highlights is Hurvin Anderson’s Jersey (2008), displayed in the first room. This is one of his Peter’s Series, large paintings depicting barbershops housed in domestic spaces where public and private slip into one another, just as the spaces he constructs dissolve into abstraction and flashes of colour. The more abstract, schematic character of his painting is punctuated by depictions of a human trace, in this case the flecks of hair that remain on the barbershop floor.

Anderson shares a wall with an elegiac painting of a row of garages by George Shaw, Scenes from the Passion (2002), where human absence is similarly conspicuous. Shaw’s sense of absence is all-pervasive; the people are gone and the paintings’ own surfaces have an impersonal, photographic sheen.

Further down the wall is Mark Wallinger’s Half Brother (Exit to Nowhere-Machiavellian) (1994-95), a large oil painting of a horse in profile, divided vertically. Strictly speaking, the horse is united vertically, as the front and the back belong to different racehorses (their names being Exit to Nowhere and Machiavellian). Wallinger’s horse-halves offer a metaphor for the overall hang, describing the careful matching-up of work, the nuances simple associations can provoke, and something of the show’s wit - for all its seriousness and subtlety, the thought of a pantomime horse is never far away when looking at Wallinger’s painting. This first room is given the title “Stranger than the Self”, itself strange because it seems to address thresholds that are primarily spatial rather than psychological. Anderson’s public/private space, Shaw’s town/country suburb and Wallinger’s man-made/natural horse are also united in their reflections on man’s relationship with the environment.

This peculiar engagement with nature is seen again in Keith Arnatt’s series A.O.N.B. (Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty) (1982-84), photographs that subvert the idea of the picturesque by pointing the camera in another direction. The artist visited officially designated beauty spots but looked at them askance, to explore “the conjunction of ‘beauty’ and ‘banality’”. The photographs’ subjects become banal human interventions in the landscape: roadside cafes, signposts, refuse, kerbs and fences. The ghost of Tintern Abbey lurks in the background of one, setting up poetic resonances between the abbey’s mutability and the more immediate and modern transience of the images’ everyday subjects. The photographs are of thresholds, and also perhaps from thresholds, as they capture a disconnect between the anticipated experience and the actuality of a British day out.

If the focus of the first room is British, the remaining rooms - titled “Shifting Boundaries” and “Territories in the Making” - have a more international emphasis (although, given that the show repeatedly undermines the concept of nationhood, one hesitates to use the word). Yukinori Yanagi’s Pacific (1996), a large grid of Perspex boxes, contains national flags depicted in coloured sands, with tubes connecting the grid. The artist released ants into these tubes, and as the ants marched across the flags they disrupted their patterns and shapes.

Elsewhere nationhood comes in the form of maps and is treated similarly violently. In United Kingdom (1999), Layla Curtis cut up and reassembled a road map of England in the shape of Scotland and vice versa, dividing the two countries and setting them alongside one another. Made in the year the Scottish Parliament first convened, United Kingdom is a wry comment on devolution (except that the maps’ subversion stops on the coastline, so the thorny issue of North Sea oil is omitted). Nevertheless, like Yanagi’s Pacific, Curtis’ work seems politically timely. To consider notions of the nation state and hospitality in the weeks after the threatened deportation of students from London Metropolitan University is a valuable cultural contribution.

The Liverpool Biennial is titled The Unexpected Guest. Coupled with Thresholds, these thematic interests might be read as indications of biennial self-awareness. Could these titles be comments on the ubiquitous biennials themselves, events notable for the improbable and brief appearance of an art crowd, where the internationalist promise of difference is so often dampened by a troubling sameness?

In the second room of the exhibition, Sophie Calle’s The Hotel project documents the 12 rooms she cleaned during three weeks spent working as a chambermaid in a Venetian hotel in 1981. These voyeuristic vignettes of unknown guests are extremely intimate but at the same time oppressively anonymous, and her responses to the blank visitors range from fond affection to indifference. The Hotel series raises troubling questions about tourism and engagement with a local environment that could easily be shared by a self-reflective visitor to the Biennial.

Thresholds is an accommodating subject that could have been taken in any number of directions. Those pursued by Tate Liverpool are well chosen: sufficiently various to do the theme justice and to allow a broad church of artistic practice but sufficiently interconnected to give the exhibition a satisfying unity. And there is of course something particularly powerful about situating this exhibition in Liverpool. According to a plaque beside a new, bizarrely socialist-realist bronze on the docks’ waterfront, some 9 million emigrants passed through Liverpool on their way to the New World. Even if this show is not about the Biennial, it is certainly, to some extent, about Liverpool, once Britain’s paradigmatic threshold city.